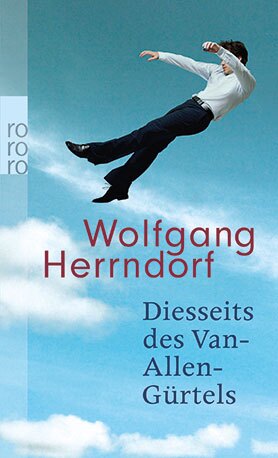

Wolfgang Herrndorf

Diesseits des Van-Allen-Gürtels

[This Side of the Van Allen Belt]

- Rowohlt Buchverlag

- Reinbek 2007

- ISBN 978-3-8218-5794-7

- 188 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Wolfgang Herrndorf

Diesseits des Van-Allen-Gürtels

[This Side of the Van Allen Belt]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Portuguese: Brazil (2007 - 2008).

Sample translations

Review

Everyone knows everyone, it’s said, with six degrees of separation. In Wolfgang Herrndorf’s new story collection This Side of the Van Allen Belt there are even fewer degrees. The protagonists of his stories are acquaintances, friends or even relatives. Most of them appear several times over in stories that are linked in time frame or plot; someone who has a secondary role in one story becomes the main character in the next, and vice versa. The sense of a larger connectedness emerges, but does not obscure the fact that these are individual stories that stand alone and can be read that way. Each of the six pieces centers on something very special to be discovered.

The Soldier’s Path tells of a strange love triangle and of an art student who promptly breaks off his studies to work as a car painter. In the Oderbruch a canoeist whose car has been stolen plays table tennis with a young girl in a remote house in the forest while waiting (in vain) for the police to come. In Wonderful, This View the employees of an ad agency engage in fun more forced than voluntary at a party thrown by their boss, who seems to have lost the knack of separating friendship and career. In The Flower of Tsingtao a nurse breaks off all connections to home, sets off on a trip around the world and ends up imprisoned in Japan for multiple homicide.

We encounter Herrndorf’s characters in very different situations and scenarios. Similarly, the protagonists’ milieus, educational levels and professions (if they have one) are anything but homogeneous. Nonetheless, the characters all have more – and more significant – things in common with one another than their age (between thirty and forty). What connects them is their attitude toward life, their view of the world. At one point they are spoken of as “inwardly uninvolved”, they live without really taking part in what happens around them. There is no lack of feeling and empathy. This is how it sounds: “Mara had the usual clichéd disorders like slit forearms, and she always ground out her cigarettes on her knuckles when no one was looking. But otherwise she was perfectly all right.”

No one is happy here, but with no perspectives, even an escape from accustomed surroundings offers no prospect of change: “I [...] tried to picture my future. All I managed was a feeling of total emptiness.” Lacking all ties and orientation, the characters move, often helplessly, in what for them is a “strangely incomprehensible universe”.

In the title story This Side of the Van Allen Gürtel, which won Wolfgang Herrndorf the audience award at the Klagenfurt Literary Competition, the narrator becomes aware of his own lack of visions. Instead of going to his girlfriend’s party, he gets drunk with a teenage boy on the balcony of the apartment next door. As the boy rhapsodizes about his future – he wants to become an astronaut and fly to the moon – the narrator realizes that he never had such ambitious goals: “I always wanted to be a white-collar worker”. With a certain touch of sadism he proceeds to destroy the boy’s dreams by telling him the moon landing was just staged in a Hollywood studio.

It is hard to work up much sympathy for Herrndorf’s heroes. What is worse, it is impossible to shake the uncomfortable feeling that what Herrndorf describes is not far at all from the reality of his generation. He himself has no intention of offering such diagnoses of the times. As one of the stories puts it: “It is important to me to state that I cast no moral judgment here. I am the last person to chime in with the old fogies’ chorus of cultural pessimism [...].”

Herrndorf aims to situate his stories as close as possible to reality. His style is deliberately artless, his dialogues drawn from everyday life – so demonstratively that the reader grows suspicious when this claim to authenticity appears in the last story, entitled Zentrale Intelligenz Agentur (ZIA). Here Herrndorf describes the founding meeting of an association which actually exists, coming to broad public awareness when Kathrin Passig won the Bachmann Prize. Herrndorf himself belongs to the association as an “unofficial collaborator”. Against the backdrop of a rundown chateau in Brandenburg he conjures up well-known “notorious troublemakers” and “Berlin-Mitte people” from the cultural scene: in exaggerated caricature we meet Joachim Lottmann, Wiglaf Droste and of course Holm Friebe, the founder of the ZIA. Those familiar with the scene will doubtless be able to identify other guests as well. Various wonder women from the Leipzig Literature Institute have been invited “as window dressing”. The whole thing ends in excesses of alcohol and drugs that leave the ZIA’s actual purpose in the dark to the very last. What reads superficially as a one-to-one reproduction of reality reveals itself to be a trenchant satire of the contemporary Berlin cultural machine.

Though some of the stories’ themes may be depressing, the book as a whole is not. On the contrary. Like one of his heroes, Herrndorf studied painting at the academy in Nuremberg, and he is a highly precise observer, producing exact portraits of people and situations with just a few words. These descriptions have something scathingly revealing and are often extremely funny. The wonderfully laconic language and a plot that keeps drifting unexpectedly into the grotesque and absurd keeps the reader laughing out loud. As when the female narrator in the last story runs into “four skinheads and a moped” on a village square at night, sings them songs by Störkraft and Frank Rennicke – because all they know is Eminem – and is rewarded with a beer.

What remains in the end? Herrndorf has no message to convey: “My only ambition is to provide you with great entertainment [...]” he has one of his protagonists announce. And in that, one can say whole-heartedly, the author is a complete success!

The Soldier’s Path tells of a strange love triangle and of an art student who promptly breaks off his studies to work as a car painter. In the Oderbruch a canoeist whose car has been stolen plays table tennis with a young girl in a remote house in the forest while waiting (in vain) for the police to come. In Wonderful, This View the employees of an ad agency engage in fun more forced than voluntary at a party thrown by their boss, who seems to have lost the knack of separating friendship and career. In The Flower of Tsingtao a nurse breaks off all connections to home, sets off on a trip around the world and ends up imprisoned in Japan for multiple homicide.

We encounter Herrndorf’s characters in very different situations and scenarios. Similarly, the protagonists’ milieus, educational levels and professions (if they have one) are anything but homogeneous. Nonetheless, the characters all have more – and more significant – things in common with one another than their age (between thirty and forty). What connects them is their attitude toward life, their view of the world. At one point they are spoken of as “inwardly uninvolved”, they live without really taking part in what happens around them. There is no lack of feeling and empathy. This is how it sounds: “Mara had the usual clichéd disorders like slit forearms, and she always ground out her cigarettes on her knuckles when no one was looking. But otherwise she was perfectly all right.”

No one is happy here, but with no perspectives, even an escape from accustomed surroundings offers no prospect of change: “I [...] tried to picture my future. All I managed was a feeling of total emptiness.” Lacking all ties and orientation, the characters move, often helplessly, in what for them is a “strangely incomprehensible universe”.

In the title story This Side of the Van Allen Gürtel, which won Wolfgang Herrndorf the audience award at the Klagenfurt Literary Competition, the narrator becomes aware of his own lack of visions. Instead of going to his girlfriend’s party, he gets drunk with a teenage boy on the balcony of the apartment next door. As the boy rhapsodizes about his future – he wants to become an astronaut and fly to the moon – the narrator realizes that he never had such ambitious goals: “I always wanted to be a white-collar worker”. With a certain touch of sadism he proceeds to destroy the boy’s dreams by telling him the moon landing was just staged in a Hollywood studio.

It is hard to work up much sympathy for Herrndorf’s heroes. What is worse, it is impossible to shake the uncomfortable feeling that what Herrndorf describes is not far at all from the reality of his generation. He himself has no intention of offering such diagnoses of the times. As one of the stories puts it: “It is important to me to state that I cast no moral judgment here. I am the last person to chime in with the old fogies’ chorus of cultural pessimism [...].”

Herrndorf aims to situate his stories as close as possible to reality. His style is deliberately artless, his dialogues drawn from everyday life – so demonstratively that the reader grows suspicious when this claim to authenticity appears in the last story, entitled Zentrale Intelligenz Agentur (ZIA). Here Herrndorf describes the founding meeting of an association which actually exists, coming to broad public awareness when Kathrin Passig won the Bachmann Prize. Herrndorf himself belongs to the association as an “unofficial collaborator”. Against the backdrop of a rundown chateau in Brandenburg he conjures up well-known “notorious troublemakers” and “Berlin-Mitte people” from the cultural scene: in exaggerated caricature we meet Joachim Lottmann, Wiglaf Droste and of course Holm Friebe, the founder of the ZIA. Those familiar with the scene will doubtless be able to identify other guests as well. Various wonder women from the Leipzig Literature Institute have been invited “as window dressing”. The whole thing ends in excesses of alcohol and drugs that leave the ZIA’s actual purpose in the dark to the very last. What reads superficially as a one-to-one reproduction of reality reveals itself to be a trenchant satire of the contemporary Berlin cultural machine.

Though some of the stories’ themes may be depressing, the book as a whole is not. On the contrary. Like one of his heroes, Herrndorf studied painting at the academy in Nuremberg, and he is a highly precise observer, producing exact portraits of people and situations with just a few words. These descriptions have something scathingly revealing and are often extremely funny. The wonderfully laconic language and a plot that keeps drifting unexpectedly into the grotesque and absurd keeps the reader laughing out loud. As when the female narrator in the last story runs into “four skinheads and a moped” on a village square at night, sings them songs by Störkraft and Frank Rennicke – because all they know is Eminem – and is rewarded with a beer.

What remains in the end? Herrndorf has no message to convey: “My only ambition is to provide you with great entertainment [...]” he has one of his protagonists announce. And in that, one can say whole-heartedly, the author is a complete success!

Translated by Isabel Fargo Cole

By Anne Nordmann