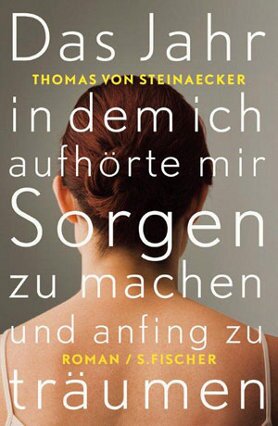

Thomas von Steinaecker

Das Jahr, in dem ich aufhörte, mir Sorgen zu machen, und anfing zu träumen

[The year in which I stopped worrying and began to dream]

- S. Fischer Verlag

- Frankfurt am Main 2012

- ISBN 978-3-10-070408-5

- 389 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Thomas von Steinaecker

Das Jahr, in dem ich aufhörte, mir Sorgen zu machen, und anfing zu träumen

[The year in which I stopped worrying and began to dream]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Russian (2012 - 2014).

Sample translations

Review

The demand for writers to engage with the things that drive our contemporary lives, and most of all our day-to-day work, is currently being brought to their attention with some vehemence. These things include crisis and self-exploitation, opaque power structures, the obsession with optimisation, and the pressure to represent oneself.

All this is contained in Thomas Steinaecker’s novel, whose wonderful title sets up the book’s ambivalence: The year in which I stopped worrying and began to dream. On the one hand, this sounds like a fluffy self-help guide, in the style of How to stop worrying and start living. On the other, if you can ignore the feel-good management speak and delve into its actual meaning, there is something liberating, transitory, and therefore literary about it. And von Steinaecker fulfils both his aims admirably: the realistic depiction of the world of work, and an explicitly artistic route to this depiction.

Sitting on the bus or the tube in the morning, who hasn’t wondered about those women in their early forties, in their good suits and uncomfortable shoes, with blister plasters on their heels and an unreadable expression on their faces - what do they really do all day, where do they disappear to for ten or twelve hours? This novel tells us.

Renate Meißner is 42 years old, and has just been transferred from Frankfurt am Main to Munich by the large insurance firm she works for. Promoted, and compulsorily transferred. For years, she had been having an affair with her married boss in Frankfurt, and after Renate tried to force him to make a decision about their relationship, he abruptly got rid of her. The year is 2008, and the financial crisis is gathering pace. Renate, a risk protection specialist, watches as the certainties of her own existence disappear into thin air one by one.

Renate, as we gradually discover, is on the fast track to a nervous breakdown. The gulfs in her life grow ever greater, the holes begin to gape. The evaluations she performs on herself are a desperate attempt to stay in control; she undergoes a progressive emotional atrophy; the intervals between her doses of psychiatric medication gradually decrease. She lurches through her days from opaque client meetings to opaque private evening engagements; from fits of despair on the parquet floor of her new Munich flat, to the indistinct structures within her branch of the insurance company. Then crisis hits: Renate is selected to report on her own department’s efficiency. This is not a good way to turn colleagues into friends.

Von Steinaecker’s language as he narrates Renate’s disastrous spiritual decline is efficient, and so cool it almost reaches freezing point. His protagonist, it seems at first, is not capable of anything more. But this is no self-help book – nor is it the autobiographical account of somebody 'opting out', and von Steinaecker, as we have seen in his previous books, is an author who is master of not one but many realities, with the ability to interlink them all.

In the second part of the novel, which is interspersed with fuzzy black and white photos (less illustrative than irritating, they mainly serve to distort reality), von Steinaecker sends his heroine into an alternative world which is downright surreal. Renate travels to Russia, to meet the owner of an amusement-park empire who wants to enter into an agreement with the insurance firm. In this 97-year-old woman, Renate thinks she recognises her own grandmother, who had disappeared decades previously, supposedly after being involved in a car accident.

Here in Russia, it becomes apparent how sublime the fantastical worlds von Steinaecker creates (or puts together from set pieces) can be, as they reflect back to us the reflexes and fears of our reality. This woman, who is nothing but a façade, is plunged back into something genuine. But there's little she can do with this – and how could she? Von Steinaecker has taken the idyll of opting out, escaping into a pleasurable but healthy existence, and revealed it as a no less disturbing situation than the sedated life Renate led before: here is a woman who has had the career ladder sawn off above and below her, and is now forced to be alone with herself in an empty space. A nightmarish idea.

All this is contained in Thomas Steinaecker’s novel, whose wonderful title sets up the book’s ambivalence: The year in which I stopped worrying and began to dream. On the one hand, this sounds like a fluffy self-help guide, in the style of How to stop worrying and start living. On the other, if you can ignore the feel-good management speak and delve into its actual meaning, there is something liberating, transitory, and therefore literary about it. And von Steinaecker fulfils both his aims admirably: the realistic depiction of the world of work, and an explicitly artistic route to this depiction.

Sitting on the bus or the tube in the morning, who hasn’t wondered about those women in their early forties, in their good suits and uncomfortable shoes, with blister plasters on their heels and an unreadable expression on their faces - what do they really do all day, where do they disappear to for ten or twelve hours? This novel tells us.

Renate Meißner is 42 years old, and has just been transferred from Frankfurt am Main to Munich by the large insurance firm she works for. Promoted, and compulsorily transferred. For years, she had been having an affair with her married boss in Frankfurt, and after Renate tried to force him to make a decision about their relationship, he abruptly got rid of her. The year is 2008, and the financial crisis is gathering pace. Renate, a risk protection specialist, watches as the certainties of her own existence disappear into thin air one by one.

Renate, as we gradually discover, is on the fast track to a nervous breakdown. The gulfs in her life grow ever greater, the holes begin to gape. The evaluations she performs on herself are a desperate attempt to stay in control; she undergoes a progressive emotional atrophy; the intervals between her doses of psychiatric medication gradually decrease. She lurches through her days from opaque client meetings to opaque private evening engagements; from fits of despair on the parquet floor of her new Munich flat, to the indistinct structures within her branch of the insurance company. Then crisis hits: Renate is selected to report on her own department’s efficiency. This is not a good way to turn colleagues into friends.

Von Steinaecker’s language as he narrates Renate’s disastrous spiritual decline is efficient, and so cool it almost reaches freezing point. His protagonist, it seems at first, is not capable of anything more. But this is no self-help book – nor is it the autobiographical account of somebody 'opting out', and von Steinaecker, as we have seen in his previous books, is an author who is master of not one but many realities, with the ability to interlink them all.

In the second part of the novel, which is interspersed with fuzzy black and white photos (less illustrative than irritating, they mainly serve to distort reality), von Steinaecker sends his heroine into an alternative world which is downright surreal. Renate travels to Russia, to meet the owner of an amusement-park empire who wants to enter into an agreement with the insurance firm. In this 97-year-old woman, Renate thinks she recognises her own grandmother, who had disappeared decades previously, supposedly after being involved in a car accident.

Here in Russia, it becomes apparent how sublime the fantastical worlds von Steinaecker creates (or puts together from set pieces) can be, as they reflect back to us the reflexes and fears of our reality. This woman, who is nothing but a façade, is plunged back into something genuine. But there's little she can do with this – and how could she? Von Steinaecker has taken the idyll of opting out, escaping into a pleasurable but healthy existence, and revealed it as a no less disturbing situation than the sedated life Renate led before: here is a woman who has had the career ladder sawn off above and below her, and is now forced to be alone with herself in an empty space. A nightmarish idea.

Translated by Ruth Martin

By Christoph Schröder

Christoph Schröder, born 1973, lives and works as a freelance author and reviewer in Frankfurt am Main. Among others, he writes for ZEIT, Deutschlandfunk and SWR Culture.