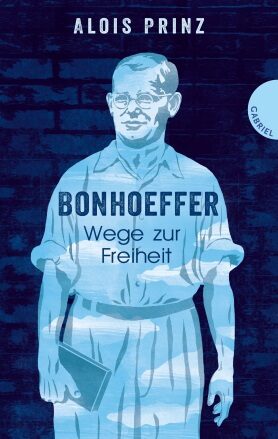

Alois Prinz

Bonhoeffer. Wege zur Freiheit

[Bonhoeffer. Paths to Freedom]

- Thienemann-Esslinger Verlag

- Stuttgart 2017

- ISBN 978-3-522-30455-9

- 272 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

The Middleman of God

It is hardly surprising that the distinguished biographer Alois Prinz chose Bonhoeffer as the hero of his most recent work. Among the myriad texts Prinz has written thus far, several of his biographies focus on the extraordinary personalities of Christianity. Prinz portrays the mystic Theresa of Avila as vividly as the apostle Paul and Francis of Assisi founder of the Franciscan order. From the start, he lays bare his affinity for the respective luminaries whose lives he is depicting, yet notably resists the perils of idealizing them.

The Bonhoeffer book, “Paths to Freedom,” also is distinguished by this special feature. Prinz's impressive portrayal of the execution in Flossenbürg on the final pages is preceded by a layered description of the character and intellectual development of the theologian: Bonhoeffer - born in 1906 to a bourgeois family in Wroclaw and raised in Berlin as the sixth of eight children – displayed from an early age an unusual talent in a wide variety of disciplines. He could have enjoyed as good a career as an athlete as he would have as a pianist. His decision to study theology, of all things, barely impressed his father, the famous neurologist Karl Bonhoeffer. Despite his success in academia, the young Dietrich Bonhoeffer decided a university career was not for him. Instead, he wanted to be a priest.

According to Prinz, after spending several months in New York in 1930, Bonhoeffer realized his true calling was to serve mankind: while there he had spent time in the African American communities in Harlem. He discovered in the gospel songs and electrifying style of the preachers a completely new and worldly form of Christianity. When he returned to Germany, he not only was a committed pacifist, but also highly sensitive to the political and social upheavals of the time.

Prinz brings to life Bonhoeffer’s personality in all its complexity and contradictions. With his penchant for music, elegant clothing and extended journeys, at times he appears to be a typical dandy of the Weimar Republic. That said, he often behaved rather awkwardly towards women, although he wanted nothing more than a companion for life. He exuded resolve and confidence on the outside - even if, or especially when crises of faith and meaning raged from within.

From early childhood, Bonhoeffer had considered it his duty to be a role model for others and, regardless the circumstances, he always kept himself under control. But did this automatically make him a heroic resistance fighter? Without moralizing, Prinz reminds his readers that even the strongest characters are not immune to acting against their conscience: In April 1933 - the Nazis had recently seized power - the Jewish father-in-law of Bonhoeffer's twin sister Sabine had died. The family wanted Dietrich to hold the funeral. But Bonhoeffer's superior advised against “burying a Jew during these times.” Bonhoeffer followed this advice. A short time later he regretted his decision and begged his sister’s forgiveness for having been a coward. Even though she forgave him, he couldn't forgive himself.

From then on, Bonhoeffer spoke tirelessly against the injustice of the despots. He printed flyers and travelled abroad to warn of the imminent danger of war waged by Germany. Soon his teaching license was revoked and later he was banned from speaking publicly and writing, but he didn't let it intimidate him. Prinz illustrates in scrupulous detail and compellingly the crucial role Bonhoeffer played in the “Church Struggle”. The theologian was by far the most fearless representative of the “Confessing Church,” and was a staunch opponent of the anti-Semitism of the “German Christians,” who were united under Hitler.

In 1939, Bonhoeffer returned to the USA, where he was offered a position as professor in Harlem and a comparatively low-risk existence as an exile. This time however, his conscience triumphed over the need for security. After four weeks, Bonhoeffer boarded a steamer back to Nazi Germany, where he began working for the “Amt für Abwehr” under the direction of Wilhelm Canaris. Officially, he was now in the service of the National Socialists, unofficially he was active as the middleman of God, supporting those who agreed with him that an assassination attempt on Hitler was the only remaining solution.

Bonhoeffer’s above-mentioned poem, “By gracious powers so wonderfully sheltered,” had been enclosed in a letter he wrote to his fiancée Maria von Wedemeyer at Christmas in 1944 from the prison in Berlin-Tegel. According to Prinz, Bonhoeffer had believed he would soon be liberated and finally would be able to start the life he had been dreaming of for so long with his 18-year-younger bride.

When the secret records of the also imprisoned Wilhelm Canaris were found shortly thereafter, and Hitler learned what extent the “Office of Defense” was involved in plans to assassinate him, Bonhoeffer's fate was sealed. But even in the face of certain death, he lost nothing of his cheerful composure. Prinz mainly bases his information on the reports of contemporary eyewitnesses, but fortunately does not try to give a psychological explanation of Bonhoeffer's seemingly superhuman equanimity. Thus ends the description of the human being, of Dietrich Bonhoeffer as he had lived and with a bow to the hero when he died.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

By Marianna Lieder

Marianna Lieder works as a freelance journalist and literary critic for publications including the Tagesspiegel, the Stuttgarter Zeitung and Literaturen. She has been an editor at Philosophie Magazin since 2011.

Publisher's Summary

Dietrich Bonhoeffer stands as no other for the courage to stand up for one's convictions, political involvement, pacifism and altruism - regardless of religion and social class and across all national borders. He lived what he preached, took a clear stand. Thus he became an important role model for young and old. Alois Prinz has set out on the tracks of this man who, in spite of his clearly defined stance, was torn between self-confidence and self-doubt and who never ceased seeking his place in the world. It is precisely this life-long quest that makes Bonhoeffer into such a powerful figure of identification in equal measure for both youngsters and adults.

(Text: Thienemann-Esslinger Verlag)