Non-fiction

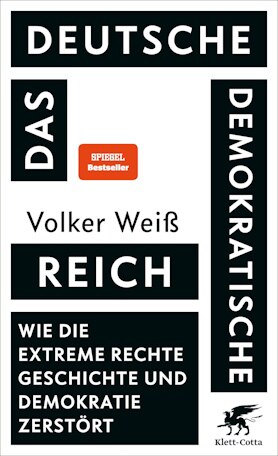

Volker Weiß

Das Deutsche Demokratische Reich. Wie die extreme Rechte Geschichte und Demokratie zerstört

[The German Democratic Reich. How the extreme right destroys history and democracy]

Translation Grant Programme

For this title we provide support for translation into the Polish language (2025 - 2027).

Mechanisms of reinterpretation: The conceptual assault of the new right

The “German Democratic Empire” as a sequel to the GDR, a fantastic fusion of the German Empire (1871 to 1918) and the German Democratic Republic (1949 to 1990) – who even comes up with something like that? In fact it was Jürgen Elsässer, the radical right-wing publicist and activist who announced this vision of another Germany in 2023 at the so-called “Day of German Freedom” in Gera. The question, according to Elsässer, was “whether the eastern part of Germany shouldn’t found a new GDR, albeit not as a socialist but as a German Democratic Empire.” This audacious configuration would involve the exclusion or annexation of the Federal Republic, i.e., the former West German state. The advantage, of course, for easterners would be their continued right to existence. This is irrelevant, however, for right-wing extremists like Elsässer or his close ally Björn Höcke. It is more about the right to dream big, namely of a grand alliance of anti-liberals. Their avant-garde is the eastern German, as imagined by the AfD, the Alternative for Germany party.

“My hope,” says Elsässer, “is distinctly centered on the East, where people are still German and try to defend Germany.” The message is clear: eastern Germans are resisting the influx of migrants. They want to remain German, which Elsässer sees as an act of defense. In this they agree with Putin and Orbán, and everyone else who equates freedom with the protection of national identity. The eastern Germans, as envisioned by Elsässer, are defending Germany’s freedom, not against Putin but against mainstream public broadcasters like ARD and ZDF – that is to say, against the “fake news” propagated in their view by the “lying media” financed by German households by way of mandatory license fees. A new GDR would put an end to all of that.

Historian Volker Weiss endeavors in his new book to identify the occasionally coherent ideological position in the mass of nebulous thought that characterizes the new right. What exactly do people like Elsässer and Höcke want, and do they themselves even know? Their muddleheaded ideas, at any rate, have proven popular beyond their own circle of followers. We are dealing here with self-proclaimed revisionist lay historians, offering us an updated past in which Germany’s history and identity appear in a new, more dazzling guise. Their politics of memory is a far-right version of cultural policy. By asserting their politicized version of history and propagating new narratives of national greatness they hope to lay claim to a new future. Why shouldn’t Germany do what Putin’s Russia has done and might soon be the case in Trump’s America as well: the massive purging of self-critical content from historical narratives? A key question on the extreme right in Germany is its relationship to Russia. Weiss gives a detailed account of the ideas underlying new Russian nationalism, which are resonating now in Germany as well. But what do the AfD and its sympathizers think about Ukraine? And what about Germany’s stance on the Ukraine war? Weiss shows that views in the far-right camp are extremely varied. How would Germany’s Ukraine policy look if the AfD had a say in it? It’s not a pretty sight.

The far right is fond of using big words and empty slogans, which the mainstream media, its avowed enemy, never fails to regurgitate. For example, when Alice Weidel and other AfD leaders refashion Nazism into a “leftist” movement – a myth that Weiss thoroughly debunks. Provocations of this sort serve the purpose of subverting the historical status quo, painting the other side as nothing more than defenders of existing morals and an outdated notion of guilt and atonement. Right-wing terminology and right-wing reinterpretations of normally leftist vocabulary are on the rise. The “subversion of subversion,” as Weiss calls this right-wing conceptual warfare, is now in full swing, and it is not clear at the moment what the antidote might be. Weiss’s eminently readable book aims to “see through” the mechanisms of the war on history being waged by the right and to “defang one of its most effective weapons,” the revisionist reframing of National Socialism. Attacks from the far right are not likely to abate any time soon, meaning it is more important than ever to carry on debunking its disinformation.

Translated by David Burnett

By Christoph Bartmann

Christoph Bartmann was director of the Goethe-Institute in Copenhagen, New York and Warsaw. Today he lives and works in Hamburg as a freelance author and critic.