Fiction

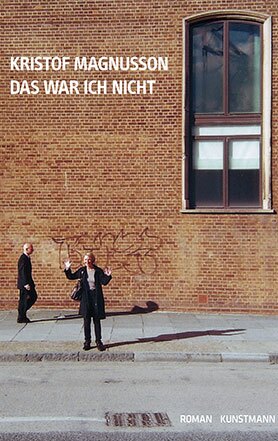

Kristof Magnusson

Das war ich nicht

[It wasn’t me]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Spanish: Argentina (2009 - 2011).

Review

The banking and financial crisis convulsed the world economy and sparked profound global change. But who was actually responsible? In his second novel, It Wasn’t Me, Kristof Magnusson seeks – and finds – answers to this complex question.

Not only does he present readers with an entertaining and cleverly constructed story, he unravels the complex economic issues in a way that reflects thorough research, yet is humorous and easy to understand.

Magnusson’s novel is especially noteworthy for its elaborate composition, a sophisticated, ever-tighter interweaving of different storylines that increases the suspense and vividly illustrates the many-faceted nature of the financial crisis. With three protagonists alternating as narrators, the reader rapidly shifts perspectives, jumping from London to Hamburg and from Chicago to provincial North Frisia. Rather than progressing chronologically, the plot weaves and doubles back upon itself, as Magnusson repeatedly depicts one and the same incident from the varying perspectives of his three protagonists.

To wit: Meike Urbanski, a young literary translator from Hamburg’s hip Schanzenviertel who has “worked well” with her boyfriend for ten years. After steps two, three and four of their relationship, i.e., building up a mutual circle of friends, moving in together and starting to think about children, she’s ready for the fifth and last step: the clandestine flight from her middle-class existence to the middle of nowhere, North Frisia. Here she hopes to assuage her homesickness “for a place I didn’t know” while focusing in peace and quiet on her translation of the new novel by bestselling American writer Henry LaMarck. Every morning she checks her mailbox, hoping to find the manuscript at last so that she can begin with the translation.

What she doesn’t know is that not a word of the novel has been written, not even an outline – Pulitzer prizewinner Henry LaMarck is on the run as well, from his publisher, from the press, and most of all from himself. In an attempt to hold his own with the other brilliant guests on a BBC talk show, he’d spontaneously and rashly announced a novel about September 11, whipping up even more interest by claiming (falsely, of course) that he’d secretly been working on it ever since the terrorist attacks. Now his publisher expects the novel of the century, with a first printing planned in the millions. With pressure mounting on all sides, LaMarck goes into hiding, hoping to find the inspiration for the promised novel after all.

At the same time, Meike Urbanski spontaneously decides to travel to Chicago herself to drum up the urgently-awaited manuscript. On the basis of this constellation alone – overzealous translator in search of her fugitive, creatively-blocked author – Kristof Magnusson unfolds a grotesque web of relationships with considerable comic potential. But rather than leave it at that, he augments the cast of his novel with a third character who increasingly emerges as the secret crux of the action.

The man completing the trio is 31-year-old Jasper Lüdemann, who has made it from a village near Bochum all the way to Chicago, where he’s pursuing a career as a trader at the investment bank Rutherford & Gold. Though the aspiring banker can’t afford to indulge feelings of pity and sympathy, he tries to help out a colleague whose bad speculations have gotten him into a fix. However, Jasper’s rescue attempt spins out of control; his speculative transactions run up a steadily mounting deficit. As his fear of discovery escalates, he runs into the young translator Meike, who immediately makes him feel that “everything will work out somehow”. Now he is determined to see her again.

For her, however, “this guy was as boring as a guy with a suit and Blackberry could be”. She is interested only in Henry LaMarck, but he wants to have nothing to do with her. When she finally tracks him down, he unceremoniously ejects her from his hotel room. He has other things on his mind: reading the Chicago Tribune, he happened across a photo of the dapper young stockbroker Jasper Lüdemann and immediately fell in love with him. Jasper’s face seems to hold all that he has been searching for the past year: “A distraught banker – what a perfect symbol of the world that was attacked on September 11.”

Jasper, in turn, only tolerates Henry LaMarck in the hopes of impressing Meike with his new acquaintance. As an excuse for regular contact, LaMarck authorizes Jasper to speculate with his considerable fortune. But Jasper doesn’t even get the chance. However insignificant he finds the damage he has caused the company (“You shouldn’t call it peanuts, but basically it was”), the loss of – by now – six billion dollars plunges Rutherford & Gold into bankruptcy, rocks the stock market and forces the banker to flee to Germany. Before heading for the airport, he spontaneously decides to transfer LaMarck’s entire fortune to Meike’s account and takes leave of his workplace with one last, brief note: “Sorry. Jasper.”

And so, to the surprise of all, both Henry LaMarck – convinced that he must stay in hiding because Jasper’s transactions have ruined him – and Jasper Lüdemann himself converge upon Meike’s house in provincial North Frisia.

Kristof Magnusson tops off this tragicomic triangle with an extravagant yet perfectly orchestrated happy end: Jasper and Meike are united, the translator’s career takes off, and Henry LaMarck finds the tranquility to settle into a well-deserved retirement, even gaining back the fortune he thought was lost.

With great narrative finesse, Kristof Magnusson catapults his characters into the midst of the global financial crisis. Fascinatingly, the author began writing before the global crisis – almost as if he saw it coming. The shifting perspectives and the playful approach to his characters, who gain more and more depth as the plot progresses, transform the complex financial subject matter with impressive ease into an accomplished work of literature. Magnusson even manages to give a face to the elusive financial crisis: Jasper Lüdemann’s. And, surprisingly enough, the face is quite a sympathetic one.

Translated by Isabel Fargo Cole