Gero von Randow

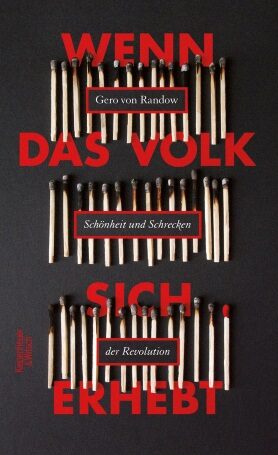

Wenn das Volk sich erhebt. Schönheit und Schrecken der Revolution

[When the People Rise. The Allure and Atrocity of Revolution]

- Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag

- Cologne 2017

- ISBN 978-3-462-04876-6

- 313 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Gero von Randow

Wenn das Volk sich erhebt. Schönheit und Schrecken der Revolution

[When the People Rise. The Allure and Atrocity of Revolution]

Sample translations

Once upon a time there was... a revolution?

It was von Randow himself, now a journalist, who at the age of 14 experienced his political baptism on that day: ‘I suddenly saw the world with different eyes’, he says today. ‘From that moment onwards the existing state of things seemed to me to be a purely provisional phase, a time of transition. Each and every conflict with the authorities was to my way of thinking a battle against conditions that were unjust not merely in the particular, but in their entirety.’ It is accordingly only logical that von Randow should put this childhood memory right at the start of his book, entitled Wenn sich das Volk erhebt. Schönheit und Schrecken der Revolution [When the people rise up. The beauty and the terror of revolution].

50 years since the killing of Ohnesorg, 100 years since the events of 1917: this dual anniversary would be sufficient on its own to justify the publication of this book about revolution. The author discusses the Russian revolution, of course - but he also discusses those that have occurred since the French Revolution in Britain, America and Latin America, and he reminds us about Germany’s soviet republics (Räterepubliken), the Cultural Revolution in China, the collapse of the Berlin Wall, and the Arab Spring. And in doing this, he doesn’t lose sight of the blueprints for revolution offered by the history of ancient Rome. Extremely learned though it is, however, his book is by no means merely a dry academic tome on the global history of revolt: with great narrative élan it proposes a typology of rebellion and its key protagonist, the revolutionary. For what especially interests the author is the process whereby individuals transcend the specificity of the present moment and enter the great nexus of history, and the process whereby such transcendences retrospectively affect the genealogical nexus.

‘The bridges that lead to the past are short’, says von Randow. ‘Memories migrate across them into the present. But these memories are kept alive not only in academic seminars, in organisations, in literature, but also within families, and in consequence they pervade not only people’s rational consciousness but also their emotional worlds. The messages conveyed by these memories can be variously perceived: some might say "Such bad times, the old days!", while others think "People shouldn’t just put up with their lot!", and yet others take the view that "There was real hope then for a better world." ’

Hope? Gero von Randow ultimately leaves the question open as to how much revolution the world - or, as we should perhaps rather say, capitalism - actually needs to experience. He points out that Lenin’s embalmed body has outlasted Leninism. ‘Capitalism preserves its opponents. It can even make money out of them. People do occasionally try to storm Lenin’s mausoleum, in order - as they say - to wake him from his sleep. The authorities treat them as insane.’

One question thus remains open at the conclusion of the book: are we to suppose - may we even suppose - that the concept of revolution has by no means fallen into oblivion and that the prevailing circumstances are therefore still capable of being overthrown? Or are we to adopt the position of the ex-communist historian François Furet: ‘We are thus damned to continue living in the world in which we now live’? Gero von Randow is honest enough to leave this question in the balance.

Translated by John Reddick

By Ronald Düker

Ronald Düker is a cultural scientist and author for the feature section of the newspaper DIE ZEIT. He lives in Berlin.

Publisher's Summary

The age of revolutions isn’t over

Why is it such a special – downright exalted – moment when the people rise up, on Tahrir Square in Cairo or on the Maidan in Kiev? Why do revolutions thrill us, even when we know that their actual aims won’t be reached, will be quelled or betrayed – usually by the revolutionaries themselves? In this rivetingly written, very personal book, von Randow describes his experience of revolutions and examines the question of whether they are still a viable model for the future. His answers are extremely topical and surprising.

A hundred years ago, the October Revolution prevailed in Russia. And 50 years ago an entire generation of young people believed that the age of revolutions was once again at hand. What remains of all this? Nothing but resignation? And what is a revolution anyway? In 2011, the author was given an object lesson when he became an eyewitness to the Tunisian Revolution. His thesis: revolutions arrive unexpectedly. And yet, it is possible to discern certain recurring patterns.

The author turns his attention to the American continent, Western and Eastern Europe, Africa and Asia. He covers centuries, from the rebellious slaves in ancient times to the revolutionaries of 1789 and the international communist movement to present-day rebellions – always in search of facts and ideas that might shed light on the most unusual, multifaceted phenomenon in history: revolution.

"Revolutions are wonderful, terrible, as great in the good they contain as the bad. Through them, the ideal of freedom steps onto the stage of history. An exalted moment. Sometimes short-lived. Revolutions create something irrevocable. Even when the counterrevolution prevails."

(Text: Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag)