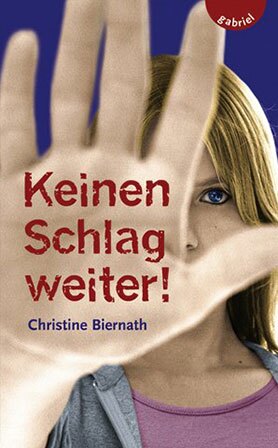

Christine Biernath

Keinen Schlag weiter!

[No more hitting!]

- Gabriel Verlag / Thienemann Verlag

- 2007

- ISBN 978-3-522-30105-3

- 188 Pages

- 11 Suitable for age 12 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Christine Biernath

Keinen Schlag weiter!

[No more hitting!]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Portuguese: Brazil (2007 - 2008).

Sample translations

Review

In her novel about domestic violence Christine Biernath tells the story of a prosperous lawyer’s family. The events of the novel move relentlessly towards their climax, and are recounted from the very different viewpoints of the family’s two adolescent children. In addition, each chapter is headed by a brief comment from a teacher, neighbour or colleague.

Benjamin Schneider is the older of the two children. He is sixteen, and he is sensitive and musical, quiet and reserved. He can remember violent scenes within the family dating right back to his early childhood, but, believing he is incapable of doing anything to stop his father, he suffers in silence alongside his repeatedly beaten and humiliated mother.

Sandra is a bit younger than her brother Benjamin, perhaps thirteen or fourteen. She is completely different from Benny, whom she scornfully dismisses as a ‘wimp’ because he likes classical music and plays piano with his mother. She prefers hip hop and likes going to parties. She is totally unaware of her father’s violent rages, which initially at least are directed solely at her mother. She keeps telling her email friend Laura how cool her father is and how boring and incompetent her mother, who never stops telling her to improve her behaviour.

Biernath has the two youngsters take turns putting forward their point of view, with Benjamin’s memories alternating with Laura’s emails. While Sandra’s emails always relate directly to the events of the day and give an unmediated, unreflective impression of her wants and feelings, and of her rows with her mother, Benny’s account conveys a more complete picture of the family and its social context. His contributions reveal the complexity of his father’s personality: a man who can be tender and loving, but who is also prone to fits of violence directed chiefly at his wife who, instead of leaving him, always sees herself as being to blame. Having found himself a girlfriend, Benny’s self-confidence begins to grow, and this even gives him the courage to intervene against his father and prevent the worst when the crisis in the family finally comes to a head.

By contrasting the perspectives of the son and the daughter the author successfully highlights one of the biggest problems around the issue of domestic violence: the refusal to acknowledge what is glaringly obvious. A taboo is at work here whereby even the family members concerned close their eyes for as long as they possibly can. The experience is humiliating and demoralising, and more often than not the victim suffers from feelings of shame and guilt. Some of Benjamin’s brief memory flashes include self-abasement episodes of this sort on the part of his mother. The boy himself is distressed by the fact that his fear of his father renders him incapable of protecting his mother. His sister, on the other hand, identifies with her sporty, successful father and as a result often adopts his disparaging attitude to her mother. Furthermore, the conflicts that puberty has stoked up within her and which she largely vents on her mother also serve to blind her to the truth.

Thus via a succession of brief episodes the narrative steadily pieces together the complex picture of a family that does its utmost to preserve a façade of bourgeois normality while the hidden reality becomes ever more critical and finally spins out of control.

In her book Christine Biernath contrives to deal with difficult and highly involved issues without presenting them in such a way as to over-simplify them. Domestic violence is by no means uncommon, and often has complex roots. The author manages to convey this complexity very effectively by creating complex characters. They are contradictory individuals who do occasionally become aware of their shortcomings but are nonetheless incapable of altering their patterns of behaviour. By refusing to trot out standard explanations or to glibly attribute blame, Biernath’s book gives us real pause for thought.

Benjamin Schneider is the older of the two children. He is sixteen, and he is sensitive and musical, quiet and reserved. He can remember violent scenes within the family dating right back to his early childhood, but, believing he is incapable of doing anything to stop his father, he suffers in silence alongside his repeatedly beaten and humiliated mother.

Sandra is a bit younger than her brother Benjamin, perhaps thirteen or fourteen. She is completely different from Benny, whom she scornfully dismisses as a ‘wimp’ because he likes classical music and plays piano with his mother. She prefers hip hop and likes going to parties. She is totally unaware of her father’s violent rages, which initially at least are directed solely at her mother. She keeps telling her email friend Laura how cool her father is and how boring and incompetent her mother, who never stops telling her to improve her behaviour.

Biernath has the two youngsters take turns putting forward their point of view, with Benjamin’s memories alternating with Laura’s emails. While Sandra’s emails always relate directly to the events of the day and give an unmediated, unreflective impression of her wants and feelings, and of her rows with her mother, Benny’s account conveys a more complete picture of the family and its social context. His contributions reveal the complexity of his father’s personality: a man who can be tender and loving, but who is also prone to fits of violence directed chiefly at his wife who, instead of leaving him, always sees herself as being to blame. Having found himself a girlfriend, Benny’s self-confidence begins to grow, and this even gives him the courage to intervene against his father and prevent the worst when the crisis in the family finally comes to a head.

By contrasting the perspectives of the son and the daughter the author successfully highlights one of the biggest problems around the issue of domestic violence: the refusal to acknowledge what is glaringly obvious. A taboo is at work here whereby even the family members concerned close their eyes for as long as they possibly can. The experience is humiliating and demoralising, and more often than not the victim suffers from feelings of shame and guilt. Some of Benjamin’s brief memory flashes include self-abasement episodes of this sort on the part of his mother. The boy himself is distressed by the fact that his fear of his father renders him incapable of protecting his mother. His sister, on the other hand, identifies with her sporty, successful father and as a result often adopts his disparaging attitude to her mother. Furthermore, the conflicts that puberty has stoked up within her and which she largely vents on her mother also serve to blind her to the truth.

Thus via a succession of brief episodes the narrative steadily pieces together the complex picture of a family that does its utmost to preserve a façade of bourgeois normality while the hidden reality becomes ever more critical and finally spins out of control.

In her book Christine Biernath contrives to deal with difficult and highly involved issues without presenting them in such a way as to over-simplify them. Domestic violence is by no means uncommon, and often has complex roots. The author manages to convey this complexity very effectively by creating complex characters. They are contradictory individuals who do occasionally become aware of their shortcomings but are nonetheless incapable of altering their patterns of behaviour. By refusing to trot out standard explanations or to glibly attribute blame, Biernath’s book gives us real pause for thought.

Translated by Helena Kirkby

By Heike Friesel