Children's Books

Nikolaus Nützel

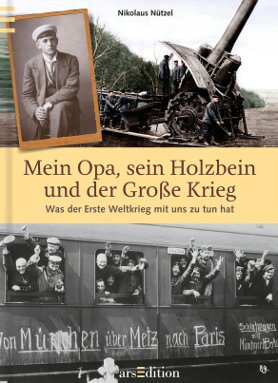

Mein Opa, sein Holzbein und der Große Krieg

[My grandpa, his wooden leg, and the Great War]

Nikolaus Nützel

Mein Opa, sein Holzbein und der Große Krieg

[My grandpa, his wooden leg, and the Great War]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Russian (2012 - 2014).

Review

Why did the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by a high school student in Sarajevo, Bosnia, spark worldwide bloodshed of unprecedented barbarity in the summer of 1914? Who was mainly responsible for the First World War? And how did “the great seminal catastrophe of [the twentieth] century” impact the further course of history?

In Germany’s “super memorial year” 2014 (Translator’s note: 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War, 75th of the start of the Second World War, and 25th of the fall of the Berlin Wall.) alone, monumental new books are filling entire libraries in an attempt to resolve these questions, which remain relevant to this day. Nikolaus Nützel has demonstrated for us the ability to present the essential aspects of the First World War, and its aftermath, on roughly 150 pages—including numerous illustrations, info-boxes, and diagrams—in his young people’s book Mein Opa, sein Holzbein und der Grosse Krieg (My Grandpa, His Wooden Leg, and the Great War). History, politics, and the history of mentalities are conveyed within their far-reaching contexts in a concise and appropriate manner. For example, Nützel explains what people expected from the German Empire’s invasion of Belgium on August 3, 1914, in accordance with the Schlieffen Plan. He depicts the brutality of the battlefield without any sugarcoating, sketches the peculiar dynamics of the war economy, and describes the sinking of the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania. With an eye toward imperialism, Pan-Slavism, and the Pan-German League’s craving for status, he outlines the prologue to the war. Nazi rule and the Second World War move into the focus as the “logical consequence” of the events of 1914–1918—making a reference to a theory that is by no means undisputed among historians. Nützel spans a bridge all the way to present-day wars. But he also talks about neo-Nazis, who march today carrying the flag of the defeated German Empire, and about why no public high schools in the western part of Germany are named after Karl Liebknecht, an antimilitarist and Marxist who was murdered in 1919.

Nützel teaches his young readers by encountering them on equal footing. Using a first person narrative, he approaches the historical events, describing how as a schoolchild in history class he simply could not comprehend the reasons and motives for the outbreak of war. He recalls his uneasiness during a vacation in Verdun, where in 1916 one of the most terrible and protracted battles between Germans and French raged. Most of all, however, it is through his own family history that Nützel succeeds in vividly illustrating world history. The fate of his grandfather, a Protestant pastor named August Müller, serves as the common thread running through the ideas and emotions of previous generations. As a typical representative of the “hurrah patriotism” of the Wilhelmine period, the young August Müller enthusiastically went to war in August 1914, only to return home just a few weeks later. A piece of shrapnel had cost him his left leg. From then on he clung ever more desperately to his nationalist sentiments. He viewed the Treaty of Versailles as a disgrace that had to be avenged at all costs, and was outraged by the democracy of the Weimar Republic. Even before 1933 August Müller had already become a committed supporter of Hitler.

Nützel knows very well how challenging it is for today’s young people to grasp the abstract, unfathomable numbers of casualties of the war. That is why in addition to his grandfather he also lets other individuals stand out from the masses and speak: He mentions the fate of the British soldier Thomas Highgate, who at nineteen years of age was shot as a deserter. And a letter written by the 22-year-old German frontline soldier Franz Blumenfeld is quoted: “One thing weighs upon me … the fear of getting brutalized” Blumenfeld wrote to his family in October 1914, when he was shocked to see that he was becoming accustomed to seeing corpses and hearing the screams of the seriously injured. Two weeks later the young man, who wanted to complete his law studies after the war, was dead.

Through these individualizing images and his consistently subjective view of history, Nützel does not even come close to hazarding any ultimate explanations. All the more dauntlessly he broaches the big questions in his small, smart book, not only historical ones, but also philosophical and moral ones. “What makes up a person?” “Can people exist without war?” “How would I have acted if I had been in the same situation as my grandfather?” For Nützel there aren’t any answers to these questions. But they affect us all and show us clearly and unmistakably “what the First World War has to do with us.”

Translated by Allison Brown

By Marianna Lieder

Marianna Lieder works as a freelance journalist and literary critic for publications including the Tagesspiegel, the Stuttgarter Zeitung and Literaturen. She has been an editor at Philosophie Magazin since 2011.