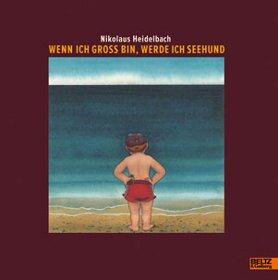

Nikolaus Heidelbach

Wenn ich groß bin, werde ich Seehund

[When I grow up I'm going to be a seal]

- Beltz & Gelberg Verlag

- Weinheim/ Basel 2011

- ISBN 978-3-407-79443-7

- 32 Pages

- 3 Suitable for age 4 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Nikolaus Heidelbach

Wenn ich groß bin, werde ich Seehund

[When I grow up I'm going to be a seal]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Russian (2012 - 2014).

Sample translations

Review

Nikolaus Heidelbach is a bold writer. He has sufficient faith in his abilities to tackle really big, serious topics. But he also has faith in children, believing them capable not only of being interested in such weighty issues, but also of being emotionally and intellectually up to dealing with them in all their gravity. In this undertaking the Cologne author and illustrator knows exactly what he is doing; after all, he has had more than thirty years’ experience at it - experience that almost from the very beginning has found recognition in numerous awards and prizes. His refusal to shy away from heavyweight topics is evident even in early examples of his very considerable output such as “Kleiner dicker Totentanz” (1984) and “Kleines Alphabet für Tierquäler und Kinderfreunde” (1986).

It would be a signal mistake, however, to expect o find oneself confronted by a depressing and overly challenging read. Heidelbach, who not only wrote the text of “Wenn ich groß bin, werde ich ein Seehund” (‘When grow up I’m going to be a seal’) but also produced the drawings, presents a story that is clear and straightforward, yet richly illustrated. He shows himself to be a master of watercolour illustrations: the resolutely flat images focus on only a small number of elements, their clarity enhanced by the broad, blank margin that surrounds them. In some instances the figures escape from their frame and achieve maximum impact by standing out starkly from their white background.

The narrative seems to mimic the calm equilibrium of the sea. The natural colours, muted yet never pallid, reinforce this sense - but while the interiors seem timeless, the more one looks and the more one reads and re-reads, the more it becomes clear that this story is not set in some timeless past but in the present day. It is indeed no coincidence that Heidelbach prefaces the book with a quotation from David Thomson’s Song of the Seal: it transpires that, like Thomson, Heidelbach really does take us into the world of Irish and Scottish legend.

‘I never had to learn to swim: I could do it from the very beginning’: so runs the first sentence - and there the boy is, swimming like a fish, and dancing around with the fish above and below the surface of the water. Against the backdrop of the fairytale floor of the sea - already familiar to the reader from the front endpaper - Heidelbach sketches the harmonious outlines of an intense pattern of life. Enormous vistas of sea, sky and sand, all stretching as far as the eye can see. The boy’s father, a fisherman, is intimately involved with the sea; his mother looks after the house - each week one room gets an especially thorough clean - and doesn’t dare to dip even so much as a toe in the water. The boy’s career intentions, already announced in the title of the book, seem all of a piece with the neat and orderly family façade, they seem to represent a clearcut if touchingly naive aspiration.

But just as the story plunges into the shadowy world below the surface even before the start of the actual narrative, so too the mother’s tales open up a different realm, for her sea is peopled by fabulous creatures with evocative names, and the boy’s dreams are filled with a seemingly never-ending procession of mermaids, princely squid, deathly jellyfish and sea trolls. This fantastic and opulent panorama occupies no fewer than seven pages, and Heidelbach uses it to change the whole mood of the book: from this point onwards it is the world below the surface that determines the rhythm and atmosphere of the rest of the story, whilst retrospectively also showing the preceding pages in a far more ambiguous light than we might have supposed. The book’s title, too, acquires new meaning, for it now bears witness to the reaction of the boy to a fateful event.

We would not wish to give away the book’s decisive plot-twist, so let us simply say that Nikolaus Heidelbach contrives by means of simple yet powerful language to deal with serious issues encountered by children, and to do so in a way that genuinely reflects their own perspective. He does this out of a firm conviction that no topic is excessively demanding for children provided that it is presented appropriately and with due seriousness, and that instead of adult-world language they are offered scope for their own imaginative interpretation of things, and, above all, telling images of those matters that concern them.

Heidelbach’s success in conveying all of this rests partly on his crystal-clear language, but also on his wonderful watercolours, which simultaneously conjure up polar opposites: orderliness and exuberant fantasy; the depiction of stolid quotidian reality and its shift into the rich plenitude of dreams. These opposites serve to enhance one another, each illuminates new facets of the other, and in so doing they create an intensely truthful book that is a feast for both mind and eye.

It would be a signal mistake, however, to expect o find oneself confronted by a depressing and overly challenging read. Heidelbach, who not only wrote the text of “Wenn ich groß bin, werde ich ein Seehund” (‘When grow up I’m going to be a seal’) but also produced the drawings, presents a story that is clear and straightforward, yet richly illustrated. He shows himself to be a master of watercolour illustrations: the resolutely flat images focus on only a small number of elements, their clarity enhanced by the broad, blank margin that surrounds them. In some instances the figures escape from their frame and achieve maximum impact by standing out starkly from their white background.

The narrative seems to mimic the calm equilibrium of the sea. The natural colours, muted yet never pallid, reinforce this sense - but while the interiors seem timeless, the more one looks and the more one reads and re-reads, the more it becomes clear that this story is not set in some timeless past but in the present day. It is indeed no coincidence that Heidelbach prefaces the book with a quotation from David Thomson’s Song of the Seal: it transpires that, like Thomson, Heidelbach really does take us into the world of Irish and Scottish legend.

‘I never had to learn to swim: I could do it from the very beginning’: so runs the first sentence - and there the boy is, swimming like a fish, and dancing around with the fish above and below the surface of the water. Against the backdrop of the fairytale floor of the sea - already familiar to the reader from the front endpaper - Heidelbach sketches the harmonious outlines of an intense pattern of life. Enormous vistas of sea, sky and sand, all stretching as far as the eye can see. The boy’s father, a fisherman, is intimately involved with the sea; his mother looks after the house - each week one room gets an especially thorough clean - and doesn’t dare to dip even so much as a toe in the water. The boy’s career intentions, already announced in the title of the book, seem all of a piece with the neat and orderly family façade, they seem to represent a clearcut if touchingly naive aspiration.

But just as the story plunges into the shadowy world below the surface even before the start of the actual narrative, so too the mother’s tales open up a different realm, for her sea is peopled by fabulous creatures with evocative names, and the boy’s dreams are filled with a seemingly never-ending procession of mermaids, princely squid, deathly jellyfish and sea trolls. This fantastic and opulent panorama occupies no fewer than seven pages, and Heidelbach uses it to change the whole mood of the book: from this point onwards it is the world below the surface that determines the rhythm and atmosphere of the rest of the story, whilst retrospectively also showing the preceding pages in a far more ambiguous light than we might have supposed. The book’s title, too, acquires new meaning, for it now bears witness to the reaction of the boy to a fateful event.

We would not wish to give away the book’s decisive plot-twist, so let us simply say that Nikolaus Heidelbach contrives by means of simple yet powerful language to deal with serious issues encountered by children, and to do so in a way that genuinely reflects their own perspective. He does this out of a firm conviction that no topic is excessively demanding for children provided that it is presented appropriately and with due seriousness, and that instead of adult-world language they are offered scope for their own imaginative interpretation of things, and, above all, telling images of those matters that concern them.

Heidelbach’s success in conveying all of this rests partly on his crystal-clear language, but also on his wonderful watercolours, which simultaneously conjure up polar opposites: orderliness and exuberant fantasy; the depiction of stolid quotidian reality and its shift into the rich plenitude of dreams. These opposites serve to enhance one another, each illuminates new facets of the other, and in so doing they create an intensely truthful book that is a feast for both mind and eye.

Translated by John Reddick

By Michael Sellhoff

Michael Sellhoff is a research associate at the Philosophical Seminar of the University of Kiel and is a freelance editor.