Fiction

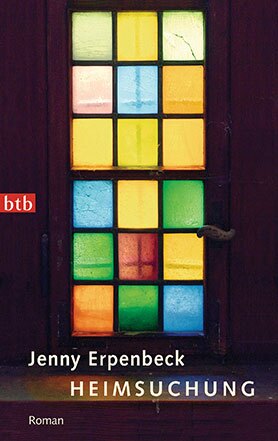

Jenny Erpenbeck

Heimsuchung

[Visitation]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Portuguese: Brazil (2007 - 2008).

Review

Recently, a prize was awarded in Germany for the strangest book title. Perhaps someday there will also be an award for the most telling book title. If so, then Visitation, the new novel by Jenny Erpenbeck, will stand an excellent chance of winning. Yet even without such a prize, the author deserves kudos for her choice of title. Visitation – in its appealing ambiguity, this one word captures the entire doom and tragedy that make up this slim 200-page novel. Visitation revolves around the subject of (re-)visiting in the broadest sense of the word. The novel asks what it means to visit one’s past – should one, in fact, happen to have a past of one’s own. Yet Visitation also stands for a calamitous event, for harassment and vengeance, for the horror of aggression and of being attacked.

The novel’s setting is a tract of land on the banks of Scharmützelsee Lake in Brandenburg. At the beginning of the 20th century, a small-town mayor parcels the property and sells it to city-dwellers seeking a relaxing getaway. Soon, a summer house is built, together with several adjoining buildings. The location is idyllic. During the following decades a colorful array of people spend their summers there, picking raspberries in the gardens, swimming and sailing on the lake, and enjoying the natural surroundings. The area seems to satisfy many people’s desire for a sense of place. It is, as the occupants once painted on one of the doors, a little Garden of Eden. Yet as we all know, nothing lasts forever. Suddenly, “a hole in eternity” appears, and sooner or later the various owners, visitors and renters are all forced to leave.

Aside from the prologue, which illuminates the glacial origins of the region around Scharmützelsee Lake, this round dance of possession and loss begins with the above-mentioned mayor and his family at the outset of the 20th century. Then, in the 1930s, an architect purchases a section of the property and builds a house on it. As his Jewish neighbor is forced by the Nazis to relinquish all of his belongings, he is able to buy the adjacent property at a good price. However, not even the architect can enjoy his new home forever. After weathering both the war and the Russian occupation, the East German regime forces him to flee to the West. A couple, both writers, thereupon return from their Communist exile and settle in the house with friends and relatives for a long stay. Over the span of several decades, the property is thus the site of uninterrupted coming and going. Then 1989 finally puts an end to everything: the house and property fall victim to the well-known disputes concerning inheritance and repatriation.

The individual destinies and stories – a total of twelve – are told with great reserve and are almost fragmentary in nature. The author even largely forgoes names; instead, she refers to the characters by their function, such as “The Red Soldier”, “The Subtenant” and “The Unauthorized Owner.” Although each of the lives of sketched here would provide enough material for stories of their own, Erpenbeck consciously omits information wherever possible. She is not interested in the individual fates of her characters, but rather in what makes certain episodes of their lives so exemplary and representative of historical circumstances.

As a sort of refrain, a chapter devoted to the gardener is interposed between the other individual episodes. There is something magical and mythical about his presence in the novel. No one knows where he comes from (“maybe he has always been here”), and no one knows where he finally goes. Unaffected by the dramatic vicissitudes of history, he is always seen attending to his same garden tasks. No matter who happens to be either living in the house or leaving it, the gardener plants, trims, pulls weeds and “waters roses, bushes and saplings twice a day during summer, once at daybreak and once at dusk.” As though to underscore the steadfast nature of his livelihood, lists such as this one are repeated word-for-word.

Repetition and rhythm – they are the two salient features of this meticulously constructed narrative. The text is linguistically and stylistically so rigorously arranged and the individual narratives so skillfully interwoven – through allusions, references, wordplay and motifs – that at times the novel is more evocative of lyrical speech than of traditional prose.

Erpenbeck’s language repeatedly demonstrates its extreme versatility, though always remains finely tuned to its respective content. Thus, at the outset of the novel, the narrative voice is immersed in antiquated terminology and customs of the 19th century, yet quickly restricts itself to unemotional descriptions during the sections about the gardener. With its numerous temporal transitions, the chapter about the Jewish family is so subtly fashioned that readers will find themselves unexpectedly confronted with the catastrophe that has, of course, long since been set in motion. Here, too, sentences and entire passages are repeated as in a refrain – which, in this context, is clearly reminiscent of Celan’s Death Fugue.

The fact that Jenny Erpenbeck grew up in the former East Germany would no longer be of any great significance to her generation of German writers (Erpenbeck was born in 1967) were the story she is telling not partially her own. The house in the novel once belonged to her grandmother, with whom she regularly spent her vacations. Readers will discover the author in the character of the granddaughter – the one who ultimately has to authorize the house’s demolition. That Erpenbeck transcends her personal memories and, instead, uses her own past as a means to trace the fateful history of 20th century Germany is an additional quality of her novel. This universality grounded in personal experience makes this book much more than a mere family saga.

Translated by Franklin Bolsillo Mares