Children's Books

“History through stories”

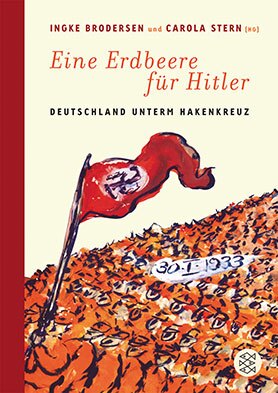

“Hitler” was the name a horticulturist and ardent Nazi supporter from North Germany wanted to give a brand-new and highly successful variety of strawberry in the summer of 1933. This tiny footnote in botanical history exemplifies the absurdity and outlandishness of Hitler-worship after the NSDAP’s success in becoming first the ruling party and then the sole political party in Germany, and graphically demonstrates the universal gullibility of the period that often appears to adults and young people today so baffling and even ludicrous. In their book, Carola Stern and Ingke Brodersen have succeeded in giving us a clearer picture of the rise of Nazism, and more especially of daily life and of the social mechanisms at work in Germany “under the swastika”. In six of the book’s chapters, six different authors deal with various aspects of life between 1933 and 1945. Some of these chapters are autobiographical, others fictional — but they are prefaced by an introductory section entitled “The ‘Führer State’. On the Rise of a Dictatorship” that is a purely factual overview, and as such forms a solid background to the chapters that follow it.

The narrative sections of the book are interspersed with information boxes that serve to explain concepts and institutions specific to the period, and thus constitute a kind of glossary spread across the book as a whole.

Three of the six narrative sections tell the story of everyday life in the 30s and 40s — though from very different perspectives. The chapter “Mit dem Führer auf Fahrt” (“Hiking with Hitler”), which focuses on Nazi youth organisations, depicts three children with very different experiences of Nazi-controlled childhood and adolescence. For the son of a family marked by unemployment and abject failure, the Hitler Youth represents his first ever chance to outdo others, experience adventure, and taste power; the daughter of a somewhat sceptical couple, on the other hand, uses absorption into the organisation as a way of distancing herself from her parents and their views; whereas the Christian girl from a protestant family finds herself doing a dangerous double act in her attempts to honour both the values prevailing at home, and the values prevalent at school and in her youth organisation.

In the chapter entitled “Warum muss ein Soldat töten?” (“Why Do Soldiers Have to Kill?”), Ursula Wölfel, a well-known German children’s author born in 1922, recounts the story of a block of flats in the Ruhr area. As time goes by the inhabitants of the house undergo a process of change: boys become soldiers in the Wehrmacht and write letters from the front; political differences turn friends into enemies, while strangers become friends. The longer the war goes on, the harder people become and the more entrenched their positions, while their subsequent lives are affected for ever by their experiences in the communal air raid shelter.

The everyday life of the majority of the German population is not the only thing depicted in this book, however, for it also focuses on the fate of Germany’s Jews. In the chapter “Himmel und Hölle” (“Heaven and Hell”) Miriam Pressler recounts the doleful story of Hannelore, a Jewish girl from Leipzig, whom we first see in a zionist youth group preparing to emigrate to Palestine. When the Second World War begins in 1939 these young people are taken to Denmark, where they live in relative safety with Danish families — until they are hauled off to Theresienstadt concentration camp by the Nazis. Their lives are saved purely and simply by the fact that they were taken there from Denmark, for they are rescued from the camp by the Danish Red Cross shortly before the end of the war, and thus saved from deportation.

The chapter “Sag nicht, es ist fürs Vaterland” (“Don’t Say It’s for the Fatherland”) shows that it is possible even under the most brutal of regimes to offer resistance. Hermann Vinke’s wide-ranging survey not only covers well-known resistance groups such as the “Weisse Rose” (“White Rose”), but also less well known organisations such as the “Rote Kapelle” (“Red Orchestra”). Vinke’s main concern is to show that despite the enormous risks there were many people whose moral convictions were more powerful than their fear of the regime. Solitary activists like Georg Elser and symbolic figures such as the protestant pastor Heinrich Niemöller rub shoulders here with the seemingly “unpolitical” Swing Kids of Hamburg and the largely aristocratic Wehrmacht officers who planned and carried out the failed assassination attempt of 20 July 1944. This chapter in particular, however, prompts readers to undertake further research, since, given its necessary brevity, it can offer only a preliminary sketch of these multi-faceted movements and individuals.

In the closing chapter the educationist Hartmut von Hentig recounts his experience of the end of the war and of the ensuing developments in Germany in 1945. He writes about such matters as the rumours of Hitler’s death, the deployment of young boys and old men in the Volkssturm militia, the Nuremburg Trials, and the Allies’ negotiations concerning the future of Germany — a country teetering on the very edge of the void.

The two editors see their book as a warning, and as a means of helping young readers in particular to identify totalitarian developments at an early stage, and to oppose them. The book’s depiction of the everyday life of young people make it easier for readers to imagine themselves in their shoes, while the various examples of people who chose to defy the regime demonstrate that for every individual there comes a crucial moment of decision, even though making such decisions often meant putting their own lives at risk. Carola Stern in particular stresses in her afterword how difficult it is for an individual to make a choice that runs counter to prevailing opinion. And she sees her own experience as a frightening example of youthful gullibility and belated insight.