Children's Books

Anne C. Voorhoeve

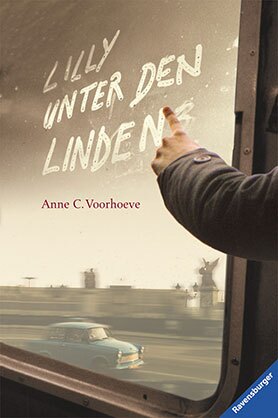

Lilly unter den Linden

[Lilly under the lindens ]

Anne C. Voorhoeve

Lilly unter den Linden

[Lilly under the lindens ]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Chinese (2005 - 2006).

Review

“Those who wish to maintain peace must fight against imp-eria-listic powers. Do you understand that?” “Of course,” said Till cheerfully. “You lot are the imperialists.”

When thirteen-year-old Lily leaves Hamburg in secret after her mother’s death to go and live with her aunt’s family in Jena, she finds herself faced with such confusing slogans as this one in the streets, and with many other initially baffling situations in the daily life of the German Democratic Republic. In her novel for young people, Lilly unter den Linden, Anne Voorhoeve brilliantly succeeds in uniting such disparate subjects as Lilly’s loss of her mother and her adventurous, illicit journey to the GDR with information, suitably presented for her readers’ age, about daily life and its problems in the Socialist part of Germany shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall. She tells the story from the point of view of its protagonist Lilly, now ten years older and, at the age of twenty-three, looking back at that critical period.

Anne C. Voorhoeve does not shrink from writing about feelings that elude sober consideration. This is an emotional but far from sentimental book. Its recurrent themes are parting, loss, jealousy, and the fear of abandonment. The major, central subject of the story, however, is the realization that we must make our own decisions in life, even in extreme personal or political circumstances.

Hamburg, 1988. Lilly is thirteen when her mother dies of cancer at the age of only 34. Her father has already died in a climbing accident years earlier, so she is left with only her mother’s lover, who feels unable to cope with the situation and withdraws as far as possible from maintaining a relationship with her.

At the funeral, Lilly meets her mother’s elder sister Lena, and immediately feels a strong bond with her. But when Lena has to return to her family in Jena, East Germany, after two days in the West, and Lilly faces the threat of placement with a foster family, she feels more desperate than ever.

In a number of flashbacks Lilly remembers the stories told by her mother, who “fled from the Republic” at the age of nineteen to live in West Germany with the man who would be Lilly’s father. Only much later does her daughter understand the complicated and tragic links between her mother’s life and what happened to her aunt.

The facts begin to emerge when Lilly, to everyone’s surprise, turns up in Jena on Christmas Eve. Her fifteen-year-old cousin Katrin slams the door in her face, her aunt and uncle fear trouble with the police, only her younger cousin Till is delighted to meet his new relation from the West. Of necessity, her uncle turns to an old acquaintance in the Stasi (the East German State Security Police) to legalize Lilly’s stay in the GDR.

Gradually, Lilly learns things that dismay her about the past of her mother and her aunt. Not only was her aunt Lena disqualified from continuing in her job as a schoolteacher after her sister fled from East Germany; she was sentenced to three years in prison for helping Lilly’s mother to go to the West. Lena was heavily pregnant at the time, and when she gave birth to Lilly’s cousin Katrin the baby was taken from her immediately and put in a children’s home. Only the help of the family’s hated Stasi acquaintance reunited Katrin’s parents with their daughter when Lena had served her sentence. Lilly can only dimly begin to understand what it costs Lena and her husband Rolf to be obliged to appeal to the Stasi officer for help yet again, this time on Lilly’s behalf.

After a complicated process of naturalization, however, Lilly is finally able to settle in Jena the year before the fall of the Iron Curtain.

There are strong emotions in Anne Voorhoeve’s densely written novel, but she also leaves room for amusing scenes showing the difference between daily life in East and West Germany at the time. When a saleswoman in the Konsum store puts a rotten orange in her bag, Lilly complains and demands a perfect fruit – an attitude that moves some to amusement and others to indignation. Yet if naïveté and ignorance are typical of Lilly’s attitude to the GDR, she is also a self-confident child of the West, shocked by the lying propaganda of the East about life in the Federal Republic. She tries to put her cousin Katrin and Katrin’s friends right:

“… I mean, even if the slogans up in the streets told people here to fight us, I could tell them that we imperialists just wanted peace too.” The three of them tried not to laugh. “Don’t worry, Lilly,” they reassured me. “Nobody looks at those slogans on the posters.”

The book is for young readers of about twelve and upwards, a generation for whom the German Democratic Republic is now only a historical phenomenon. Anne Voorhoeve shows them the everyday life of a system unknown to them as they themselves would probably have experienced it. Readers will be amazed by the absurdity of the propaganda machine and the complications of just going shopping, indignant at the surveillance system, shocked by the sheer extent of state repression. None the less, at the centre of every system are the individual’s actions, the balance between personal knowledge and will in a given set of circumstances. Anne Voorhoeve has written a book about the GDR, morality, and deep feelings, without being either mawkish or biased. We may hope that reading her story will make many young readers ask their parents and teachers questions about this chapter in German history, and help them all to think about it together.

Translated by Anthea Bell