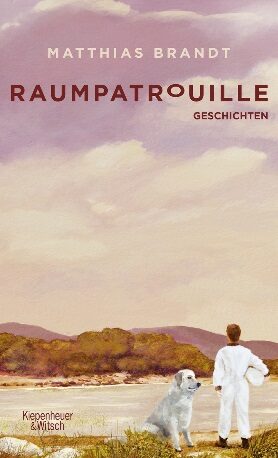

Matthias Brandt

Raumpatrouille

[Space Patrol]

- Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag

- Cologne 2016

- ISBN 978-3-462-04567-3

- 176 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

A Desire for Normality

A story hardly worth telling or spectacular in any way if the father under discussion didn’t happen to be the chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany at the time. The boy’s name is Matthias, the father’s Willy Brandt. In 2006, Lars Brandt, Matthias’s ten-year-older brother, published "Andenken" ["Momento", unavailable in English], a charming little book filled with snatches of memory from his childhood. And now, when reading Matthias Brandt’s "Space Patrol", the sense one already had of an enormous disconnect only intensifies: There’s Brandt the politician and later recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, the personification of an open, liberal country. And, as is perhaps only natural, there’s the absent father, ever distant and oddly lost in thought.

Growing up under such exceptional circumstances is precisely what stirs in the eight- or nine-year-old Matthias (born in 1961) a deep desire for normality. The title itself, "Space Patrol", is a reference to the exploration of the universe and the new, unchartered dimensions of the make believe brought about by the first moon landing. This little book bursts with nostalgic potential. The accoutrements and zeitgeist of the former German republic are captured in passing, as it were, by the child’s observations. At the same time, however, what really takes place in "Space Patrol" is what always happens when the challenges of narrating from a child’s perspective are successfully overcome: the pure, innocent viewpoint manages to expose, illuminate, and reveal in an almost frightening way, thereby peeling back the official images that have anchored themselves in the collective memory of an entire nation.

In one especially funny chapter, for example, Matthias is designated to go on a bike ride with his father and a colleague of his, one Mr. Wehner, following their ongoing professional differences. The adventure was conceived as the ideal setting for an official reconciliation. The boy has never seen his father on a bike before, and, in fact, an extra bicycle must first be obtained. Yet the outing ends after only a few minutes when his father crashes. Cursing, Brandt abandons his bike, lights a cigarette, and walks back to his house, leaving the dumbfounded Mr. Wehner at the side of the road and his son to continue the ride all by himself. "I should have taken better care of him," he still tells himself. This book has its share of unreciprocated affection. That and a young boy’s instinctive protest against outer constraints, against the police and guards permanently installed on their property, and against the embarrassing fact that while all other fathers have a driver’s license, his own is always being driven around by a chauffeur.

When the young Matthias sleeps over at a friend’s house one night, he is overcome with joy at partaking in a completely normal family evening - dinner together, TV in jogging suits - until he becomes terribly homesick at night. Such ambivalence lurks everywhere in "Space Patrol", which recounts the story of a privileged, sheltered childhood - and one that is just as empty and lonely.

Translated by Franklin Bolsillo Mares

By Christoph Schröder

Christoph Schröder, born in 1973, works as a freelance author and critic for Deutschlandfunk, Die Zeit and Süddeutsche Zeitung among other media outlets.

Publisher's Summary

The stories in Matthias Brandt’s first book are literary journeys in a cosmos familiar to us all – the cosmos of childhood – examined with a very particular eye here.

In this case, it’s a childhood in the ‘70s of the last century in a small city on the Rhine River, which was the capital of West Germany at the time. A childhood populated by a sometimes snappy dog called Gabor, by Mr. Vianden, mysterious postmen, fearful nuns, religion teachers disabled in the war and nice Mr. Lübke from next door, who serves hot chocolate and is starting to run out of things to say. There’s his father’s odd work colleague, Mr. Wehner; a custodian; and even a chauffeur, since dad happens to be the Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Brandt writes about complicated bike outings, heavily guarded trips to fairs, monstrous soccer defeats, bizarre doctors’ appointments and about passions that burn out as quickly as they flare up – for stamp collecting, for example. Last but not least, we read about parents as shrouded in secrecy as they are loved, and about a childhood filled not only with adventure and imposture but also with fantasy, danger and loneliness. An unforgettable book.

(Text: Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag)