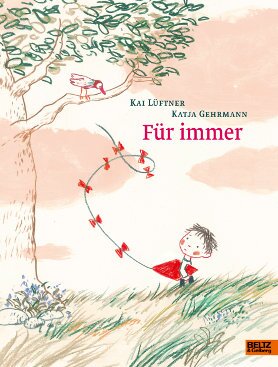

Kai LüftnerKatja Gehrmann

Für immer

[For ever]

- Beltz & Gelberg Verlag

- Weinheim/ Basel 2013

- ISBN 978-3-407-79546-5

- 32 Pages

- 4 Suitable for age 5 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Kai Lüftner

Für immer

[For ever]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Russian (2012 - 2014).

Sample translations

Review

There are already books aplenty for children and young adults about death. The deaths of grandparents, parents, siblings, friends have all given rise to minor literary masterpieces, some even depicting the death of young people as experienced by those most directly affected, and recounted in first-person narrative form. One only has to think of Sally Nicholls’ Ways to Live Forever or John Green’s The Fault in our Stars.

Books such as these, however, do presuppose that the reader is capable of responding in quite sophisticated ways to the issues raised. How, on the other hand, does one present them to young children who haven’t even learnt to read yet without unsettling or frightening them, or without steering them straight into the realm of other-worldly explanations? Twenty years ago Roberto Piumini’s story Mattia e il nonno — Mattie and Grandpa, published in German as Matti und der Grossvater, with illustrations by Quint Buchholz — offered a wonderful new departure by depicting an imaginary walk undertaken by the grandfather and his grandson, in the course of which the old man gradually gets smaller and smaller until he ends up perching on the nose of the child, who then breathes him in. The grandfather is thus embodied in his grandson ‘for ever’ and becomes part of his fresh young life.

Kai Lüftner and Katja Gehrmann’s picture book is entitled For ever, and, addressing itself to very young children, it echoes Piumini’s book in its readily understandable and comforting approach to the topic of ‘how to cope with life after the death of a loved one’. In the book, little Egon, who looks about five, recounts the story of his daddy’s death, and at the end the writer, Kai Lüftner, has him declare ‘ Dad’s always with me. Not just in my favourite photo. Not just in my heart. I’m Dad myself. A little bit of me anyway. For ever.’

Whilst he grieves for his daddy, who ‘had something nasty in his chest’, Egon is a sturdy little chap who strides on through everyday life with his eyes wide open and the flame-red kite that he had made with his daddy tucked permanently beneath his arm, even though inwardly he’s still in a state of utter confusion. He pours out his impressions and experiences, his thoughts and his fears, as if the reader were his best friend walking along by his side.

We thus discover what it means to find yourself bereft, to lose your daddy for ever, while those around you behave as if nothing had happened — except, of course, for those already acquainted with Egon and his mother: the grinners, who are determined to cheer them up; the whisperers, who look at them in a funny way; not least the tongue-tied, who can’t manage even a single comforting word. Egon has difficulties with all of them — especially with those who he thought might simply hold him by the hand without constantly telling him how much they pity him. Egon’s narrative is one part of the story. Katja Gehrmann’s illustrations are the other — and they are enchanting in their plain, unaffected depiction of Egon’s thoughts and feelings. The sense of melancholy is tinged with lightness, indeed with a flicker of hope. Despite all the figures stricken by grief or lost for words, despite the ever present question of how to carry on in the face of such a loss, there are pointers to a more hopeful future — a squirrel surveying the scene with cheerful curiosity, a dog tugging energetically at its lead.

Katja Gehrmann renders these various moods within and around Egon very effectively through her conspicuously fresh and lively use of wax crayon. Backgrounds are merely touched in, as if everything — clouds and meadows, roads and houses — were but fleeting phenomena subject to the vagaries of nature. Even the endpapers are a sheer delight to the eye with their pinboard-style evocation of the family’s life in happier days. The figures in the drawings are simple, endearingly cartoon-like creatures, most notably Egon with his red cheeks, his tousled hair and his beloved kite tucked under his arm, but also the youngsters frolicking in the kindergarten — especially the friendly little curlyhead in a striped jumper who heads straight for Egon without giving it a thought, just to play with him and have lots of fun.

And look: the wind has caught the kite. It soars higher and higher, the cheeks of the two boys glow with pleasure — and for the first time a smile appears on the faces of the watching adults. This sudden moment of hope, of life continuing despite everything, could not have been captured more simply or more beautifully.

Books such as these, however, do presuppose that the reader is capable of responding in quite sophisticated ways to the issues raised. How, on the other hand, does one present them to young children who haven’t even learnt to read yet without unsettling or frightening them, or without steering them straight into the realm of other-worldly explanations? Twenty years ago Roberto Piumini’s story Mattia e il nonno — Mattie and Grandpa, published in German as Matti und der Grossvater, with illustrations by Quint Buchholz — offered a wonderful new departure by depicting an imaginary walk undertaken by the grandfather and his grandson, in the course of which the old man gradually gets smaller and smaller until he ends up perching on the nose of the child, who then breathes him in. The grandfather is thus embodied in his grandson ‘for ever’ and becomes part of his fresh young life.

Kai Lüftner and Katja Gehrmann’s picture book is entitled For ever, and, addressing itself to very young children, it echoes Piumini’s book in its readily understandable and comforting approach to the topic of ‘how to cope with life after the death of a loved one’. In the book, little Egon, who looks about five, recounts the story of his daddy’s death, and at the end the writer, Kai Lüftner, has him declare ‘ Dad’s always with me. Not just in my favourite photo. Not just in my heart. I’m Dad myself. A little bit of me anyway. For ever.’

Whilst he grieves for his daddy, who ‘had something nasty in his chest’, Egon is a sturdy little chap who strides on through everyday life with his eyes wide open and the flame-red kite that he had made with his daddy tucked permanently beneath his arm, even though inwardly he’s still in a state of utter confusion. He pours out his impressions and experiences, his thoughts and his fears, as if the reader were his best friend walking along by his side.

We thus discover what it means to find yourself bereft, to lose your daddy for ever, while those around you behave as if nothing had happened — except, of course, for those already acquainted with Egon and his mother: the grinners, who are determined to cheer them up; the whisperers, who look at them in a funny way; not least the tongue-tied, who can’t manage even a single comforting word. Egon has difficulties with all of them — especially with those who he thought might simply hold him by the hand without constantly telling him how much they pity him. Egon’s narrative is one part of the story. Katja Gehrmann’s illustrations are the other — and they are enchanting in their plain, unaffected depiction of Egon’s thoughts and feelings. The sense of melancholy is tinged with lightness, indeed with a flicker of hope. Despite all the figures stricken by grief or lost for words, despite the ever present question of how to carry on in the face of such a loss, there are pointers to a more hopeful future — a squirrel surveying the scene with cheerful curiosity, a dog tugging energetically at its lead.

Katja Gehrmann renders these various moods within and around Egon very effectively through her conspicuously fresh and lively use of wax crayon. Backgrounds are merely touched in, as if everything — clouds and meadows, roads and houses — were but fleeting phenomena subject to the vagaries of nature. Even the endpapers are a sheer delight to the eye with their pinboard-style evocation of the family’s life in happier days. The figures in the drawings are simple, endearingly cartoon-like creatures, most notably Egon with his red cheeks, his tousled hair and his beloved kite tucked under his arm, but also the youngsters frolicking in the kindergarten — especially the friendly little curlyhead in a striped jumper who heads straight for Egon without giving it a thought, just to play with him and have lots of fun.

And look: the wind has caught the kite. It soars higher and higher, the cheeks of the two boys glow with pleasure — and for the first time a smile appears on the faces of the watching adults. This sudden moment of hope, of life continuing despite everything, could not have been captured more simply or more beautifully.

Translated by John Reddick

By Siggi Seuß

Siggi Seuß, freelance journalist, radio script writer and translator, has been writing reviews of books for children and young people for many years.