Mathias JeschkeKatja Gehrmann

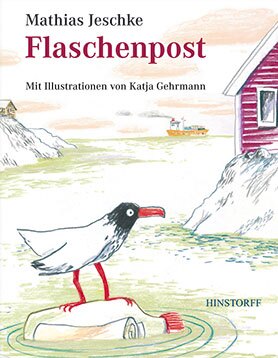

Flaschenpost

[Message in a bottle]

- Hinstorff Verlag

- Rostock 2009

- ISBN 978-3-356-01295-8

- 32 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Mathias Jeschke

Flaschenpost

[Message in a bottle]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Spanish: Argentina (2009 - 2011).

Sample translations

Review

To entrust a message to the caprices of the elements, whether it be rolled up and attached to a balloon or sealed inside a bottle, invariably means offering a challenge to Chance: who, if anyone, is going to find the message? Where are they going to find it? Will it ever even arrive anywhere? And if so, how long will it take? In Mathias Jeschke’s picture book Flaschenpost(‘Message in a bottle’), it takes a whole eleven years for one such message to find a recipient: a nine-year-old boy who lives on an island north of the Arctic Circle and happens to find it on a beach.

Mathias Jeschke recounts this not exactly everyday tale as if it were a true story: ‘I took the the bottle and threw it overboard. It was pure high spirits: I wasn’t in distress or sitting on some lonely island waiting to be rescued. An epic journey began right then and there.’ The story is told in language that is simple yet never one-dimensional, terse yet always friendly and approachable. Furthermore, there are rarely more than two or three sentences per page. This pared-down narrative mode works like a kind of spark firing the reader’s own thoughts and imaginative processes.

Precisely such an effect must have been experienced by Katja Gehrmann, the illustrator. Her illustrations show just how deeply she entered into the spirit of the text. At numerous points her drawings convincingly develop the story beyond the sheer words, indeed towards the end of the book the pictorial strand takes over as the main vehicle of the narrative, with the result that we learn more from looking at the pictures than we would have done from merely reading the words. We see how the narrator packs his rucksack, boards a plane, and arrives on the little island of Bolga where Marius, the boy who found his message, is waiting for him. The successful interplay of word and image shows just how perfectly this duo of Katja Gehrmann and Mathias Jeschke are in tune with each other — no wonder, then, that Flaschenpost is their second project together.

Whereas in their previous joint venture Gehrmann decided on large, powerful images, she opts this time for a finer line and for the more restrained colouration of crayon. At the same time she leaves plenty of room for expanses of white. In conjunction with the sea — which is present in almost all the drawings, sometimes depicted as calm by the use of light blue shading, sometimes as a raging maelstrom with blackish-blue wave-crests — these expanses of white form the backdrop to skilfully created splashes of colour. The predominant tones here are the reds of pullovers, hats and scarves, and also of houses and boats — which stand out even more clearly as a result. In this way a particularly lovely effect is created in all the drawings; the whole atmosphere conjures up the clear air of a day by the sea, with the kind of light that occurs only along the far northern coastline.

Just as Jeschke’s narrative mode offers plenty of scope to the reader’s imagination, so too do Gehrmann’s illustrations. The spare language of the text is matched by her restrained use of her crayons, whereby she often limits herself to bare outlines. Thus for instance we see a harbour, wooden houses, fishing boats entering and leaving, a couple of people waving — but the boats and the harbour buildings aren’t fully drawn, much as the story itself is hinted at rather than spelt out.

We also encounter another lovely idea in this book: complex or unfamiliar terms from the nautical world are explained in brief notes, accompanied by vignette-like illustrations, that are readily comprehensible to children as well as adults. Topics covered by these explanations include Morse code, the way outboard motors work, and the question of how left and right, front and back are designated on a boat: ‘The sharp end of a boat is called the bow; the bit at the back is the stern. The right-hand side is starboard; the left-hand side is port. It’s easy to remember: “Star light, star bright, starboard to the right”, and “the ship left port”.’

But this children’s book is not just about left and right, it is also about yesterday and today: quite long spans of time are summoned up in the young reader’s imagination in a wonderfully sensitive way. The fact that the bottle and its message were cast into the sea before its finder, Marius, was even born brings home to young readers inclined to identify with him that other things existed before they did — and thus the past is rendered palpable. Whilst this might conceivably have given quite a jolt to a child’s sense of time, any such effect is neutralised by the sense of continuity that is deliberately generated at the visual level: just as in the first illustration the narrator is sitting in a rowing boat — as a young child with his grandfather — so too at the end of the story he is again sitting in a boat (albeit one with an outboard motor) — as an adult with young Marius, the finder of the message. The bottle may have drifted all alone for years in the cold North Sea, but in the end it serves to bring people together.

Mathias Jeschke recounts this not exactly everyday tale as if it were a true story: ‘I took the the bottle and threw it overboard. It was pure high spirits: I wasn’t in distress or sitting on some lonely island waiting to be rescued. An epic journey began right then and there.’ The story is told in language that is simple yet never one-dimensional, terse yet always friendly and approachable. Furthermore, there are rarely more than two or three sentences per page. This pared-down narrative mode works like a kind of spark firing the reader’s own thoughts and imaginative processes.

Precisely such an effect must have been experienced by Katja Gehrmann, the illustrator. Her illustrations show just how deeply she entered into the spirit of the text. At numerous points her drawings convincingly develop the story beyond the sheer words, indeed towards the end of the book the pictorial strand takes over as the main vehicle of the narrative, with the result that we learn more from looking at the pictures than we would have done from merely reading the words. We see how the narrator packs his rucksack, boards a plane, and arrives on the little island of Bolga where Marius, the boy who found his message, is waiting for him. The successful interplay of word and image shows just how perfectly this duo of Katja Gehrmann and Mathias Jeschke are in tune with each other — no wonder, then, that Flaschenpost is their second project together.

Whereas in their previous joint venture Gehrmann decided on large, powerful images, she opts this time for a finer line and for the more restrained colouration of crayon. At the same time she leaves plenty of room for expanses of white. In conjunction with the sea — which is present in almost all the drawings, sometimes depicted as calm by the use of light blue shading, sometimes as a raging maelstrom with blackish-blue wave-crests — these expanses of white form the backdrop to skilfully created splashes of colour. The predominant tones here are the reds of pullovers, hats and scarves, and also of houses and boats — which stand out even more clearly as a result. In this way a particularly lovely effect is created in all the drawings; the whole atmosphere conjures up the clear air of a day by the sea, with the kind of light that occurs only along the far northern coastline.

Just as Jeschke’s narrative mode offers plenty of scope to the reader’s imagination, so too do Gehrmann’s illustrations. The spare language of the text is matched by her restrained use of her crayons, whereby she often limits herself to bare outlines. Thus for instance we see a harbour, wooden houses, fishing boats entering and leaving, a couple of people waving — but the boats and the harbour buildings aren’t fully drawn, much as the story itself is hinted at rather than spelt out.

We also encounter another lovely idea in this book: complex or unfamiliar terms from the nautical world are explained in brief notes, accompanied by vignette-like illustrations, that are readily comprehensible to children as well as adults. Topics covered by these explanations include Morse code, the way outboard motors work, and the question of how left and right, front and back are designated on a boat: ‘The sharp end of a boat is called the bow; the bit at the back is the stern. The right-hand side is starboard; the left-hand side is port. It’s easy to remember: “Star light, star bright, starboard to the right”, and “the ship left port”.’

But this children’s book is not just about left and right, it is also about yesterday and today: quite long spans of time are summoned up in the young reader’s imagination in a wonderfully sensitive way. The fact that the bottle and its message were cast into the sea before its finder, Marius, was even born brings home to young readers inclined to identify with him that other things existed before they did — and thus the past is rendered palpable. Whilst this might conceivably have given quite a jolt to a child’s sense of time, any such effect is neutralised by the sense of continuity that is deliberately generated at the visual level: just as in the first illustration the narrator is sitting in a rowing boat — as a young child with his grandfather — so too at the end of the story he is again sitting in a boat (albeit one with an outboard motor) — as an adult with young Marius, the finder of the message. The bottle may have drifted all alone for years in the cold North Sea, but in the end it serves to bring people together.

Translated by Helena Kirkby

By Eva Jaeschke