Stephan Lehnstaedt

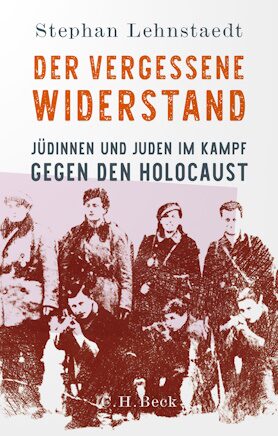

Der vergessene Widerstand. Jüdinnen und Juden im Kampf gegen den Holocaust

[The Forgotten Resistance. Jews in the Fight Against the Holocaust]

- C.H.Beck Verlag

- Munich 2025

- ISBN 978-3-406-83030-3

- 383 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

For this title we provide support for translation into the Polish language (2025 - 2027).

Sample translations

They were nevertheless not lambs

“Let us not go like lambs to the slaughter!” With this, the partisan Abba Kovner called upon his supporters in 1941 to engage in armed resistance against the imminent extermination. In any case that is how he later remembered in a manifesto that marked a historical turning point—away from the long tradition of Jewish forbearance, and toward a self-confident Judaism capable of defending itself. This struck a chord in the young State of Israel in particular, which is part of the story of its impact. Kovner’s heroism cast a long shadow, however, that covered up a lot of other things.

The same was true of the Warsaw ghetto uprising. As an outstanding act of Jewish resistance that lasted three weeks, its story is not only the most documented, but also the most frequently told: in books of remembrance and numerous film adaptations. Precisely the focus of commemoration on the open revolts, as also resonated in Willy Brandt falling to his knees in 1970 at the memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, has also had tragic consequences for the commemoration of other, “smaller” acts of resistance. Whatever did not fit into the heroic narrative fell into oblivion, interestingly enough by both Jews and non-Jews.

.

The historian Stephan Lehnstaedt finally supplements this image with all the more quiet heroes who were swallowed up by the course of history: leaflet makers, escape helpers, bomb makers, archivists, saboteurs, often active in small or very small groups, and sometimes on their own, since most of them did not know about each other. And in the underground, it was often difficult to distinguish friend from foe. In contrast to the myth of passivity, some of them continually thwarted or at least hindered the plans of their persecutors. Lehnstaedt’s book also acknowledges, for the first time, the role played by women in the Jewish resistance. In view of the impending extermination they were able to slip into roles that would not have been open to them under other circumstances.

People such as Oswald Rufeisen come into view. A Polish Jew, while fleeing he applied to be a translator at German police stations in what is today Belarus. When the ghetto there was to be liquidated in 1942, he warned the residents and saved hundreds of lives. Or the Argentina-born Adolfo Kaminsky: After going into exile in Paris, he ran a forgery workshop where he prepared passports, baptism certificates, food ration coupons, and other documents that were then passed on by female couriers. Certainly it would be too much to speak of a comprehensive, organized resistance, and many of these actions have only been documented through lucky coincidences. In a situation where news travelled very slowly and every note could be a treacherous denunciation, secrecy was the top priority. That too, complicated efforts to document the actions after the fact.

It remains a puzzle with necessary gaps that Lehnstaedt put together out of letters, diaries, personal memories, and archives created in secret. The fact that he was so impressively successful despite the uncertain sources was not least due to his broadly defined concept of resistance as “people asserting themselves and humanity in the face of total violence.” Lehnstaedt thereby confronts a historical determinism that presents the Holocaust as an inevitable fate and, at the same time, he gives the dignity of active subjects back to those who protested against it as best they could. Even though many – most – of them died in the end, they were nevertheless not lambs. The only question that was not sufficiently answered was how forgetting could be so widespread among Jews and non-Jews alike.

The final chapter is dedicated once again to the direct and detoured paths of remembrance policy that commemoration took in the postwar years. Whereas in the newly democratic Federal Republic (West Germany) the conservative resistance around Stauffenberg overshadowed everything else, commemoration in the East Bloc countries was nationalized: There only a Communist-Party Jew was considered a good Jew, who also had to comply with the doctrines of the Cold War. In Israel, in turn, a military understanding of readiness to defend prevailed that to today determines all interactions with the neighboring countries. However you choose to assess that, Abba Kovner still has an impact today.

Translated by Allison Brown

By Thomas Groß

Thomas Groß is a freelance journalist in Berlin and works for various media including the Deutschlandfunk Kultur public radio station and Tagesspiegel daily newspaper.

Publisher's Summary

The Nazis could conceive Jewish people only as passive victims. But many Jews fiercely resisted this image. However not many people are aware of the fact that 3000 Jews were active in the resistance in Germany alone. Stephan Lehnstaedt gives us a long overdue insight into this littleknown aspect of history. He reminds us of an unprecedented fight against dehumanisation – a fight for dignity, culture and the right to live.

‘Hitler wants to kill all the Jews in Europe.... Let us not go like lambs to the slaughter!’ declared the student Abba Kovner in 1941. His resolute stance was shared by thousands of Jews in occupied Europe. They all rebelled against Nazi oppression, harassment and plans for their annihilation – even though their brave actions went unnoticed by the public and researchers for a long time. Now, for the first time, Stephan Lehnstaedt gives us an overview of the different forms of Jewish resistance in the Nazi state and its territories. He tells the story of people who stood up for themselves and others even in the face of death by archiving knowledge or helping people to flee, or through acts of sabotage, uprisings, or armed resistance. This is a long-overdue reminder of a forgotten war which was not only, but primarily, about sheer survival.

(Text: C.H.Beck Verlag)