Fiction

Translation Grant Programme

For this title we provide support for translation into the Polish language (2025 - 2027).

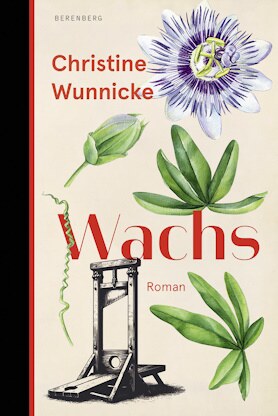

People with special affinities – Christine Wunnicke transports us to 18th-century Paris and the pioneers of anatomy

Christine Wunnicke writes about people with special talents. And she does this in a way that sets off a little dance between their outdatedness and their farsightedness. As we follow her characters, we fall into the spell of this Munich author, who could easily become a protagonist of one of her novels, as for decades she has pursued her own esoteric interests every bit as unerringly as the people she writes about. She spends months conducting research in specialized libraries and journals: about a versifying bon-vivant from the Stuart Restoration, about eighteenth-century cartographers, about a castrato from the Italian Baroque, about an English psychic in the scientific nineteenth century, about a Japanese neurologist investigating hysteria in the time of Sigmund Freud. The list of lifeworlds that spark Wunnicke’s passion is long indeed. But it’s inevitably the loners obsessed with an idea, the mavericks driven by a quest for knowledge that reaches deep into the human soul, with whom the author manages to intrigue her readers.

Her new novel is yet another book that brings incredible things to light. It focuses on Marie Bihéron, once famous but today only familiar to cognoscenti. She lived in Paris in eighteenth century, and her goal in life was to become “the best anatomist of Paris.” The small person who meets us on the first page of Wax approaches the musketeers stationed outside the gates of Paris with the aim of purchasing a corpse: “I have the money on me, I can pay right away, provided it isn’t too expensive, and my mother approves.”

Who can believe such a thing! But then the little person immediately continues: “And I would gladly book a subscription—in the event that it is possible and affordable—for the whole autumn and winter season and all the way until it turns warm again. I would arrange for the first corpse to be picked up tomorrow. Should you have several in storage, I would prefer to have that of a woman or a child, because as you see I am a girl, but I cannot be overly particular. You would need to explain to me all the formalities, especially regarding the burial, and who is responsible for what, and how I should return it once I am finished, because unfortunately I do not know these things.”

So in the year 1733 a girl wants to buy a corpse. She’d heard that they could be found where soldiers were stationed. And so Wunnicke sets off, with a corpse from the musketeers. And soon she sends us, along with her protagonist—first little, soon grown-up, and later in old age—through Paris sprawling wildly through the Enlightenment and the upheavals of the Revolution.

Marie will battle her way through and become a celebrity in her field. Using a special technique she will create wax models that are unrivaled in Europe. Marie is obsessed with the idea of bringing order to the human body, which at the time was orderless and inaccessible, which she did by first dissecting, then dismantling a body and making molds of the individual parts. In this way she created the first true-to-life model of a pregnant woman. She toured half of Europe with her moulages, corresponded with royal families and leading scientists, who supported and promoted her unappetizing but fascinating art.

But before things get that far—at least in Wunnicke’s retelling—Marie’s mother attempts to set the child back on the right path, by setting her up to receive drawing lessons in an art school in Paris’ Marais district. “‘There are professions,’ Madame Bihéron said after a while, that a girl can master. God has given you a talent for drawing. You could learn to draw from nature. That will bring in quite a bit.”

Which brings us to the second personality featured in the novel, namely the world-famous botanical painter Madeleine Basseporte, who operated her workshop in the Jardin Royal, where she also lived—together with Marie Bihéron: “Madeleine Basseporte was a tall beauty, of such rare genus and species that she attracted much gawping, gossip, sighing, and in the worst case, even poems.” Madeleine has no desire to waste her time on such things. Nor does Marie have time for adolescent infatuations. Both have more important things to do.

Because they are mentioned in the same breath by all the luminaries of the Enlightenment, Christine Wunnicke ascribes to them a love affair between equals. She also attributes Marie with a few wonderful dialogues with her prominent neighbor, who actually had been her neighbor in real life. “They weren’t the best neighbors. When she wasn’t screaming at her husband, Madame Diderot was flinging the bobbins around on the pillow with such force it could be heard through the ceiling. She had lately started making lace again because the family was running out of money. Occasionally she screamed at the same time she went about making her lace. Her husband actually took an interest in the lace-making.”

This new novel by Christine Wunnicke is yet another journey through time and ideas to faraway regions. Most of it is factual—the most important part, namely the particular world of ideas and the mental and psychological drama that was bound to entail. And the rest, the invented part, fits perfectly. So while we don’t know anything about Marie Bihéron’s life at the time of the French Revolution, Wunnicke gives us a misshapen old lady stumbling over the rubble of her time.

We learn an amazing amount in this little novel, and we also laugh a lot at the absurd peculiarities of the two female protagonists. To us, looking from today’s perspective, their thoughts and actions seem both the subject of history but also timelessly radical. Every one of Christine Wunnicke’s novels spring from the fact that this human urge for knowledge is at all times constantly and consistently present. Wax, too, has an undertow to which we happily submit. With its extraordinary mix of slapstick, intellectual archeology, and emotional drama, Wax brings us close to the people from the Age of Enlightenment.

Translated by Philip Boehm

By Katharina Teutsch

Katharina Teutsch is a journalist and critic. She writes for newspapers and magazines such as: the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Tagesspiegel, die Zeit, PhilosophieMagazin and for Deutschlandradio Kultur.