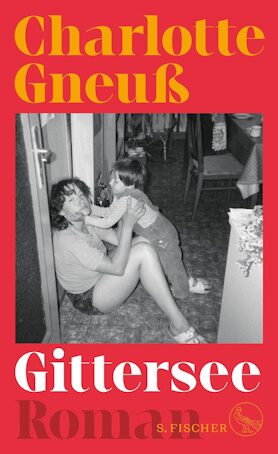

Charlotte Gneuß

Gittersee

[Gittersee]

- S. Fischer Verlag

- Frankfurt am Main 2023

- ISBN 978-3-10-397088-3

- 240 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Translation Grant Programme

Italian rights already sold.

Italian rights already sold.

Sample translations

The Adventure of Betrayal

The GDR disappeared more than thirty years ago, and yet the defunct country is still being written about. A generation of writers with no firsthand experience of this socialist experiment on German soil, who simply know it from family lore or sometimes just from books, has now taken up the pen. One result of this is a new, fresh look at things, a change in perspective. In other words, new stories are emerging, albeit without the authenticity of personal experience to back them up.

Two debut novels of this sort have received abundant, mostly positive attention in the feature pages of 2023. The one is Anne Rabe’s Die Möglichkeit von Glück (The Possibility of Happiness), in which a troubled (eastern) German present is depicted as the result of authoritarian character deformation. The other is Gittersee by Charlotte Gneuß, a book that won both the Jürgen Ponto Foundation as well as the Aspekte literature prizes, arguably the two most distinguished awards for German-language debuts. The question of narrative authenticity has a special East-West dimension in the case of Charlotte Gneuß. The author was born in 1992 in the Swabian town of Ludwigsburg. Her parents and grandparents, whose stories she refers to in the epilog of the novel, lived their lives in the GDR. Her book, in other words, has its roots in real-life experience, which is nevertheless transformed into something completely new and fictional.

Gittersee is a working-class neighborhood on the southwestern outskirts of Dresden. Black coal was mined in the pits under Gittersee since the early nineteenth century, before the extraction of uranium ore began in 1967. Karin, Gneuß’s female protagonist and first-person narrator, is sixteen years old at the start of the novel. She’s still attending school and lives with her grandmother, parents and two-year-old sister in rather straitened circumstances. The year is 1976. Not a great deal is revealed about the adults in the novel, though there are occasional hints at their pasts. Conversations and arguments between the parents indicate that their intellectual talents are not well suited to the daily grind of shiftwork in some factory.

“Gittersee” is a suspenseful story of escape, betrayal and ultimately even murder. The novel relates a wealth of detail, Charlotte Gneuß sticking closely to the thoughts and inner world of her heroine. Karin has a sharp eye, but can’t always see how things hang together. Sometimes she doesn’t want to. Three characters form the center of the novel: Karin, her boyfriend Paul and his friend Rühle. Paul and Rühle once worked together in the mines. Karin is not particularly fond of Rühle, and Rühle’s feelings are mutual. Paul dreams of living the life of an artist – not in Gittersee, but in another world. One day he suggests a weekend outing with Rühle and Karin, a trip to Czechoslovakia on his moped. He shows her the money he’s saved up, now hidden in the tire of his moped. But Karin doesn’t understand, and her parents won’t let her go anyway. A few days later, the secret police show up at her door to question her. There is talk of “fleeing the republic.” Rühle comes back alone and wraps himself in silence about what happened on the outing.

This is the prelude to the novel, an exposition that sets a chain reaction in motion and introduces an almost demonic figure: Wickwalz, a man without a first name who works for the “Stasi” – the East German secret police. Rumors about him begin to spread among Karin and her classmates. Wickwalz flatters Karin, and the reader learns before she does what he wants from her. Today, with historical hindsight, we know that more than ten percent of the unofficial collaborators working for the Stasi were actually underage. “Gittersee” shows us how appealing and seductive it can be when a young person’s thirst for adventure goes hand in hand with naivety and the desire to be of service to a cause. The monstrosity of the betrayal is so skillfully woven into the plot, with its web of everyday life and reality, that it almost seems like the norm.

“Gittersee” sucks the reader in as the novel progresses. It tells of the systemic loss of innocence, complete with a surprising twist at the end and devoid of any false pathos. This is the sound of a new and impressive voice, the voice of a German author who can neither be classified as “East” nor “West.”

Two debut novels of this sort have received abundant, mostly positive attention in the feature pages of 2023. The one is Anne Rabe’s Die Möglichkeit von Glück (The Possibility of Happiness), in which a troubled (eastern) German present is depicted as the result of authoritarian character deformation. The other is Gittersee by Charlotte Gneuß, a book that won both the Jürgen Ponto Foundation as well as the Aspekte literature prizes, arguably the two most distinguished awards for German-language debuts. The question of narrative authenticity has a special East-West dimension in the case of Charlotte Gneuß. The author was born in 1992 in the Swabian town of Ludwigsburg. Her parents and grandparents, whose stories she refers to in the epilog of the novel, lived their lives in the GDR. Her book, in other words, has its roots in real-life experience, which is nevertheless transformed into something completely new and fictional.

Gittersee is a working-class neighborhood on the southwestern outskirts of Dresden. Black coal was mined in the pits under Gittersee since the early nineteenth century, before the extraction of uranium ore began in 1967. Karin, Gneuß’s female protagonist and first-person narrator, is sixteen years old at the start of the novel. She’s still attending school and lives with her grandmother, parents and two-year-old sister in rather straitened circumstances. The year is 1976. Not a great deal is revealed about the adults in the novel, though there are occasional hints at their pasts. Conversations and arguments between the parents indicate that their intellectual talents are not well suited to the daily grind of shiftwork in some factory.

“Gittersee” is a suspenseful story of escape, betrayal and ultimately even murder. The novel relates a wealth of detail, Charlotte Gneuß sticking closely to the thoughts and inner world of her heroine. Karin has a sharp eye, but can’t always see how things hang together. Sometimes she doesn’t want to. Three characters form the center of the novel: Karin, her boyfriend Paul and his friend Rühle. Paul and Rühle once worked together in the mines. Karin is not particularly fond of Rühle, and Rühle’s feelings are mutual. Paul dreams of living the life of an artist – not in Gittersee, but in another world. One day he suggests a weekend outing with Rühle and Karin, a trip to Czechoslovakia on his moped. He shows her the money he’s saved up, now hidden in the tire of his moped. But Karin doesn’t understand, and her parents won’t let her go anyway. A few days later, the secret police show up at her door to question her. There is talk of “fleeing the republic.” Rühle comes back alone and wraps himself in silence about what happened on the outing.

This is the prelude to the novel, an exposition that sets a chain reaction in motion and introduces an almost demonic figure: Wickwalz, a man without a first name who works for the “Stasi” – the East German secret police. Rumors about him begin to spread among Karin and her classmates. Wickwalz flatters Karin, and the reader learns before she does what he wants from her. Today, with historical hindsight, we know that more than ten percent of the unofficial collaborators working for the Stasi were actually underage. “Gittersee” shows us how appealing and seductive it can be when a young person’s thirst for adventure goes hand in hand with naivety and the desire to be of service to a cause. The monstrosity of the betrayal is so skillfully woven into the plot, with its web of everyday life and reality, that it almost seems like the norm.

“Gittersee” sucks the reader in as the novel progresses. It tells of the systemic loss of innocence, complete with a surprising twist at the end and devoid of any false pathos. This is the sound of a new and impressive voice, the voice of a German author who can neither be classified as “East” nor “West.”

By Christoph Schröder

Christoph Schröder, born in 1973, works as a freelance author and critic for Deutschlandfunk, Die Zeit and Süddeutsche Zeitung among other media outlets.