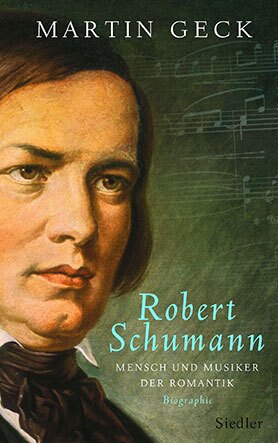

Martin Geck

Robert Schumann

[Robert Schumann, the Romantic: Musician and Man of his Time]

- Siedler Verlag

- München 2010

- ISBN 978-3-88680-897-7

- 319 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Martin Geck

Robert Schumann

[Robert Schumann, the Romantic: Musician and Man of his Time]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Spanish: Argentina (2009 - 2011).

Sample translations

Review

Among the great composers of the 19th century, Robert Schumann is the very portrait of the tragic Romantic artist and introverted man of sorrows; a character riddled with contradictions, his life was an emotional roller coaster between creative highs and profound identity crises, his early end marked by loneliness and mental derangement.

Schumann passed away on the afternoon of July 29, 1856. A man of a mere 46 years, he met his death in the Endenich Sanitorium. Two years prior to that – following a failed suicide attempt and suffering from severe auditory hallucinations – he had given his consent to be committed to this psychiatric institution in greater Bonn. “Melancholia with delusions” reads the diagnosis placed in his medical records at the time; after Schumann’s death, this annotation was also supplemented with the term “Paralysia.” The question as to whether these symptoms might be construed as long-term effects of syphilis, which Schumann is said to have acquired as a young man, is still the subject of debate today.

The diagnosis given the composer Schumann, born in Zwickau in 1810, has retained its mystifying inscrutability in spite of the wealth of source materials available to us; and this vague medical diagnosis became – in equally full measure – a disaster for the composer posthumously as ensuing generations projected it onto his music. Conductor Giuseppe Sinopoli, for example, has described Schumann’s second symphony in C major as “composed-out psychosis”; for composer Dieter Schnebel, the “Dichterliebe” lieder cycle, written in 1840 during Schumann’s first highly seminal creative period, conveys a “deeply rooted melancholic resignation, one crippling his will to live.”

Indeed, Schumann’s last orchestral work, the Violin Concerto in D minor, though kept from the public by the trustees of his estate until 1937, has won a permanent place in the repertoire of numerous violin virtuosos; yet this piece, as one of the late works by the great poet of Romantic music, still continues to be viewed in light of his mental breakdown, a sort of musical profile of his psychological state.

Now, exactly 200 years after Schumann’s birth, Martin Geck is coming to Schumann’s defense to shield him from such reductionist interpretative tendencies. On the occasion of this momentous bicentennial, the Düsseldorf musicologist has dedicated his efforts to presenting us with a biography that interpolates a chronological narration of the composer’s fortunes and misfortunes with highly readable accompanying essays focused on various individual pieces and specific moments of genesis within the composer’s life. Geck, too, has no doubts that Schumann’s music was shaped by his distinctive personality traits and that his life and work, in keeping with the universal aesthetic characteristic of the Romantic period, are “melded together in an almost symbiotic way,” as he emphasizes at the very beginning of the book – while still reminding us that this does not mean his work can be explained exhaustively by his life.

In response to the cliché of the raving musical genius, Geck paints the nuanced portrait of a highly reflective artist who, time and again, subordinates his overflowing creativity and pathological longsuffering in favor of an unrelenting work ethic and a musical approach marked by its clear and well-constructed poeticism. Schumann appears in this book as the heroic figure who faces and overcomes the yawning chasm of madness within his soul, an epic character who has attained his programmatic artistic aspiration of poetically reshaping subjective experience through the act of composition and thereby creating a new ethos with his music, one that reaches above and beyond the individual self – all the while showcasing a remarkable sense of discipline that extends to the very brink of his final breakdown.

Geck focuses on the phenomenon that is Schumann in all its complexity, illuminating the various concomitant facets with even-handed aplomb: Schumann as composer; as musical journalist, filled with literary ambitions; as politically active contemporary; as father of eight children, and as husband of highly celebrated piano virtuoso Clara Schumann.

When he turns to Robert’s relationship with the latter, the biographer zealously resumes his role as vindicator. According to a persistent rumor, he reports, Clara allegedly had a fling with the young Brahms as the end drew nigh for her solitary, clinic-bound husband. Geck brands this charge, however, as anchorless and sensationalistic. In formulating his formal objections to the allegation, Geck counters it not in his usual, even-handed manner but instead passionately, even polemically. And so, in these last pages of the book, the appreciation Geck has expressed throughout for Schumann the musician – as informed as it is accessible – gives way to a deep empathy for Schumann the person.

Schumann passed away on the afternoon of July 29, 1856. A man of a mere 46 years, he met his death in the Endenich Sanitorium. Two years prior to that – following a failed suicide attempt and suffering from severe auditory hallucinations – he had given his consent to be committed to this psychiatric institution in greater Bonn. “Melancholia with delusions” reads the diagnosis placed in his medical records at the time; after Schumann’s death, this annotation was also supplemented with the term “Paralysia.” The question as to whether these symptoms might be construed as long-term effects of syphilis, which Schumann is said to have acquired as a young man, is still the subject of debate today.

The diagnosis given the composer Schumann, born in Zwickau in 1810, has retained its mystifying inscrutability in spite of the wealth of source materials available to us; and this vague medical diagnosis became – in equally full measure – a disaster for the composer posthumously as ensuing generations projected it onto his music. Conductor Giuseppe Sinopoli, for example, has described Schumann’s second symphony in C major as “composed-out psychosis”; for composer Dieter Schnebel, the “Dichterliebe” lieder cycle, written in 1840 during Schumann’s first highly seminal creative period, conveys a “deeply rooted melancholic resignation, one crippling his will to live.”

Indeed, Schumann’s last orchestral work, the Violin Concerto in D minor, though kept from the public by the trustees of his estate until 1937, has won a permanent place in the repertoire of numerous violin virtuosos; yet this piece, as one of the late works by the great poet of Romantic music, still continues to be viewed in light of his mental breakdown, a sort of musical profile of his psychological state.

Now, exactly 200 years after Schumann’s birth, Martin Geck is coming to Schumann’s defense to shield him from such reductionist interpretative tendencies. On the occasion of this momentous bicentennial, the Düsseldorf musicologist has dedicated his efforts to presenting us with a biography that interpolates a chronological narration of the composer’s fortunes and misfortunes with highly readable accompanying essays focused on various individual pieces and specific moments of genesis within the composer’s life. Geck, too, has no doubts that Schumann’s music was shaped by his distinctive personality traits and that his life and work, in keeping with the universal aesthetic characteristic of the Romantic period, are “melded together in an almost symbiotic way,” as he emphasizes at the very beginning of the book – while still reminding us that this does not mean his work can be explained exhaustively by his life.

In response to the cliché of the raving musical genius, Geck paints the nuanced portrait of a highly reflective artist who, time and again, subordinates his overflowing creativity and pathological longsuffering in favor of an unrelenting work ethic and a musical approach marked by its clear and well-constructed poeticism. Schumann appears in this book as the heroic figure who faces and overcomes the yawning chasm of madness within his soul, an epic character who has attained his programmatic artistic aspiration of poetically reshaping subjective experience through the act of composition and thereby creating a new ethos with his music, one that reaches above and beyond the individual self – all the while showcasing a remarkable sense of discipline that extends to the very brink of his final breakdown.

Geck focuses on the phenomenon that is Schumann in all its complexity, illuminating the various concomitant facets with even-handed aplomb: Schumann as composer; as musical journalist, filled with literary ambitions; as politically active contemporary; as father of eight children, and as husband of highly celebrated piano virtuoso Clara Schumann.

When he turns to Robert’s relationship with the latter, the biographer zealously resumes his role as vindicator. According to a persistent rumor, he reports, Clara allegedly had a fling with the young Brahms as the end drew nigh for her solitary, clinic-bound husband. Geck brands this charge, however, as anchorless and sensationalistic. In formulating his formal objections to the allegation, Geck counters it not in his usual, even-handed manner but instead passionately, even polemically. And so, in these last pages of the book, the appreciation Geck has expressed throughout for Schumann the musician – as informed as it is accessible – gives way to a deep empathy for Schumann the person.

Translated by Gratia Stryker-Härtel

By Marianna Lieder

Marianna Lieder works as a freelance journalist and literary critic for publications including the Tagesspiegel, the Stuttgarter Zeitung and Literaturen. She has been an editor at Philosophie Magazin since 2011.