Non-fiction

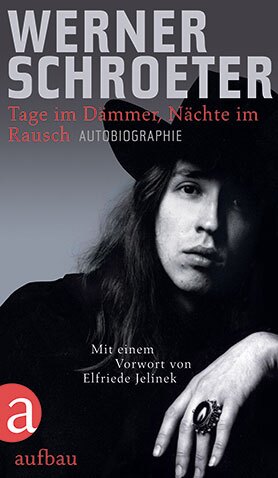

Werner Schroeter

Tage im Dämmer, Nächte im Rausch

[Twilight days, drunken nights]

Review

It’s said that when you die your whole life is supposed to flash before your eyes. This is a lonely experience for many people. But happily not for the director Werner Schroeter. In the summer and autumn of 2009, the journalist Claudia Lenssen accompanied the fatally ill artist to cafes and restaurants and recorded his memories. He died of cancer a few months later, aged sixty-five. Fifty hours of material were gathered at the meetings, which Lenssen has used to create an impressive life-history, which she confidently calls ‘autobiography’. Blessed with the memory of an elephant, Schroeter takes stock of his unconventional life in these pages.

During his lifetime Schroeter was considered to be the great outsider of New German Cinema, largely overshadowed by his friends Fassbinder, Herzog and Wenders. His numerous prizes – including the Golden Bear for his drama ‘Palermo or Wolfsburg’ – did little to change that. But Schroeter is anything but competitive. Schroeter is an artist, through and through. As far as he is concerned there is no border between art and life. Uncompromising, radical and provocative, he follows his intuition, directing more than thirty films and staging almost ninety plays over four decades. He is a chain-smoking creative machine who really comes into his own at night. He distances himself from the bourgeoisie through his outward appearance: rings, necklaces, brooches and scarves are as much a part of his extravagant style as his signature wide-brimmed hats. He mostly wears black, with leather trousers, long hair and a goatee. He is openly homosexual.

Schroeter uses numerous anecdotes to describe growing up in the fifties in Bielefeld and in northern Baden-Württemberg, where his classmates only stop beating him up when he gives it to the intellectuals. He lovingly remembers his Polish grandmother Elsa, whose imagination has a lasting influence on him. As well as a radio programme from 1958 which changes his life: hearing Maria Callas singing an aria was a revelation for the quiet, gentle Werner. After his A-levels he wants to ‘learn to love’ and then to take his own life. Eros and Thanatos become extremely important. He refers repeatedly in his memoirs of his ‘tragic world view’.

He soon turns his back on the new film academy in Munich. It is the artistic process which interests him. Encouraged by his lover Rosa von Praunheim, he shoots his first 8mm film in 1967. His inspirations were Carl Theodor Dreyers’ historical film ‘The Passion of Joan of Arc’ from 1928 and ‘The Songs of Maldoror’ (1874), the sixty-verse-long work by the poet Comte de Lautréamont. Schroeter’s memories are frequently concerned with the storylines of his films, operas and plays, as well as with the often strange stories about how they came into being, with actors and love affairs – and above all with his longstanding muse and companion, Magdalena Montezuma.

Schroeter largely lives out of a suitcase. His projects and passions lead him to Lebanon, Mexico, India, Brazil, Italy and the Philippines. He lectures at universities in Argentina and California. But the country of his dreams is Portugal. He would have liked to spend his latter years here. Schroeter was a true gentleman, fluent in six languages. Although he tells how he values German music and literature, he has no time for the German mentality. He describes the ‘calcification of emotions’ in his native country, which ‘is regarded as progress towards greater productivity.’ Here speaks a true romantic.

Theatre and opera stand as alternatives to contemporary reality for Schroeter. In them he celebrates beauty, seeing them as vehicles for humanist ideas. His autobiography presents the vivid picture of a bohemian who allows himself to drift long, carefree and easygoing, living in the here and now without thinking about material things. From time to time Schroeter drinks a bottle of cognac during the day, as well as trying heroin. The committed Christian confesses with remarkable honesty that he has never protected himself during sex and was also once in bed with a priest. The reader becomes witness to an excessive life without a security net.

Alongside its ruthless honesty, the book’s great strength lies in Schroeter’s ability to recall episodes in minute detail, even when they occurred decades ago. The impressive stories astound and amuse: his dispute with Franz Josef Strauß, the animated conversations with Michel Foucault. How, as a homosexual, he got a female friend pregnant. Being sick on Maria Schell’s mink coat after food-poisoning from eating oysters. Or how he made fun of Josephine Baker’s pubic wig at a concert in Beverly Hills and became the subject of her furious stares.

It is an autobiography which succeeds in depicting the life of an extraordinary person, as well as moving and entertaining its readers. Doubtlessly the work of a great artist.

Translated by Sheridan Marshal

By Daniel Grinsted

Daniel Grinsted is a cultural critic with a degree in Anglo-American literature. He works as a freelance arts journalist for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Zeit Online, Literaturen, Börsenblatt and other media.