Fiction

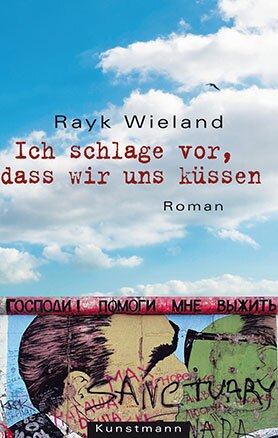

Rayk Wieland

Ich schlage vor, dass wir uns küssen

[I’m proposing that we kiss]

Review

It’s twenty years ago now that Germany saw the unthinkable: the collapse of the Wall that had divided Berlin and Germany into East and West. Soon there were calls for an adequate artistic response, a novel that would render this unique event in suitable literary form. The result was nothing less than the development of an entirely new genre: theWenderoman (novels about the fall of the Wall).

Many authors from the former GDR as well as West Germany have tried their hands at it. Following Günther Grass’ Too Far a Field (1995), Thomas Brussig’s Heroes Like Us (1995), Ingo Schulze’s New Lives (2005) and, last but not least, Uwe Tellkamp’sDer Turm (The Tower, 2008), the demand for a literary confrontation with the past now seems fulfilled and public interest in the topic more or less satisfied.

But for all the wealth of Wenderomane, a new book has appeared that shouldn’t be missed. This, you see, is noWenderoman à la Grass or Tellkamp; it’s a parody of the genre. I’m Proposing That We Kiss is the charming title of Rayk Wieland’s no less charming and extremely witty novel.

One day the protagonist, Herr W., finds in his mailbox an invitation to read his poems at a symposium entitled “Poets, Dramas, Dictatorship: Risks and Side Effects of Underground Literature in the GDR”. At first Herr W. doesn’t know what to make of the request; after all, or so he claims, he wasn’t even a poet. But slowly he begins to remember: “My memory started up slowly, but at least it reacted. Eternities passed in inner review. Decades went by. Nations vanished. Walls fell.”

He recalls Liane from Munich, the flame of his youth, with whom he wrote love letters for several years while the Wall still stood. And yes, now he remembers, some of the letters did include a poem or two in the hopes of impressing her. He applies to see his Stasi files, which had never interested him before in all these years. “Why was that, you ask? I always thought it was, how should I put it, just too inane.” He learns that the Stasi had intercepted all these letters and poems and analyzed them for subversive ideas. And that as a mere teenager he was identified as a potential enemy of the state and put under surveillance.

Years of surveillance, even by friends and acquaintances, repeated invasions of his private sphere – the files tell Herr W. things that would leave others outraged or horrorified. Not W.. He’s blasé about it, at most amused: “An intelligence service that took an interest in the pubescent protuberances of a 16-year old had to be unhinged in its innermost central cerebral core, completely off its rocker. Quite possibly this state [...] ultimately addled its wits entirely by obsessively concentrating its special forces on harmless hobby existentialists like myself.” As an example he cites the “Group 61” which he founded and which the Stasi also had in its crosshairs – its members included, aside from W., a guinea pig and a grandfather clock.

People who learn that they were under surveillance do not typically react by making fun of it – in this sense Wieland’s book strikes a highly unusual note in the spectrum of confrontations with the GDR past. All the things that are usually condemned about the GDR, all its shocking or sobering aspects are held up to ridicule by the narrator, relativized or downplayed. As far as the accusations against the Stasi are concerned, he notes that in the GDR everyone monitored everyone else – workers’ collectives, work brigades, acquaintances, house wardens. “Really it hardly mattered that the Stasi nosed around as well, or at least it hardly bothered anyone.” And elsewhere he writes: “Access to files. Stasi. Gauck Commission. Recruitment of Unofficial Collaborators. Individual surveillance operation. Words lacking all charm whatsoever, prompting, in me at least, an enormous upwelling of boredom.”

However, Wieland takes an ironic distance not just from the general outrage over the misdeeds of the East German state, but also from the parallel cult of memory that developed in the years following the fall of the Wall. In a “Time Travel Agency” he books a “regression guide” into the GDR, but all he manages to relive is the memory of his uninhibited binges with cheap Eastern European rotgut – and the headache to go along with it.

Given Herr W.’s ex post facto mockery of the GDR and everything associated with it, it’s not surprising that back when he was a citizen of the “Workers’ and Peasants’ State” he already regarded it with sarcastic detachment. However – and this is another one of the novel’s ironic touches – we learn this only from the reports in his Stasi file, as he himself keeps suffering from memory gaps. W. clearly belonged to the GDR’s Bohemia, leading a life far from the party line. “Behind it, next to it and beyond it there were plenty of beautifully-functioning parallel, alternate and under-worlds.”

After his apprenticeship, instead of taking his studies seriously, he spends his time hanging around, drinking beer, meeting the strangest people and having peculiar adventures. Lottery winners, driven to despair by the impossibility of spending their money in the GDR; the glorious career of an entrepreneur who runs the lavatories on Alexanderplatz and Friedrichstraße; his friend Moses, who applies for permission to leave the country because the GDR lacks golf courses; and the positive sides to the Stasi – at least they read his poems. Clearly, W. led quite a pleasant existence in this “El Dorado of the niche forms”. Even the system’s impending collapse hardly seems to have captured his interest. In 1989 he and his friends watch with beers in their hands as the masses demonstrate and think up nonsense slogans for their banners: “First Spray, Then Walk Away!” Even the news that the Wall has fallen leaves him unmoved; as everyone else flocks toward the just-opened checkpoint at Bernauerstraße, he lingers over his cigar and Cuba Libre in a bar (to the great displeasure of the waitresses) and philosophizes about the mischief caused by open doors.

Of course one wonders to what extent Rayk Wieland’s experiences parallel those of his Herr W.. The autobiographical reading is tempting, but should of course be avoided. According to the author, he and W. have the Stasi file and the West German girlfriend in common, no more. But autobiographical or not, there is no doubt that these sorts of parallel lifestyles existed in the GDR. And the remarkable thing about this entertaining book is the hilarious and madcap way in which it subverts the standard discourse about the GDR.