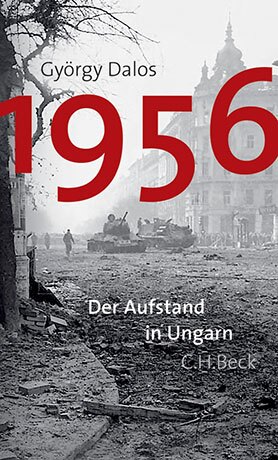

György Dalos

1956. Der Aufstand in Ungarn

[1956. The Hungarian Uprising]

- C.H.Beck Verlag

- Munich 2004

- ISBN 3-406-51863-X

- 248 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

György Dalos

1956. Der Aufstand in Ungarn

[1956. The Hungarian Uprising]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Chinese (2005 - 2006).

Sample translations

Review

György Dalos, born in 1943, was thirteen years old when, within a few hours, a big demonstration in Budapest developed into an armed uprising, whose radicalism was without parallel in the history of the Warsaw Pact. “This event shaped my generation,” writes Dalos. The form of his book is reminiscent of a collage, an approach which is perhaps best suited to the headlong rush of events. For readers who have not previously concerned themselves with the Uprising it serves as an excellent introduction to the importance of these dramatic twelve days from 23rd October to 4th November 1956.

Dalos is not a historian, but a writer. His text is not preceded by any subdivided contents list, and the author also dispenses with footnotes. In part he names his sources in the text itself while in an appendix there’s a selected list of sources in German, Hungarian and Russian which he has used. It’s clear from the beginning that this is a subjective account, whose perspective is characterised by both closeness and distance. According to Dalos he has repeatedly revised his personal assessment and judgement of the events, so important to the Hungarian self-image, and has now, 50 years and several regime changes later, arrived at a position, which allows him to understand the Uprising in all its contradictions and complexity. He has not written a heroic history, but he does succeed in conveying the greatness of individual participants; he hasn’t written a history of atrocities but nevertheless mentions the violent excesses on both sides. And the ambivalent key figures of the Uprising, Imre Nagy and János Kádár are portrayed with all their inner conflicts and equivocation.

Dalos’ account has a basic chronological structure. The extreme concentration of what occurred, however, repeatedly forces him to anticipate the course of events or to look back, in order to link the most important parallel threads of the action. His book moves back and forward between several levels. There are first of all the personal memories of the thirteen year-old, who experiences the revolutionary mood as a fascinating interruption of everyday life in Budapest, without really being able to grasp its significance. Then there are the constantly changing locations of the fighting in the city, barricade building and mass demonstrations, massacres of demonstrators and lynchings by rebels. At the same time, of course, Dalos describes the developments at the government level, the difficult and sometimes chaotic processes of decision-making of the Hungarian and Soviet leaderships. This all takes place in a world political situation, in which Britain, France and Israel had attacked Egypt in order to reverse the nationalisation of the Suez Canal. Nor was any concrete support to be expected from the United States - fear of the risk of a nuclear exchange with the Warsaw Pact was too great.

While the internal logic of events was on the one hand linked to these constellations of world politics, it depended at least as much on the frequently hesitant and indecisive positions of the key political personalities: Imre Nagy, the reformist Communist, who had earlier been expelled from the Party, was installed as Prime Minister by the Soviet leadership right at the beginning of the Uprising. His opponent was János Kádár, who was first at Nagy’s side as new leader of the Hungarian Communist Party but soon defected and took charge of the state in the shadow of the Soviet invasion.

But people who are not usually mentioned in historical accounts are properly acknowledged in Dalos’ book. The author devotes a whole chapter to “the Hungarian freedom fighter”, declared “Man of the Year 1956” by Time Magazine. In this chapter he gives exemplary descriptions of some of the “ordinary” people who fought on the streets of Budapest and other Hungarian cities against Russian control and for civil rights and liberties such as the right to strike and demonstrate and freedom of the press and assembly. Also mentioned here, however, are those with other motives, eccentric self-appointed leaders of the people, criminals or youthful adventurers.

Seen from today the manoeuvring of Khrushchev and the other Soviet leaders may appear transparent, but to look at historical events with the “all-knowing” advantage of hindsight hardly does justice to the contemporaries involved. Dalos succeeds in carefully recounting the multi-layered chaos of these few days and against this background to convey, just how terribly difficult it must have been for Nagy (and perhaps also for Kádár) to find the supposedly right position. Caught between loyalty to the Communist Party and the demands of the Hungarian people both hesitated for a long time before making a decision, and then went in opposite directions.

György Dalos, an author who writes in German and Hungarian, not only conveys historical knowledge, but also gives an impression of the importance of the popular uprising in Hungary’s collective memory. He writes about the specific mixture of nationalism and radical socialist demands and about how the Hungarians felt, to be let down by the West: subjects which could only be freely discussed after the foundation of the Republic of Hungary in 1989. But although, according to Dalos, the demands of 1956 are no longer appropriate to the present day, he is convinced that the spirit of the Uprising continues to have an effect under the surface.

Dalos is not a historian, but a writer. His text is not preceded by any subdivided contents list, and the author also dispenses with footnotes. In part he names his sources in the text itself while in an appendix there’s a selected list of sources in German, Hungarian and Russian which he has used. It’s clear from the beginning that this is a subjective account, whose perspective is characterised by both closeness and distance. According to Dalos he has repeatedly revised his personal assessment and judgement of the events, so important to the Hungarian self-image, and has now, 50 years and several regime changes later, arrived at a position, which allows him to understand the Uprising in all its contradictions and complexity. He has not written a heroic history, but he does succeed in conveying the greatness of individual participants; he hasn’t written a history of atrocities but nevertheless mentions the violent excesses on both sides. And the ambivalent key figures of the Uprising, Imre Nagy and János Kádár are portrayed with all their inner conflicts and equivocation.

Dalos’ account has a basic chronological structure. The extreme concentration of what occurred, however, repeatedly forces him to anticipate the course of events or to look back, in order to link the most important parallel threads of the action. His book moves back and forward between several levels. There are first of all the personal memories of the thirteen year-old, who experiences the revolutionary mood as a fascinating interruption of everyday life in Budapest, without really being able to grasp its significance. Then there are the constantly changing locations of the fighting in the city, barricade building and mass demonstrations, massacres of demonstrators and lynchings by rebels. At the same time, of course, Dalos describes the developments at the government level, the difficult and sometimes chaotic processes of decision-making of the Hungarian and Soviet leaderships. This all takes place in a world political situation, in which Britain, France and Israel had attacked Egypt in order to reverse the nationalisation of the Suez Canal. Nor was any concrete support to be expected from the United States - fear of the risk of a nuclear exchange with the Warsaw Pact was too great.

While the internal logic of events was on the one hand linked to these constellations of world politics, it depended at least as much on the frequently hesitant and indecisive positions of the key political personalities: Imre Nagy, the reformist Communist, who had earlier been expelled from the Party, was installed as Prime Minister by the Soviet leadership right at the beginning of the Uprising. His opponent was János Kádár, who was first at Nagy’s side as new leader of the Hungarian Communist Party but soon defected and took charge of the state in the shadow of the Soviet invasion.

But people who are not usually mentioned in historical accounts are properly acknowledged in Dalos’ book. The author devotes a whole chapter to “the Hungarian freedom fighter”, declared “Man of the Year 1956” by Time Magazine. In this chapter he gives exemplary descriptions of some of the “ordinary” people who fought on the streets of Budapest and other Hungarian cities against Russian control and for civil rights and liberties such as the right to strike and demonstrate and freedom of the press and assembly. Also mentioned here, however, are those with other motives, eccentric self-appointed leaders of the people, criminals or youthful adventurers.

Seen from today the manoeuvring of Khrushchev and the other Soviet leaders may appear transparent, but to look at historical events with the “all-knowing” advantage of hindsight hardly does justice to the contemporaries involved. Dalos succeeds in carefully recounting the multi-layered chaos of these few days and against this background to convey, just how terribly difficult it must have been for Nagy (and perhaps also for Kádár) to find the supposedly right position. Caught between loyalty to the Communist Party and the demands of the Hungarian people both hesitated for a long time before making a decision, and then went in opposite directions.

György Dalos, an author who writes in German and Hungarian, not only conveys historical knowledge, but also gives an impression of the importance of the popular uprising in Hungary’s collective memory. He writes about the specific mixture of nationalism and radical socialist demands and about how the Hungarians felt, to be let down by the West: subjects which could only be freely discussed after the foundation of the Republic of Hungary in 1989. But although, according to Dalos, the demands of 1956 are no longer appropriate to the present day, he is convinced that the spirit of the Uprising continues to have an effect under the surface.

Translated by Martin Chalmers

By Heike Friesel