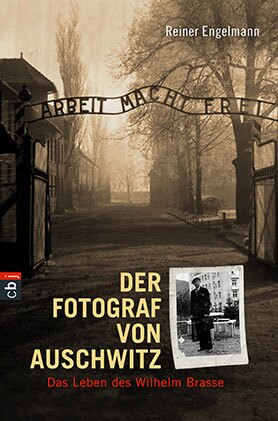

Reiner Engelmann Der Fotograf von Auschwitz. Das Leben des Wilhelm Brasse

Pictures of Horror Reiner Engelmann’s biography of the Auschwitz photographer Wilhelm Brasse

Contributing to the fact that Brasse survived quite a bit longer was—aside from an enormous dose of luck—his skill with a camera. Six months after he was first incarcerated, the trained portrait photographer was assigned to the camp’s so-called ID department. From then on, his main job was to photograph other prisoners for their file: three pictures per person—profile, frontal, and semi-profile with a head covering. Sometimes Brasse shot portraits of more than one hundred people each day. Altogether he must have photographed around 70,000 people. For most of them it was the last photographs of their life.

Reiner Engelmann, who was able to interview Brasse extensively in October 2012, shortly before Brasse’s death, wrote the story of the “Auschwitz photographer” in a small yet remarkable book. In thirty-three short chapters, a panorama of the inhumanities is unfolded. It arouses such a strong feeling of anxiety, because Engelmann keeps his description completely free of sham pathos or false sentimentality. From the perspective of someone who lived through the times, reconstructed in a factual yet empathetic way, the life-threatening presumptions of everyday life in the camp are described. The arbitrariness and brutality of the guards are as vivid as the misanthropic cynicism of the camp doctors. In addition to the newly arrived prisoners, also the subjects of the Nazis’ “medical experiments” stood in front of Brasse’s camera. Sadists in white coats such as Josef Mendele and Carl Clauberg had their racial experiments, hunger experiments, and sterilization massacres documented in the camp’s photo studio.

Brasse was already well aware that what he got to view through his camera lens was only a fraction of the crimes that were committed in the so-called main camp of Auschwitz (Auschwitz I), not to mention the actual exterminatin camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the second half of 1941, the atrocities seemed to have reached a new dimension. Suddenly there were SS men walking around the main camp wearing gas masks. Rumors spread that people were being poisoned systematically and on a large scale with Zyklon B. Up to then the victims were generally hanged, beaten to death, or shot. At some point Brasse’s superior, Ernst Hofmann, gave him new orders in the photo studio: “Brasse, from now on you won’t photograph any more Jews. There’s no sense in that, they’ll die anyway.”

In passing as it were, without any tendency to inappropriately make Brasse into a hero, Engelmann sketches the character of his photographer subject. In order to survive, Brasse had to use his skills as a photographer in the service of the Nazis. Yet his moral compass remained intact. Whenever possible, he tried to help his fellow prisoners, but he was nevertheless overwhelmed by a feeling of powerlessness.

At a crucial moment, however, Brasse refused to obey. In January 1945, when the thunder of Red Army cannons was approaching, the head of the ID department, Oberscharführer Bernhard Walter, turned to him. “Brasse, the Russians are coming.” All documents and photographs were to be destroyed immediately. At first Brasse did in fact throw everything into the stove. But as soon as Walter left the room, he took it all back out. Almost 40,000 of his pictures have remained for posterity as documents against forgetting.

Engelmann’s book contains very few of Brasse’s photographs. But the author’s short, unadorned sentences create vivid pictures of horror in the minds of the readers.

Translated by Allison Brown

By Marianna Lieder

Marianna Lieder works as a freelance journalist and literary critic for publications including the Tagesspiegel, the Stuttgarter Zeitung and Literaturen. She has been an editor at Philosophie Magazin since 2011.

Publisher's Summary

The shocking document of an Auschwitz survivor

When Wilhelm Brasse was deported to the main concentration camp in Auschwitz at the age of 22, he has no idea that as a trained photographer he is to document all the horror of the place. His task is to photograph the camp prisoners. People who shortly afterwards are murdered in the gas chambers. People who are abused by Josef Mengele for "medical research purposes" and whose fear of death is reflected in their faces. Refusal to do this job would have been his own death sentence. When Brasse is to burn all the photos in 1945 he refuses so as not to dIestroy the evidence of the incredible horror. Reiner Engelmann was able to meet Wilhelm Brasse and has written the story of his life. A harrowing document – against oblivion.

• Haunting and disturbing – a documentary report about the

photographer of Auschwitz

• With original photographs from the Auschwitz Museum

(Text: cbj)