Fiction

Ingo Schulze

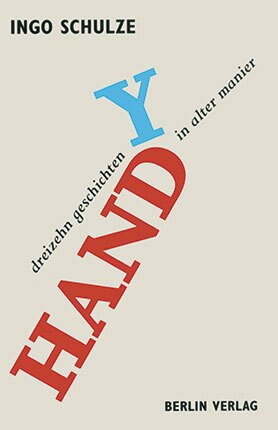

Handy. dreizehn geschichten in alter manier

[Cell phone. thirteen stories in the time-honored mode]

Ingo Schulze

Handy. dreizehn geschichten in alter manier

[Cell phone. thirteen stories in the time-honored mode]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Portuguese: Brazil (2007 - 2008).

Review

Once again in his new volume of short fiction, Cell Phone, Thirteen Stories in the Time-honored Mode, Ingo Schulze demonstrates that he is one German literature’s most important contemporary authors—and a master of opening lines: “I still don’t know even now what to make of it. Was it a catastrophe? Was it a bagatelle? Or simply an everyday event? For me the worst thing was the minutes that followed [ . . . ].” Just as here, Schulze’s quasi-intimate tone pulls the reader into story after story from the very first sentence. Almost off-handedly he creates an illusion of both immediacy and covert tension, not only in terms of the unfolding story, but also as regards the question of what role chance or even fate plays in these narrated slices of life (and perhaps of all our lives).

All these stories have a tinge of something unfathomable about them, maybe even of fate itself, which in turn becomes a theme of its own. As indicated in the introductory motto by Friederike Mayröcker, the book is about the “fundamental questions of life,” a task which literature sets itself—circling, searching, probing—even when it can never provide unequivocal answers. Ingo Schulze’s thirteen stories in the time-honored mode are about wonderfully palpable characters between thirty and forty years old—that is, his own generation. Often they are or were lovers, and often at issue is that crucial, usually unnoticed, moment in which love begins to change and, if worse comes to worst, to evaporate.

With a gift for perceptive observation and at times childlike wonder, Schulze lets his characters tell us about such barely noticeable slices of life, about the disarray in their souls and relationships; and despite the many recurring moments of recognition, each story is fresh and unique. To our great astonishment and pleasure, we follow Schulze as he circumspectly reveals the painfully delicate spot in each of his characters or constellation of characters and exposes the complicated structure of their internal and external reality.

As a result, along with an awareness of the inexplicable, a kind of melancholy, a sense of something lost and unrecoverable, pervades these—sometimes more, sometimes less—everyday moments of narrated life. At the same time the stories display a subtle humor, which arises at times from the amused distance that comes with hindsight, and always from Schulze’s alert eye for the frequently unintentionally comical turns human relationships can take. And so the tone of these encounters, usually narrated in the first-person, is always light, indeed cheerful.

This characteristic Schulze sound is also what links these stories and, despite their very disparate settings—the thread of narrative is spun from Berlin, to Estonia, to New York—fashions them as parts of a shared cosmos: a world that has undergone monumental changes, both private and historical, and that almost always exerts its influence at some crucial, yet imperceptible moment only partially shaped by the characters themselves. “In any case, the fact is that not only my own life has changed. The lives of us all have taken a different course over the last few years. And that may perhaps—perhaps—be the reason I finally found myself in a position to venture a story about Estonia.” These words are taken from the story “Estonia, Out in the Country,” which is not just about a bear riding a woman’s bicycle, but above all about a new sense of life and the strategies of survival appropriate to it in post-socialist era.

Schulze’s stories all deal with the recent past and immediate present, but with a perplexing simplicity that always proves to be an ingenious construct, a heightened form of the quotidian. “Exhausted by this overload of impressions and incapable of finding some appropriate way to order and process what I had experienced, I closed my eyes,” the narrator says at the end of “Writer and Transcendence”—after having just processed it all by telling his story. The perfection of Schulze’s ordering of experience lies in the way any sense of aesthetic construction instantly vanishes, leaving us readers with the feeling of being eye-witnesses to the events so coolly spread out before us.

With just a few strokes Schulze manages to create characters and situations so vividly three-dimensional that the distance between the narrated world and the real world seems totally surmounted, even though their presumptive authenticity is always part and parcel of a marvelously well thought-out interplay between reality and fiction, one component of which is that the first-person narrator is assigned the characteristics of his own authorship. One narrator has (like Schulze) written a book called 33 Moments of Happiness, another an epistolary novel entitled New Lives (which the real author published two years ago), and yet others have traveled to near and distant cities to read their works, to the same places where Schulze himself has been a guest for an extended period. None of these narrators is fully congruent with the real author, they are all only fragmentarily his embodiments—and fictional characters at the same time. This is not merely some self-referential game, but part of a conscious meshing of the lines separating literature and reality.

In each of these stories there is something like an unprecedented event that unsettles personal convictions and disrupts social frameworks. Schulze’s utterly contemporary stories have the density of the well-made novel; in their elegance and casual ease they take aim at a turning point that typically remains enigmatic. It is impossible to give each of these fascinating stories its due here. All I can do is recommend you read them—and enjoy their time-honored and yet wonderfully timely “mode.”