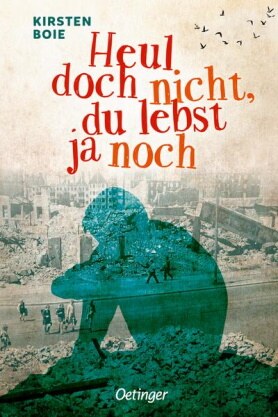

Kirsten Boie

Heul doch nicht, du lebst ja noch

[Don’t Cry, You’re Still Alive]

Friedrich Oetinger Verlag

Hamburg 2022

ISBN 978-3-7512-0163-6

192 Pages

Publisher’s contact details

Translation Grant Programme

Published in Italian with a grant from Litrix.de.