BOOKWORLD

Germans Search for their Identity while Democracy Fears for its Future

The book season is starting somewhat nervously this spring. As was the case in previous years, this is related to the major problem areas – democratic fatigue, right-wing populism and fear of digitalization – that make the twenty-first century very much a work in progress. Non-fiction writers are playing their part in exploring the massive shifts in moral and ethical consensus ongoing in the Federal Republic of Germany. A number of books focus on democracy and worry about its robustness. Whether thy talk about Brexit, Trump’s America, Orban’s Hungary or the growing acceptance of an openly racist political party in Germany, social scientists, historians and philosophers are alarmed. Leading the way is Till van Rahden, whose Demokratie. Eine gefährdete Lebensform (Democracy, An Endangered Species – Campus) tells the story of Germany’s arduous road to democracy after 1945.

Several books published in late 2019 and early 2020 tackle the current situation. In Abschied vom Abstieg. Eine Agenda für Deutschland (Departure from Decline: An Agenda for Germany - Rowohlt Berlin), Herfried and Marina Münkler discuss how irrational German fears of impoverishment provide an opening for populists into the mainstream. In his Grenzen der Demokratie. Teilhabe als Verteilungsproblem (Limits of Democracy: Participation as a Problem of Inequality - Reclam), Stephan Lessenich offers an impassioned plea for a radical expansion of national rights to include people with the status of refugees. In her polemic Was ist die Nation? (What is the Nation? - Steidl), Ulrike Guérot tries to win over all those who have trouble divorcing themselves from the nation-state to the idea of a “united states of Europe.” And in her brand-new Sprache und Sein (Language and Being – Hansa Berlin), Kübra Gümüsay argues for a politically sensitized use of everyday language, especially when referring to people of non-German heritage who were born or have lived for a long time in Germany. The exclusionary power of language, she argues, is increasingly used to draw lines between majority society and people defined in terms of minorities such as “the Muslims.” Naika Foroutan’s Die postmigrantische Gesellschaft. Ein Versprechen der pluralen Demokratie (The Post-Migrant Society: A Promise of Pluralistic Democracy - Transcript) pursues a similar direction, while with Warum Demokratien Helden brauchen (Why Democracies Need Heroes - Ullstein), the St. Gallen philosopher Dieter Thomä gives us an intellectual history of heroism for our post-heroic age. The inspiration for this book was Emmanuel Macrons question: “Why should there not be such a thing as democratic heroism?”

Another topic contemporary German non-fiction authors are taking up is the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Last year there was a veritable flood of histories, analyses and arguments that, against the backdrop of the refugee “crisis” and the populist xenophobia of the PEGIDA movement, investigated what twenty-first-century German identity could mean. Now that the excitement about the anniversary of the fall of the wall itself has dissipated, several carefully written, multi-media-oriented books are taking a look at the year when East Germany joined the Federal Republic. Foremost is Jan Wenzel’s sensational collage Das Jahr 1990 freilegen (Uncovering the Year 1990 - Spector Books), which collects and arranges original articles, speeches, advertisements and magazine photos, yielding an archaeological portrait of the year of German reunification. In Patrick Bauer’s Der Traum ist aus. Aber wir werden alles geben (The Dream is Over But We Will Give Our All - Rowohlt Berlin) investigates the prehistory of 1990 in the form of a narrative history of the crucial anti-communist demonstration on November 4, 1989. Last summer, Uta Heyder published Born in the GDR. Angekommen in Deutschland. 30 Lebensberichte nach Tonbandprotokollen aus Sachsen, Sachsen-Anhalt und Thüringen (Born in the GDR, Ended Up in Germany: 30 Life Stories Based on Recordings from Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia - Bussert & Stadeler). And Siegbert Schefke recalls his time as a film-material dissident. His Als die Angst die Seite wechselte. Die Macht der verbotenen Bilder (When Fear Changed Sides: The Power of Banned Images - Transit) is about two young men who influenced the course of world history by illegally filming the Monday demonstrations in Leipzig.

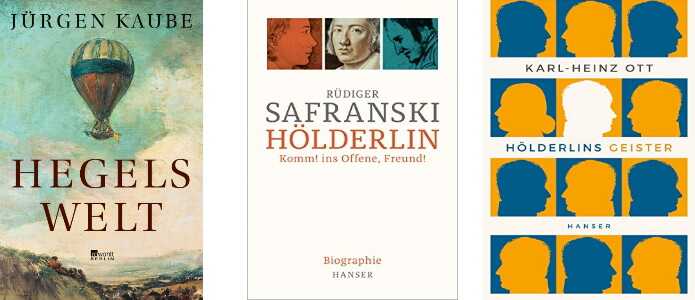

Last but not least, German non-fiction is very much on home ground as it celebrates two important anniversaries of German idealism amidst what contemporaries regarded as the extremely bewildering situation of the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. Klaus Vieweg serves up the first comprehensive biography of Hegel, Hegel. Der Philosoph der Freiheit (Hegel: Philosopher of Freedom - C.H. Beck), while another, Jürgen Kaube’s Hegels Welt (Hegel’s World – Rowohlt Berlin), is scheduled for the summer. Carl Jung biographer Sebastian Ostritsch also pays tribute to the great systematic thinker in Hegel. Der Weltphilosoph (Hegel, The World Philosopher - Propyläen). The birthday of Hegel’s friend Hölderlin is marked in books by Rüdiger Safranski, Komm, ins Offene! Freund (Come into the Open, Friend - Hanser), and Karl-Heinz Ott, Hölderlins Geister (Hölderlin’s Spirits - Hanser). Poets and thinkers experienced tempestuous days in the revolutionary Europe of those days, and in Napoleon, Hegel even saw the world spirit itself riding in on horseback. Far from just dutifully marking anniversaries, today’s German non-fiction shows how a look at the past can help us contextualize our own era and face its dangers with our critical faculties.

Katharina Teutsch is a journalist and critic who works for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Die Zeit, PhilosophieMagazin and Deutschlandradio Kultur, among other outlets. She is also a member of the jury for the Leipzig Book Prize.

Translated by Jefferson Chase