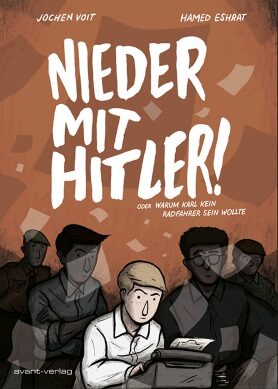

Jochen VoitHamed Eshrat

Nieder mit Hitler! oder warum Karl kein Radfahrer sein wollte

[Down with Hitler! Or why Karl didn’t want to be a bullying brownnose]

- avant Verlag

- Berlin 2018

- ISBN 978-3-945-03498-9

- 152 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Jochen Voit

Nieder mit Hitler! oder warum Karl kein Radfahrer sein wollte

[Down with Hitler! Or why Karl didn’t want to be a bullying brownnose]

Greek rights already sold

Sample translations

When injustice becomes the law. The story of a Nazi-era youth resistance group in graphic-novel form

Historian Jochen Voit and cartoonist Hamed Eshrat put the lives of five Nazi-period youngsters in the spotlight in an unusual and interesting fashion in their graphic novel ‘Nieder mit Hitler! Oder warum Karl kein Radfahrer sein wollte’ (‘Radfahrer’ is used here not in its literal sense, ‘cyclist’, but in its slang sense of ‘someone who bows down to those above while stamping hard on those below’).

There are of course already various comic books and graphic novels that deal persuasively with the Nazi period, starting with Art Spiegelman’s Maus. However, this story by Voit and Eshrat, focusing on the experiences of five youngsters in the Thuringian town of Erfurt, departs from the usual pattern of graphic novels, based as it is on the actual life story and reminiscences of the now 91-year-old protestant priest Karl Metzner. As a pupil at the local Handelsschule (business-oriented secondary school) in the 1940s he met Jochen Bock, a factory owner’s son. Following the death of his beloved elder brother on the Eastern Front in 1942 - perhaps even earlier than that - Jochen became a dedicated opponent of Nazism and a keen advocate of democratic and humanistic ideals. He and Karl, who came from a social-democrat family, became soul-mates. They secretly listened to foreign radio stations - even this seemingly minor offence attracted extreme penalties. Together with three other schoolmates they started a resistance group in 1943, typing out and distributing leaflets with wording borrowed from the antifascist organisation ‘Nationalkomitee Freies Deutschland’ (‘National committee for a free Germany’). Denounced soon afterwards by other pupils at their school, they were arrested by the Gestapo and charged with high treason. They escaped the much-feared death penalty not least because their form teacher - a Nazi Party member - wrote them good character references. Karl was released after eight and a half months in prison.

The tragic irony of the story is that as a priest in the socialist German Democratic Republic Karl Metzner once again attracted the baleful attention of state security forces. Attempts were made to blackmail him into acting as a spy on church affairs, and following the failure of these attempts he once again became an ‘enemy of the state’. He was one of the founders of the independent Peace Movement, and in 1989 played an important part in the Peaceful Revolution that led to the demise of the GDR. In the final pages of the novel - which recounts the events of the Nazi and GDR periods from Karl’s own vantage point - there is an illustration showing him in his priest’s garb as one amongst a mass of people demonstrating for the introduction of democracy. The illustration is dominated by a banner the wording of which also serves as the story’s leitmotif: ‘When injustice becomes the law, resistance becomes a duty’.

Jochen Voit and Hamed Eshrat are not out to propound this tenet as a categorical imperative neatly extracted from Karl’s first-person account of the brave deeds of the five schoolboys. Instead, they use the everyday experience of youngsters growing up in a dictatorship to show how difficult it is - not to say lethally dangerous - to seek in such circumstances to maintain one’s own integrity and to deal openly with others on the basis of truth and fellow-feeling. Aided by Eshrat’s perfectly judged illustrations, Voit powerfully demonstrates the dire consequences faced by individualists such as Jochen and Karl, no matter how naive and spontaneous their opposition to injustice happened to be.

In the case of young people not particularly inclined to read conventional books, the classic genre of the graphic novel might well prove wonderfully effective in opening their eyes and encouraging them to engage more closely with contemporary history, to see it from the perspective of real individuals, and to draw comparisons with their own life. This is especially likely when narrative and illustrations combine to bring the dramatic sequence of events as vividly to life as this book succeeds in doing with its compelling dialogue and the thrilling shifts of perspective accomplished in the drawings.

Translated by John Reddick

By Siggi Seuß

Siggi Seuß, freelance journalist, radio script writer and translator, has been writing reviews of books for children and young people for many years.

Publisher's Summary

Suddenly Karl remembers everything. The summer of 1943. The frustration over the German defeat at Stalingrad. And the death-defying idea of overthrowing Hitler. Karl and his school friends distribute leaflets against the Nazis, are arrested and imprisoned by the Gestapo. With luck they escape the death penalty.

That was almost 20 years ago. The teenager Karl has grown into an adult. As a pastor he takes care of a small parish in the GDR. He rarely thinks about those days. Until the day he goes to Berlin and meets up with a member of the Stasi, who confronts him with a difficult decision...

The graphic novel Nieder mit Hitler! tells his story for the first time.

(Text: avant Verlag)