Judith Schalansky

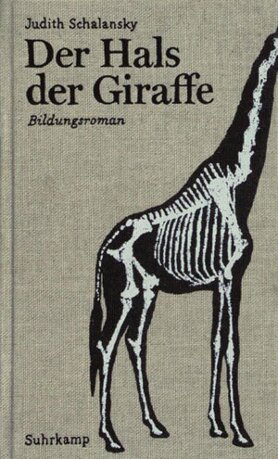

Der Hals der Giraffe

[The giraffe's neck]

- Suhrkamp Verlag

- Berlin 2011

- ISBN 978-3-518-42177-2

- 222 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Published in Russian with a grant from Litrix.de.

Sample translations

Review

The focus of Judith Schalansky’s new novel, "Der Hals der Giraffe" [The giraffe’s neck], is obvious from the very first paragraph, though we can’t quite figure out its meaning yet. The protagonist, a biology teacher, blurts out orders to the students of her ever-shrinking class like an army sergeant. They should open their textbooks to page seven, “and then they started on ecological balances, eco-systems, the interdependencies and interrelations between species, between living creatures and their environment, the effective organization of community and space.” At the Charles Darwin School, located in Mecklenburg-Pomerania, the laws of evolution are recited with enthusiasm: "eating and being eaten. It was wonderful."

In reality, it is all rather tragic. Though natural selection and mutation might offer elegant biological processes for preserving the species, in human society it creates ethical problems. What do you do with the weaklings ("parasites on the healthy body of the class")? Must one feed them all? ("The later you left getting rid of a failure, the more dangerous he became.") Can it be possible that social Darwinism, in terms of population questions, has been unjustly discredited?

Inge Lohmark isn’t concerned about moral misgivings; the relentless evolution continues to take its toll on the sluggish region, the school, and her private life: the Darwin High School is scheduled to close; unemployment is on the rise, a declining population, and scarcity of young people. Judith Schalansky, who was born and raised in Greifswald, knows the world-weary discourse on civilization that developed in parts of eastern Germany since 1989.

And even if Inge Lohmark is prone to brutal biologistic platitudes, we empathize with this haggard ideologue. She is merely trying to plug and pacify, where the need for anything to be plugged and pacified had long ceased to exist. In fact, it seems that everything, absolutely everything, opposes the course of nature which has brought forth an unrivaled food-friendly giraffe’s neck. Where an entire region has halted reproduction, instead of increasing its assets; where her own daughter has run off to America with no hope of begetting offspring; and where her husband has transferred his libidinal energy to raising ostriches, this is the point when one must counter defeat with cool reason and a stiff upper lip.

Inge Lohmark’s students are on the receiving end of it: “Her pupils had no right to speak and no opportunity to choose. No one had a choice. There was natural selection and that was that.” But in the sphere of human relations this is hardly something to be taken for granted: “There was no order. Order had to be created.”

One could endlessly quote from the stream-of-consciousness thoughts of this brilliant, disillusioned protagonist, but Judith Schalansky isn’t interested in merely serving up a drastic case study. The book’s subtitle is "Bildungsroman", (coming-of-age or education novel) and raises the question whether education is capable of stopping the course of nature, demographics, or the natural pecking order. Indeed, humans have a problem: "This far too large brain; a reservoir of knowledge, is oversized like the antlers of the giant deer from the ice age."

There is, alas, hope that imperfection can be useful for something – at the precise moment when emotions come into play and the laws of nature are momentarily suspended. "Yes, there were so many uncontrollable factors," such as the love for a pupil, which awakens in Inge Lohmark an unknown sadistic (and therefore "unnatural") instinct – in her of all people, a person who up to that point had considered love to be a "seemingly airtight alibi for a sick symbiosis."

Schalansky’s book is unique, not only because it relentlessly explores the limits of human frustration, but also because of its visual design. Even the book as a medium is an endangered species in terms of its battle against the digital world. But this author, who was formerly a professional graphic designer and typographer, had designed in 2009, the “Atlas of remote islands,” which won a prestigious design award and is considered a collector’s item, also designed “The giraffe’s neck.”

The slim volume is covered with an elegant linen lining. It depicts three days in the life of a teacher whose tirades are complemented by beautiful images of bats, jellyfish, and sea cows. Thus, we learn that the common stinging jellyfish not only possesses a rhizome-like brain replacement, but the creature can also be studied in all its glory. The amused reader can take a look from two sides and decide for him or herself whether the jellyfish, with its network of nerves, hasn’t won the jackpot in the era of multitasking.

Judith Schalansky has earned effusive praise from critics for her idealism, her humor, and for the multifaceted intelligence of her little Bildungsroman and picture book. Rightly so.

In reality, it is all rather tragic. Though natural selection and mutation might offer elegant biological processes for preserving the species, in human society it creates ethical problems. What do you do with the weaklings ("parasites on the healthy body of the class")? Must one feed them all? ("The later you left getting rid of a failure, the more dangerous he became.") Can it be possible that social Darwinism, in terms of population questions, has been unjustly discredited?

Inge Lohmark isn’t concerned about moral misgivings; the relentless evolution continues to take its toll on the sluggish region, the school, and her private life: the Darwin High School is scheduled to close; unemployment is on the rise, a declining population, and scarcity of young people. Judith Schalansky, who was born and raised in Greifswald, knows the world-weary discourse on civilization that developed in parts of eastern Germany since 1989.

And even if Inge Lohmark is prone to brutal biologistic platitudes, we empathize with this haggard ideologue. She is merely trying to plug and pacify, where the need for anything to be plugged and pacified had long ceased to exist. In fact, it seems that everything, absolutely everything, opposes the course of nature which has brought forth an unrivaled food-friendly giraffe’s neck. Where an entire region has halted reproduction, instead of increasing its assets; where her own daughter has run off to America with no hope of begetting offspring; and where her husband has transferred his libidinal energy to raising ostriches, this is the point when one must counter defeat with cool reason and a stiff upper lip.

Inge Lohmark’s students are on the receiving end of it: “Her pupils had no right to speak and no opportunity to choose. No one had a choice. There was natural selection and that was that.” But in the sphere of human relations this is hardly something to be taken for granted: “There was no order. Order had to be created.”

One could endlessly quote from the stream-of-consciousness thoughts of this brilliant, disillusioned protagonist, but Judith Schalansky isn’t interested in merely serving up a drastic case study. The book’s subtitle is "Bildungsroman", (coming-of-age or education novel) and raises the question whether education is capable of stopping the course of nature, demographics, or the natural pecking order. Indeed, humans have a problem: "This far too large brain; a reservoir of knowledge, is oversized like the antlers of the giant deer from the ice age."

There is, alas, hope that imperfection can be useful for something – at the precise moment when emotions come into play and the laws of nature are momentarily suspended. "Yes, there were so many uncontrollable factors," such as the love for a pupil, which awakens in Inge Lohmark an unknown sadistic (and therefore "unnatural") instinct – in her of all people, a person who up to that point had considered love to be a "seemingly airtight alibi for a sick symbiosis."

Schalansky’s book is unique, not only because it relentlessly explores the limits of human frustration, but also because of its visual design. Even the book as a medium is an endangered species in terms of its battle against the digital world. But this author, who was formerly a professional graphic designer and typographer, had designed in 2009, the “Atlas of remote islands,” which won a prestigious design award and is considered a collector’s item, also designed “The giraffe’s neck.”

The slim volume is covered with an elegant linen lining. It depicts three days in the life of a teacher whose tirades are complemented by beautiful images of bats, jellyfish, and sea cows. Thus, we learn that the common stinging jellyfish not only possesses a rhizome-like brain replacement, but the creature can also be studied in all its glory. The amused reader can take a look from two sides and decide for him or herself whether the jellyfish, with its network of nerves, hasn’t won the jackpot in the era of multitasking.

Judith Schalansky has earned effusive praise from critics for her idealism, her humor, and for the multifaceted intelligence of her little Bildungsroman and picture book. Rightly so.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

By Katharina Teutsch

Katharina Teutsch is a journalist and critic. She writes for newspapers and magazines such as: the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Tagesspiegel, die Zeit, PhilosophieMagazin and for Deutschlandradio Kultur.