Lorenz PauliKathrin Schärer

Rigo und Rosa. 28 Geschichten aus dem Zoo und dem Leben

[Rigo and Rosa. 28 stories from inside and outside the zoo]

- Atlantis Verlag

- Zurich 2016

- ISBN 978-3-7152-0710-0

- 126 Pages

- 4 Suitable for age 5 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

Love makes you smart

The leopard wants to sleep. But he can’t, because there’s someone sobbing close by: a mouse! He wonders whether he should eat the mouse, or listen to what she has to say. But it’s already too late. The mouse explains that she’s afraid of wild animals, and asks him whether he can protect her. Anyone refusing a plea for help inevitably spends forever trying to justify it to themself. We are drawn irresistibly to help the weak, and in consequence even the leopard Rigo slips into the role of protector much more quickly than he might have thought possible. Though we also have to admit that Rigo is a pretty intelligent leopard, and has not been rendered bitter by his life within a zoo. The mouse interests him. He would particularly like to know what it feels like to be very small, yet at the same time enjoy complete freedom.

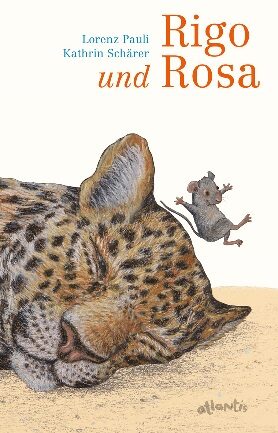

It’s not long before the mouse is taking all kinds of liberties with the leopard. We can already see this on the title page of Lorenz Pauli and Kathrin Schärer’s new book, "Rigo und Rosa". The mouse tames the old leopard, and sleeps cuddled up in his soft fur. When she’s awake, she asks him question after question: to ask a question is to call the shots, and so we find tiny little Rosa gaining the upper hand in the pair’s relationship. Rigo, the mighty but somewhat melancholic beast of prey, is perfectly happy with this state of affairs, for the go-getting little mouse awakens in him a joie de vivre that he had never even dreamt of.

It’s useful here to know that Lorenz Pauli originally devised his stories about the two animals for a column in the magazine "bärn!". The spur for this was the death in 2010 of a Persian leopard at Berne Zoo, featured extensively in the media. In Pauli’s series of narratives there is always a subtle undercurrent of sorrow, due not least to the fact that the dialogues between the two animals have a distinctly philosophical bent. The conversation always turns on such themes as love, beauty and death, and in developing them Pauli restricts himself solely to the scenery within the leopard’s enclosure. The structural implications of the 2-column format do make themselves felt, and repetitions are one result of this, but the brief narrative texts –– all written in a spirit of gentle wisdom – aren’t intended to be read straight through from beginning to end. Instead, we are invited to dip in and enjoy each one for itself as a kind of literary sweetmeat.

The language of the narratives is so pithy that they are instantly comprehensible, and lend themselves very well to being read aloud, and to serving as a basis for discussions with the children: what do they themselves think about friendship, about boredom, about story-telling? In these dialogues Lorenz Pauli stays firmly within the world of children, yet beneath the surface he also has much to say to adults.

For the book’s central theme is essentially love, which manifests itself here in myriad forms of closeness. Mouse fur and leopard fur happily co-exist; each of the creatures feels just so, but nobody is perfect. Rigo knows that leopards have smelly breath, but is Rosa shocked by this? ‘Your smelly breath is a part of you. On its own I’d find it horrible. But you and your smelly breath together ... that’s right and proper’, declares the mouse.

Kathrin Schärer, for whom this is already the tenth book in partnership with Lorenz Pauli, fully embraces the spirit of his concentrated, frill-free prose: avoiding minor details, she gives her illustrations their power to fascinate by focusing on the bodies of the two protagonists. She ensures that Rigo doesn’t come across as a cuddly pussy cat by giving him distinctly realistic features; he bares his teeth, and invites wary respect even when asleep, while the fun role is played by the mouse. With her virtuoso use of her hands and feet Rosa seems almost human. This all serves to win children’s hearts, and for all the stress on the contrast in both body and temperament we readily credit the pair’s happy sense of inner affinity.

It’s not long before the mouse is taking all kinds of liberties with the leopard. We can already see this on the title page of Lorenz Pauli and Kathrin Schärer’s new book, "Rigo und Rosa". The mouse tames the old leopard, and sleeps cuddled up in his soft fur. When she’s awake, she asks him question after question: to ask a question is to call the shots, and so we find tiny little Rosa gaining the upper hand in the pair’s relationship. Rigo, the mighty but somewhat melancholic beast of prey, is perfectly happy with this state of affairs, for the go-getting little mouse awakens in him a joie de vivre that he had never even dreamt of.

It’s useful here to know that Lorenz Pauli originally devised his stories about the two animals for a column in the magazine "bärn!". The spur for this was the death in 2010 of a Persian leopard at Berne Zoo, featured extensively in the media. In Pauli’s series of narratives there is always a subtle undercurrent of sorrow, due not least to the fact that the dialogues between the two animals have a distinctly philosophical bent. The conversation always turns on such themes as love, beauty and death, and in developing them Pauli restricts himself solely to the scenery within the leopard’s enclosure. The structural implications of the 2-column format do make themselves felt, and repetitions are one result of this, but the brief narrative texts –– all written in a spirit of gentle wisdom – aren’t intended to be read straight through from beginning to end. Instead, we are invited to dip in and enjoy each one for itself as a kind of literary sweetmeat.

The language of the narratives is so pithy that they are instantly comprehensible, and lend themselves very well to being read aloud, and to serving as a basis for discussions with the children: what do they themselves think about friendship, about boredom, about story-telling? In these dialogues Lorenz Pauli stays firmly within the world of children, yet beneath the surface he also has much to say to adults.

For the book’s central theme is essentially love, which manifests itself here in myriad forms of closeness. Mouse fur and leopard fur happily co-exist; each of the creatures feels just so, but nobody is perfect. Rigo knows that leopards have smelly breath, but is Rosa shocked by this? ‘Your smelly breath is a part of you. On its own I’d find it horrible. But you and your smelly breath together ... that’s right and proper’, declares the mouse.

Kathrin Schärer, for whom this is already the tenth book in partnership with Lorenz Pauli, fully embraces the spirit of his concentrated, frill-free prose: avoiding minor details, she gives her illustrations their power to fascinate by focusing on the bodies of the two protagonists. She ensures that Rigo doesn’t come across as a cuddly pussy cat by giving him distinctly realistic features; he bares his teeth, and invites wary respect even when asleep, while the fun role is played by the mouse. With her virtuoso use of her hands and feet Rosa seems almost human. This all serves to win children’s hearts, and for all the stress on the contrast in both body and temperament we readily credit the pair’s happy sense of inner affinity.

Translated by John Reddick

By Thomas Linden

Thomas Linden is a journalist (Kölnische Rundschau, WWW.CHOICES.DE) specializing in the areas of literature, theater and film. He also curates exhibitions on photography and picture book illustration.