New novels with new features

Is “Broken German” better than German Introspection?

By Michael Schmitt

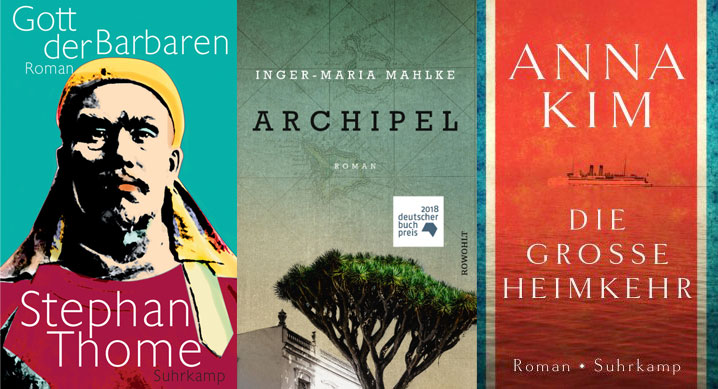

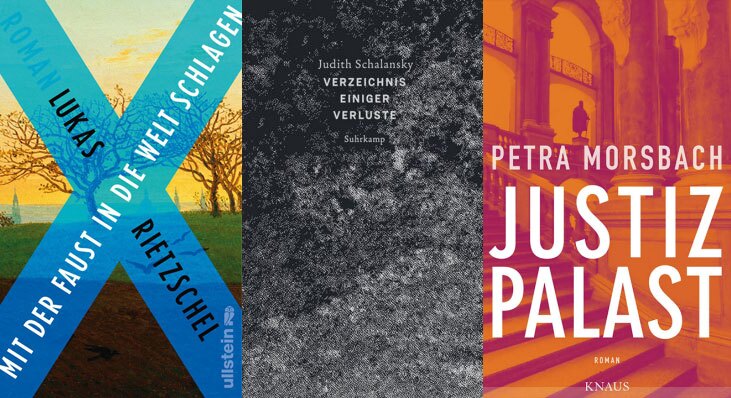

When the shortlist for the 2018 German Book Prize was disclosed in September 2018, it was said that the state of the world seemed to be preying on the minds of German-language writers. A perfect example of this was Inger Maria Mahlke’s novel, “Archipel” (Rowohlt), which won the book prize in October 2018. The book revolves around the history of the island Tenerife, but is told in reverse as a kind of archaeological excavation that digs deeper and deeper across more than a hundred years. The small cosmos of world and regional history starts with the crisis in Spain in 2015 then moves on to the Franco regime and ends in the year 1919. Rich in detail, but more conventionally written, Stephan Thome’s “Gott der Barbaren” (Suhrkamp) leads the reader straight into the middle of the uprisings in China in the middle of the 19th century. In the novel “Der Vogelgott” (Jung und Jung), Susanne Röckel, writes in the style of Gothic novel, about a culturally and scientifically interested family that gets entangled in the cruel mythology of archaic communities. In 2017, Anna Kim relayed the little-known story of Korea in her novel, “Die große Heimkehr” (Suhrkamp). As a starting point for imaginative journeys into history and remote worlds, Judith Schalansky makes use of historical or scientific facts and curiosities in her book “Verzeichnis einiger Verluste” (Suhrkamp, 2018), which was awarded the Wilhelm Raabe Literature Prize.

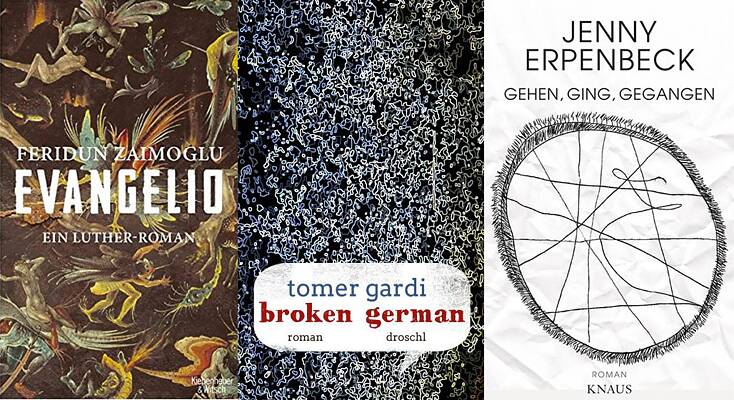

Focusing on the world at large, as well as a constant preoccupation with one’s own origins, has been the outcome of years of “immigration” into German literature by authors who, for example, came to Germany, Austria or Switzerland as migrants in the first or second generation. Feridun Zaimoglu, who recently published “Evangelio: ein Luther-Roman” (Kiepenheuer und Witsch, 2017) (slotted for 2019: “Die Geschichte der Frau”, Kiepenheuer & Witsch) exemplifies this trend as does the Iraqi-born Abbas Khider, who circles around his escape and the conditions for his admission to Germany with a drastic sense of humor (slotted for spring 2019: “Deutsch für alle. Das endgültige Lehrbuch“, Hanser).

This trend has been particularly evident in the last few years by the televised Ingeborg Bachmann competition in Klagenfurt, which has captured the attention of the media.

The most recent winners have been texts written by authors who were not born in German-speaking countries, such as the writer and activist Sharon Dodua Otoo’s short story “Herr Gröttrup setzt sich hin,” 2016; or in 2018, the Ukrainian-born and Vienna-based author and journalist Tanja Maljartschuk, whose new novel about an unfortunate Ukrainian politician will be published in spring 2019 (“Blauwal der Erinnerung”, Kiepenheuer & Witsch). Tomer Gardi, who was born in Israel, also caused a sensation in 2016 with the text “Broken German” not only because it exaggeratedly portrays the experiences of immigrants, but also, to a certain extent, because it dismembers the German language into its individual parts and imparted it with an entirely new sound.

The writer and translator Natascha Wodin has also written in an unusually vivid manner about the fate of immigrants in her two most recent books: her mother’s life story set in her hometown Mariupol in Crimea (“Sie kam aus Mariupol”, Rowohlt 2016), and her father’s life story (“Irgendwo in diesem Dunkel”, Rowohlt, 2018), which deals with him growing up in the Soviet Union. These stories deal with the repercussions of constantly fleeing from one’s home country as well as the losses incurred from 1917 to the period after the Second World War; and ends in a life lived at the margins as a Russian-German in a Franconian small town at the start of Germany’s economic miracle.

Often thematically anchored in the everyday life of a younger generation and formally shaped by the short forms and oral presentations of reading stages and slam poetry competitions, the programs of relatively young publishers (Voland & Quist, Satyr, Mairisch, etc.) have also been very successful. A large number of younger writers, such as the poet Nora Gomringer or the writers Finn-Ole Heinrich and Marc Uwe Kling, have also made a name for themselves beyond the traditional distribution channels of German-language literature, turning to new digital forums ranging from e-publishing to Youtube channels. But it has often been only a first step towards a career that has led back to the traditional literary market.

Michael Schmitt is literature editor at 3sat-Kulturzeit and freelance critic for NZZ, SZ and Deutschlandfunk. His work focuses on German-language and Anglo-American literature as well as children's and young adult literature. Michael Schmitt was a member of the Litrix jury from 2015-2017.

Translated by Zaia Alexander