Felicitas HoppeMichael Sowa

Iwein Löwenritter

[Iwein, the knight of the lion]

- S. Fischer Verlag

- 2008

- ISBN 978-3-596-85259-8

- 256 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Felicitas Hoppe

Iwein Löwenritter

[Iwein, the knight of the lion]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Spanish: Argentina (2009 - 2011).

Sample translations

Review

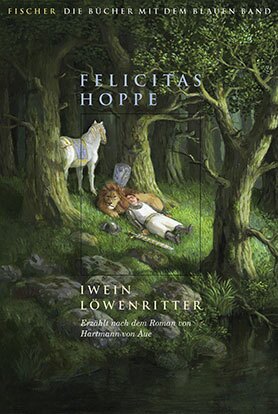

In her first book for children the writer Felicitas Hoppe, who has won many awards and distinctions for her work, tells the story of Iwein, the Knight of the Lion. It is based on the Middle High German verse novel written around the year 1200 by Hartmann von Aue, a version of an Arthurian legend which in turn took its inspiration from a romance by the French poet Chrétien de Troyes. Felicitas Hoppe thus has a wealth of traditional material to draw on for her children’s book. The result is a captivating and sensitively told story, rich in images, which carries the reader away into a fairy-tale world.

Iwein, the Knight of the Lion is divided into two large sections. The first part, “Iwein”, describes Iwein’s departure from the court of King Arthur and his marriage to Laudine. Then we hear how the knight loses all his good fortune and has to start from the beginning again. The second part, “The Knight of the Lion”, tells readers how Iwein successfully survives further adventures with the lion beside him – and in the end finds his way back to Laudine. This division into two reflects the double structure of the medieval original. (It should be mentioned that Felicitas Hoppe has a thorough grounding in the Middle High German Iwein.) The two-part structure also makes it easier to survey the complex plot, something to be borne in mind when writing for young readers. In addition, the further division of the story into very short chapters helps readers to find their way. These chapters are only three to five pages long, and have descriptive titles indicating their themes.

Felicitas Hoppe follows Hartmann von Aue in her account of large parts of the course of the action, but she realizes that she must, in a way, “translate” the story for young readers. What exactly does it mean when Iwein and Laudine exchange their hearts? And why does Iwein leave his wife again, although he has only just married her and loves her more than his life? To solve the problem of such potential questions, Felicitas Hoppe has created an omnipresent narrator. Where the plot is not immediately easy for readers who have not studied the literature of the Middle Ages to understand, he explains it to them. The voice of this narrator addresses children directly at the beginning of the book, as if he were reading aloud and taking them into his confidence.

“Do you know the story of Iwein, who set out one day, feeling bored, in search of adventures, exchanged his heart for another’s and so lost his wits? After that he wandered through the Everwood and had to fight a thousand monsters, but everything ended well after all. Would you like to know how that happened? Then listen to me carefully, because no one can tell you the story better – I was there myself.”

In Hoppe’s version, Iwein is an adventurer who is tired of hearing nothing but made-up stories at the court of King Arthur. “Adventure” (Hoppe’s free translation of Middle High German âventiure) tempts him so much that he sets out without saying goodbye to King Arthur or his own best friend Gawain. In the “Land Nearby”, a monstrous man wearing animal skins and covered with dirt tells him the way to the source of storms. Once there, Iwein does not hesitate to pour water on the rock as he has been told to do. A terrible storm immediately breaks out, but the storyteller makes it clear that this is no ordinary storm, for as he points out to the reader, in this distant land full of adventures even a storm has a monstrous dimension. “You know what storms are like yourselves. First comes lightning, then thunder, and then rain. But this storm was worse than thunder and lightning, and the rain that followed was not rain but hail, and the hailstones struck down everything that lives and breathes.”

Iwein himself falls to the ground, but he has to get to his feet at once, for the lord of that land, a terrifying knight, appears and challenges the intruder to single combat. Iwein fights well, wounds his opponent severely, and puts him to flight. He pursues the knight to his castle, but his enemy manages to get to safety, leaving Iwein caught between the two gates at the entrance to the castle. His situation seems hopeless, but then the clever Lunete appears. She shows Iwein a way of escape and gives him a ring to make him invisible. Thus armed, Iwein enters the fortress and sees the lord of the castle die of his wounds. When he sets eyes on Laudine, the knight’s wife and now his widow, he falls in love with her at once.

Lunete cleverly pulls the strings to make sure that her mistress is willing to accept a new husband – Laudine now falls in love with Iwein. The couple marry, and as the original medieval poem puts it, exchange hearts. Not a very simple process, as the narrator suggests: “I can tell you that it wasn’t easy. You have to go about it very carefully, because the heart is very sensitive. After all, Iwein’s heart was used to Iwein’s chest, and Laudine’s heart was used to hers.” From then on, Iwein and Laudine are bound to each other for ever.

But at this moment Sir Gawain, Iwein’s best friend from King Arthur’s court, arrives. He rouses Iwein’s old wish for adventure again. Iwein asks his newly married wife for leave of absence (MHG urloup, a word surviving into modern German as Urlaub = leave, vacation, holiday), and promises to be back in a year’s time to the day. Laudine is sad but allows her husband to go. In the year that follows Iwein tests his knightly prowess at tournaments with Gawain, and does more than justice to his reputation as the “best of the best” among knights. But in the frenzied excitement of victory he forgets the passing of time, and misses the end of the year – a bad mistake. Now it is not so easy for him to return to Laudine. He goes out of his mind with grief.

The narrator explains what that means: “If you ask me what the worst thing for human beings is, I will tell you: not pain, not fear, not guilt. Nor even despair. The worst thing is loneliness. Because loneliness goes to the human heart and from there spreads to everywhere else. Loneliness makes everything confused and bewildering, and even extinguishes memory.” Such passages are among the great strengths of the book, bringing the characters vividly to life.

Of course Iwein recovers. He saves a lion’s life and finds the great beast a faithful companion. Together, they go through a number of adventures until Iwein is himself again. Once more he is “the best of the best”. And then it is time for him to ask Laudine to forgive him, for he still has her heart in his breast, and she has his in hers …

Hoppe’s Iwein, the Knight of the Lion reads like a brilliantly told fairy-tale in which images of a legendary world full of adventures rise of their own accord. There are places where the reader may even see associations with the mysterious forest where Matt’s Fort stands in Astrid Lindgren’s Ronia the Robber’s Daughter, or the wild-rose valley of The Brothers Lionheart. Four wonderful illustrations by Michael Sowa help the reader’s own powers of imagination. But the book sweeps readers irresistibly along not least because of the narrator of Hoppe’s story, who takes children by the hand and leads them straight into her fantasy world: “So forget school, and imagine a forest instead.” We may wonder whether his style of narrative is really meant first and foremost for the young people to whom the publisher recommends the story, but without a shadow of doubt this is an outstanding book for children to read – or to be read to them – and indeed for everyone who loves cleverly and imaginatively told stories.

Iwein, the Knight of the Lion is divided into two large sections. The first part, “Iwein”, describes Iwein’s departure from the court of King Arthur and his marriage to Laudine. Then we hear how the knight loses all his good fortune and has to start from the beginning again. The second part, “The Knight of the Lion”, tells readers how Iwein successfully survives further adventures with the lion beside him – and in the end finds his way back to Laudine. This division into two reflects the double structure of the medieval original. (It should be mentioned that Felicitas Hoppe has a thorough grounding in the Middle High German Iwein.) The two-part structure also makes it easier to survey the complex plot, something to be borne in mind when writing for young readers. In addition, the further division of the story into very short chapters helps readers to find their way. These chapters are only three to five pages long, and have descriptive titles indicating their themes.

Felicitas Hoppe follows Hartmann von Aue in her account of large parts of the course of the action, but she realizes that she must, in a way, “translate” the story for young readers. What exactly does it mean when Iwein and Laudine exchange their hearts? And why does Iwein leave his wife again, although he has only just married her and loves her more than his life? To solve the problem of such potential questions, Felicitas Hoppe has created an omnipresent narrator. Where the plot is not immediately easy for readers who have not studied the literature of the Middle Ages to understand, he explains it to them. The voice of this narrator addresses children directly at the beginning of the book, as if he were reading aloud and taking them into his confidence.

“Do you know the story of Iwein, who set out one day, feeling bored, in search of adventures, exchanged his heart for another’s and so lost his wits? After that he wandered through the Everwood and had to fight a thousand monsters, but everything ended well after all. Would you like to know how that happened? Then listen to me carefully, because no one can tell you the story better – I was there myself.”

In Hoppe’s version, Iwein is an adventurer who is tired of hearing nothing but made-up stories at the court of King Arthur. “Adventure” (Hoppe’s free translation of Middle High German âventiure) tempts him so much that he sets out without saying goodbye to King Arthur or his own best friend Gawain. In the “Land Nearby”, a monstrous man wearing animal skins and covered with dirt tells him the way to the source of storms. Once there, Iwein does not hesitate to pour water on the rock as he has been told to do. A terrible storm immediately breaks out, but the storyteller makes it clear that this is no ordinary storm, for as he points out to the reader, in this distant land full of adventures even a storm has a monstrous dimension. “You know what storms are like yourselves. First comes lightning, then thunder, and then rain. But this storm was worse than thunder and lightning, and the rain that followed was not rain but hail, and the hailstones struck down everything that lives and breathes.”

Iwein himself falls to the ground, but he has to get to his feet at once, for the lord of that land, a terrifying knight, appears and challenges the intruder to single combat. Iwein fights well, wounds his opponent severely, and puts him to flight. He pursues the knight to his castle, but his enemy manages to get to safety, leaving Iwein caught between the two gates at the entrance to the castle. His situation seems hopeless, but then the clever Lunete appears. She shows Iwein a way of escape and gives him a ring to make him invisible. Thus armed, Iwein enters the fortress and sees the lord of the castle die of his wounds. When he sets eyes on Laudine, the knight’s wife and now his widow, he falls in love with her at once.

Lunete cleverly pulls the strings to make sure that her mistress is willing to accept a new husband – Laudine now falls in love with Iwein. The couple marry, and as the original medieval poem puts it, exchange hearts. Not a very simple process, as the narrator suggests: “I can tell you that it wasn’t easy. You have to go about it very carefully, because the heart is very sensitive. After all, Iwein’s heart was used to Iwein’s chest, and Laudine’s heart was used to hers.” From then on, Iwein and Laudine are bound to each other for ever.

But at this moment Sir Gawain, Iwein’s best friend from King Arthur’s court, arrives. He rouses Iwein’s old wish for adventure again. Iwein asks his newly married wife for leave of absence (MHG urloup, a word surviving into modern German as Urlaub = leave, vacation, holiday), and promises to be back in a year’s time to the day. Laudine is sad but allows her husband to go. In the year that follows Iwein tests his knightly prowess at tournaments with Gawain, and does more than justice to his reputation as the “best of the best” among knights. But in the frenzied excitement of victory he forgets the passing of time, and misses the end of the year – a bad mistake. Now it is not so easy for him to return to Laudine. He goes out of his mind with grief.

The narrator explains what that means: “If you ask me what the worst thing for human beings is, I will tell you: not pain, not fear, not guilt. Nor even despair. The worst thing is loneliness. Because loneliness goes to the human heart and from there spreads to everywhere else. Loneliness makes everything confused and bewildering, and even extinguishes memory.” Such passages are among the great strengths of the book, bringing the characters vividly to life.

Of course Iwein recovers. He saves a lion’s life and finds the great beast a faithful companion. Together, they go through a number of adventures until Iwein is himself again. Once more he is “the best of the best”. And then it is time for him to ask Laudine to forgive him, for he still has her heart in his breast, and she has his in hers …

Hoppe’s Iwein, the Knight of the Lion reads like a brilliantly told fairy-tale in which images of a legendary world full of adventures rise of their own accord. There are places where the reader may even see associations with the mysterious forest where Matt’s Fort stands in Astrid Lindgren’s Ronia the Robber’s Daughter, or the wild-rose valley of The Brothers Lionheart. Four wonderful illustrations by Michael Sowa help the reader’s own powers of imagination. But the book sweeps readers irresistibly along not least because of the narrator of Hoppe’s story, who takes children by the hand and leads them straight into her fantasy world: “So forget school, and imagine a forest instead.” We may wonder whether his style of narrative is really meant first and foremost for the young people to whom the publisher recommends the story, but without a shadow of doubt this is an outstanding book for children to read – or to be read to them – and indeed for everyone who loves cleverly and imaginatively told stories.

Translated by Anthea Bell

By Eva Kaufmann