Bernd Schuh

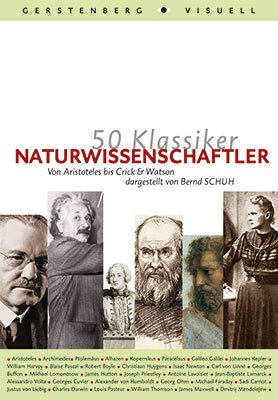

50 Klassiker: Naturwissenschaftler. Von Aristoteles bis Crick & Watson

[50 Classics: Scientists. From Aristotle to Crick & Watson]

- Gerstenberg Verlag

- Hildesheim 2006

- ISBN 3-8067-2550-0

- 264 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Bernd Schuh

50 Klassiker: Naturwissenschaftler. Von Aristoteles bis Crick & Watson

[50 Classics: Scientists. From Aristotle to Crick & Watson]

Sample translations

Review

Roughly thirty books covering a wide range of subjects have already been published in Gerstenberg Verlag’s “50 Classics” series, such as 50 Classics: Philosophers, Couples, and Operas. Bernd Schuh, who was awarded the German Youth Literature Prize in 2002 in the area of non-fiction for his Visuelles Lexikon der Umwelt (Visual Lexicon of the Environment), has now presented a survey of developments in the natural sciences since Aristotle. Although fifty brief portrayals can offer only a few important examples in a broad spectrum of disciplines, Schuh’s book has managed two things: first, it is excellently suited as an easy-to-understand reference work, even for readers not well versed in the natural sciences; second, it presents the insights and new approaches of each scientist not only in a scientific context, but always also within the relevant social context, thereby focusing on the dynamic relationship between scientific knowledge and the prevailing worldview of the time. Schuh illustrates that the scientists and their promoters were driven, not only by a thirst for knowledge, but also by real ideological and material interests. This approach makes it possible for the chronological arrangement of the fifty biographies of the scientists to offer at the same time a short survey of the history of science.

The book’s layout plays an important role and follows the style concept of the entire series: The texts are not dense blocks of solid print, but are graphically loosened up with numerous illustrations such as portraits and photographs of laboratories or special tools. Each chapter is comprised of a 3–4-page description of the respective scientist’s main area of research and most significant findings or theories. Schuh finds a fitting framework for each biography, whether anecdotal with quotations or including commentaries of famous contemporaries or a description of special research series or unusual methodology. Each presentation is rounded out by a compact biography including background, education, family life, and career, and supplemented by the headings “Interesting Facts,” “Recommendations” (with tips for further reading, links, and interesting museums to visit), and “To the Point.”

Bernd Schuh begins his presentation in classical antiquity, with Aristotle, Archimedes, and Ptolemy, covering their research areas of describing nature, mathematics and physics, and astronomy. This covers a large segment of the basic sciences from which all highly sophisticated disciplines later developed. But “science in the service of those in power” is also discussed at the outset, when Schuh describes how Archimedes used the newly discovered laws of mechanics to build more effective military equipment. The book then jumps around eight hundred years, bypassing Europe’s early Middle Ages, which were Dark Ages not only from a science perspective. Alhazen (al-Haytham), the “father of optics,” worked in many areas including the refraction of light when moving from one medium to another and how the human eye functions. He serves as one representative among the many influential scientists in the Arab world at that time. After another four centuries went by without any remarkable new insights in western science, Copernicus and Paracelsus appeared on the scene as the first “modern” scientists. They were interested primarily in astronomy and medicine, as these areas were most important for the intellectual and physical well-being of people in Europe from the late fifteenth to the early seventeenth centuries. Biology (though it did not receive that name until much later), physics, chemistry (in contrast to its darker sister, alchemy), and mathematics gradually developed into independent scientific disciplines starting in the early seventeenth century.

As the sciences became more differentiated, the number of new discoveries of course climbed sharply. Scientists in the seventeenth century were especially active in the fields of astronomy, mechanical physics, and rudimentary anatomy. In the eighteenth century, the main additions were biology and chemistry. The primary driving force at that time appears to have been a wish to understand the world and its phenomena, but a desire to utilize and modify these phenomena for the good of humanity did not develop until later. That first came with the discovery and use of electricity by Volta, Ohm, and Faraday, or with Liebig, when there was increased interest, for example, in using chemical analyses in agriculture. The names Pasteur, Koch, and Roentgen are important to mention as regards medical advances. The scientific disciplines were no longer distinct from one another; instead, they were interrelated and overlapping, and one area of science profited from the findings of another.

Providing portraits of all important natural scientists of the twentieth century would have gone beyond the scope of Schuh’s book, if he did not stop at the discoverers of the double helix structure of DNA, Crick and Watson. Because research has become much more sophisticated and complex, making it difficult to offer an easily understood explanation of research in such areas as theoretical physics, it makes sense that only the first half of the twentieth century was included. The introduction of the concept of quantum physics by Max Planck and the resulting possibilities for the development of theoretical physics marked only the beginning, and nuclear science and genetics are just two of the crucial fields of research that continue to carry as yet indeterminable risks and potential for humanity.

Bernd Schuh’s book is very informative without being dry, and it is exciting without being superficial. The author is extremely successful in arousing interest in a wide range of subjects, and his practical tips for reading and “surfing” also help to stimulate readers to further their knowledge. The book’s appealing design makes it outstandingly suited as a reference work, but readers will most likely read it right through from beginning to end.

The book’s layout plays an important role and follows the style concept of the entire series: The texts are not dense blocks of solid print, but are graphically loosened up with numerous illustrations such as portraits and photographs of laboratories or special tools. Each chapter is comprised of a 3–4-page description of the respective scientist’s main area of research and most significant findings or theories. Schuh finds a fitting framework for each biography, whether anecdotal with quotations or including commentaries of famous contemporaries or a description of special research series or unusual methodology. Each presentation is rounded out by a compact biography including background, education, family life, and career, and supplemented by the headings “Interesting Facts,” “Recommendations” (with tips for further reading, links, and interesting museums to visit), and “To the Point.”

Bernd Schuh begins his presentation in classical antiquity, with Aristotle, Archimedes, and Ptolemy, covering their research areas of describing nature, mathematics and physics, and astronomy. This covers a large segment of the basic sciences from which all highly sophisticated disciplines later developed. But “science in the service of those in power” is also discussed at the outset, when Schuh describes how Archimedes used the newly discovered laws of mechanics to build more effective military equipment. The book then jumps around eight hundred years, bypassing Europe’s early Middle Ages, which were Dark Ages not only from a science perspective. Alhazen (al-Haytham), the “father of optics,” worked in many areas including the refraction of light when moving from one medium to another and how the human eye functions. He serves as one representative among the many influential scientists in the Arab world at that time. After another four centuries went by without any remarkable new insights in western science, Copernicus and Paracelsus appeared on the scene as the first “modern” scientists. They were interested primarily in astronomy and medicine, as these areas were most important for the intellectual and physical well-being of people in Europe from the late fifteenth to the early seventeenth centuries. Biology (though it did not receive that name until much later), physics, chemistry (in contrast to its darker sister, alchemy), and mathematics gradually developed into independent scientific disciplines starting in the early seventeenth century.

As the sciences became more differentiated, the number of new discoveries of course climbed sharply. Scientists in the seventeenth century were especially active in the fields of astronomy, mechanical physics, and rudimentary anatomy. In the eighteenth century, the main additions were biology and chemistry. The primary driving force at that time appears to have been a wish to understand the world and its phenomena, but a desire to utilize and modify these phenomena for the good of humanity did not develop until later. That first came with the discovery and use of electricity by Volta, Ohm, and Faraday, or with Liebig, when there was increased interest, for example, in using chemical analyses in agriculture. The names Pasteur, Koch, and Roentgen are important to mention as regards medical advances. The scientific disciplines were no longer distinct from one another; instead, they were interrelated and overlapping, and one area of science profited from the findings of another.

Providing portraits of all important natural scientists of the twentieth century would have gone beyond the scope of Schuh’s book, if he did not stop at the discoverers of the double helix structure of DNA, Crick and Watson. Because research has become much more sophisticated and complex, making it difficult to offer an easily understood explanation of research in such areas as theoretical physics, it makes sense that only the first half of the twentieth century was included. The introduction of the concept of quantum physics by Max Planck and the resulting possibilities for the development of theoretical physics marked only the beginning, and nuclear science and genetics are just two of the crucial fields of research that continue to carry as yet indeterminable risks and potential for humanity.

Bernd Schuh’s book is very informative without being dry, and it is exciting without being superficial. The author is extremely successful in arousing interest in a wide range of subjects, and his practical tips for reading and “surfing” also help to stimulate readers to further their knowledge. The book’s appealing design makes it outstandingly suited as a reference work, but readers will most likely read it right through from beginning to end.

Translated by Allison Brown

By Heike Friesel