Bookworld

The Re-politicisation of the Novel

Contemporary German-speaking literature is smug and apolitical. That, at any rate, was its reputation a few years back. However, quite the reverse is true now. Since Autumn 2020, the world of the novel has also become an arena for socio-critical debate. Who counts in our society, and whose voices are we hearing? Racism, sexism and class-consciousness are no longer mere phrases in our identity-conscious society: they are a lived reality. How can novels play their part in conveying this?

Last Autumn, Covid-related workplace closures and the cancellation of the Frankfurt Book Fair meant that numerous publication dates had to be pushed back. However, the trend towards politicised literature has remained the same. Retail book sales slumped by around 30% during the first three months of this year, as compared with the pre-Covid year 2019. This striking decline was acknowledged by the German Publishers and Booksellers Association; their president, Karin Schmidt-Friederich even went so far as to refer to this as a “catastrophic figure”. However, novels with an autobiographical slant - written from a female perspective, by those who feel marginalised on account of their skin colour, race and gender - are bucking the trend.

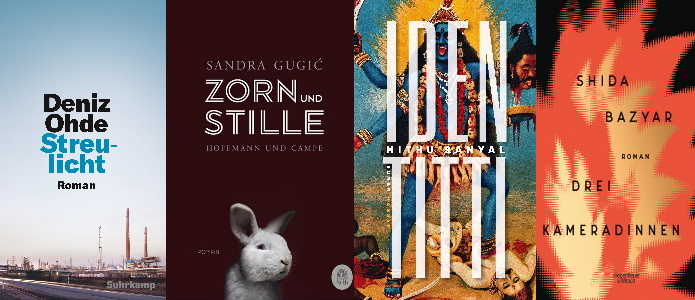

Deniz Ohde’s anonymous protagonist, for example, is the daughter of a Turkish woman and a working-class German man. In Streulicht (Sky Glow), she recounts her obstacle-strewn ascent from the grimy streets of industrial Frankfurt to the heights of university. As someone who grew up in the 90s, the protagonist of this highly praised debut novel remembers a time in which people thought the on-stage characters of Dragan and Alder were funny, whilst asylum seekers’ homes were being burned down.

The Austrian author Sandra Gugić likewise demonstrates in her novel Zorn und Stille (Anger and Silence) the ways in which deeply rooted prejudice can divide a family. Asra and Sima Banadinović arrive in Vienna from Yugoslavia towards the end of the 1970s. As migrant workers they uncomplainingly work their fingers to the bone. Their oldest daughter, who grows up in Austria, can’t begin to understand her parents’ way of life, and ultimately severs her relationship with them - while they cling doggedly to their national pride and their belief that Slobodan Milošević is to be the saviour of Yugoslavia.

We find an equally nuanced and humorous examination of so-called identity politics in Mithu Sanyal’s issue-based campus novel Identitti. Student Nivedita is the daughter of a Polish woman and an Indian man. Her world falls apart when Professor Sarasawati - whom Nivedita has idolised as a woman of colour and general life guru - is unmasked and stands revealed as a white German. Nivedita had been led by Saraswati’s theories to believe that she had finally been understood. Now, though, it isn’t just Saraswati who is unmasked, but an entire paradox at the heart of the way people view identity politics. Although inequality based on skin colour, ethnic origin or gender will eventually be overcome, the emotionally charged characteristics of ‘identity’ are still all too clearly evident in our contemporary society.

The same is true in Shida Bazyar’s novel Drei Kameradinnen (Sisters in Arms). In this, Bazyar demonstrates the differing perspectives of the dominant white population and people of colour either with or without a German passport. Saya, Hani and Kasih grow up together in a run-down block of flats at the edge of a small German town, and progress to their respective studies and apprenticeships. Following this, they all return home for a wedding. Their happy reunion, however, is overshadowed by the beginnings of the NSU Trial. This gives the three young women all the more reason to unite in solidarity with one another and to feel all the more angry with the Nazis. Cleverly, Bazyar’s narrator also provokes her readers, suggesting that they, too, may be prone to prevaricate and to jump to hasty conclusions.

That said: the issue at the heart of this novel is clear - as it is with all the others mentioned above. They are all attempts to awaken empathy. As we know, literature lends itself particularly well to this. Discrimination can’t be conveyed just via facts and figures. These authors and their characters give us a far better insight than mere statistics into the wishes, longings, hopes and fears of those who walk this path. These characters may be fictional, but they can still add their voices to contemporary socio-political debate.

Miriam Zeh works as a freelance literary critic and literary scholar in Frankfurt and Mainz, and presents radio shows for stations including Deutschlandfunk. She is also co-editor of POP Kultur & Kritik magazine, and is involved with the Books up! initiative (www.booksup.me / https://www.instagram.com/booksup.me/)

Translated by Helena Kirkby

Deniz Ohde’s anonymous protagonist, for example, is the daughter of a Turkish woman and a working-class German man. In Streulicht (Sky Glow), she recounts her obstacle-strewn ascent from the grimy streets of industrial Frankfurt to the heights of university. As someone who grew up in the 90s, the protagonist of this highly praised debut novel remembers a time in which people thought the on-stage characters of Dragan and Alder were funny, whilst asylum seekers’ homes were being burned down.

The Austrian author Sandra Gugić likewise demonstrates in her novel Zorn und Stille (Anger and Silence) the ways in which deeply rooted prejudice can divide a family. Asra and Sima Banadinović arrive in Vienna from Yugoslavia towards the end of the 1970s. As migrant workers they uncomplainingly work their fingers to the bone. Their oldest daughter, who grows up in Austria, can’t begin to understand her parents’ way of life, and ultimately severs her relationship with them - while they cling doggedly to their national pride and their belief that Slobodan Milošević is to be the saviour of Yugoslavia.

We find an equally nuanced and humorous examination of so-called identity politics in Mithu Sanyal’s issue-based campus novel Identitti. Student Nivedita is the daughter of a Polish woman and an Indian man. Her world falls apart when Professor Sarasawati - whom Nivedita has idolised as a woman of colour and general life guru - is unmasked and stands revealed as a white German. Nivedita had been led by Saraswati’s theories to believe that she had finally been understood. Now, though, it isn’t just Saraswati who is unmasked, but an entire paradox at the heart of the way people view identity politics. Although inequality based on skin colour, ethnic origin or gender will eventually be overcome, the emotionally charged characteristics of ‘identity’ are still all too clearly evident in our contemporary society.

The same is true in Shida Bazyar’s novel Drei Kameradinnen (Sisters in Arms). In this, Bazyar demonstrates the differing perspectives of the dominant white population and people of colour either with or without a German passport. Saya, Hani and Kasih grow up together in a run-down block of flats at the edge of a small German town, and progress to their respective studies and apprenticeships. Following this, they all return home for a wedding. Their happy reunion, however, is overshadowed by the beginnings of the NSU Trial. This gives the three young women all the more reason to unite in solidarity with one another and to feel all the more angry with the Nazis. Cleverly, Bazyar’s narrator also provokes her readers, suggesting that they, too, may be prone to prevaricate and to jump to hasty conclusions.

That said: the issue at the heart of this novel is clear - as it is with all the others mentioned above. They are all attempts to awaken empathy. As we know, literature lends itself particularly well to this. Discrimination can’t be conveyed just via facts and figures. These authors and their characters give us a far better insight than mere statistics into the wishes, longings, hopes and fears of those who walk this path. These characters may be fictional, but they can still add their voices to contemporary socio-political debate.

Miriam Zeh works as a freelance literary critic and literary scholar in Frankfurt and Mainz, and presents radio shows for stations including Deutschlandfunk. She is also co-editor of POP Kultur & Kritik magazine, and is involved with the Books up! initiative (www.booksup.me / https://www.instagram.com/booksup.me/)

Translated by Helena Kirkby