The Literary World

Norm-critical, autofictional, historical

The pandemic has thrown us onto our own devices. Whereas in 2020 the keynote was still solidarity as we sought to cope with the prevailing uncertainties together with others, albeit only virtually, in 2021 we found ourselves more or less on our own. One indicator of this was the increased use of social media, which according to online surveys undertaken by the major broadcasters recorded a significant increase in traffic.

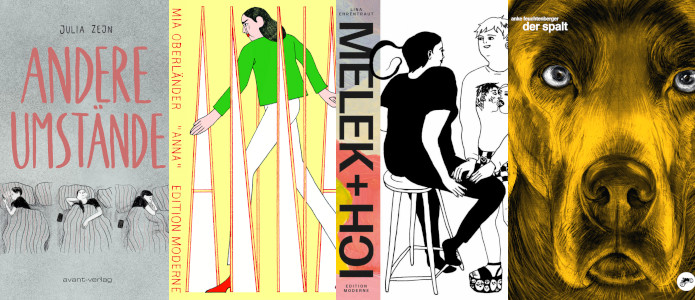

Julia Zejn’s Andere Umstände (‘Pregnant...’; Avant Verlag) offers a marvellous example. In this, her second graphic novel, Julia Zejn tells the story of Anna, who becomes pregnant accidentally and opts for an abortion even though objectively speaking there is no reason why she shouldn’t go ahead and have a child: she is almost thirty, she is in a steady relationship, and she has a job; furthermore, she can readily envisage starting a family at some point in the future. Zejn demonstrates that the decision to have an abortion is essentially a purely personal one – and that whilst most pregnant women who contemplate abortion certainly think about it very deeply, the decision doesn’t always have to be the traumatic one that general opinion often supposes it to be.

In Mia Oberländer’s Anna (Edition Moderne) the female body plays an especially big role - in the literal sense of the word. Oberländer’s debut work is the story of three women, all related to each other, and all larger than is deemed ‘normal’. Particularly in the rural environment where they live, their size makes them the butt of unwanted attention. Anna is a story about what it’s like for people who don’t fit in, and, more specifically, don’t match the prevailing ideals of body shape peddled on social media.

Melek + ich (‘Melek + me’; Edition Moderne), Leipzig illustrator Lina Ehrentraut’s first novel, is also about bodies, but in a broader sense. In a mixture part science fiction, part arthouse, Ehrentraut narrates an expressionistically illustrated gay love story, with more or less explicit depictions of the female body – including nipples and pubic hair. With these and other such details she is drawing our attention to something that is rarely seen on social media – not least because the various internet platforms simply wipe all depictions of it – namely the (female) human body in its natural state.

In Anke Feuchtenberger’s Der Spalt (‘Cracks’; Reprodukt) the female body – or part of it at least – also plays a major role. Here, a little girl asks what a ‘crack’ is, and her question is the cue for a poetic illustrated story in which the first-person narrator tries to explain the word’s meanings by drawing on a whole succession of different examples.

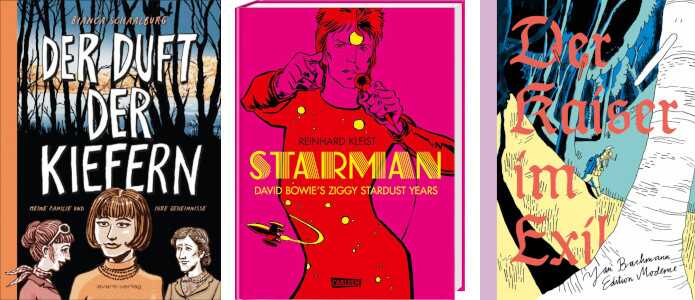

Attempts to resolve self-identity issues through one’s art can also often mean writers taking a look at their family history – as is the case in Der Duft der Kiefern (‘The scent of the pines’; Avant Verlag). In this graphic novel the Berlin illustrator and author Bianca Schaalburg confronts the Nazi past of her grandfather, and explores her childhood in a divided city.

Where looking into the future seems impossible or simply too disturbing, people tend to turn to stories from the past. That, at any rate, appears to explain the trend amongst some comic-book authors in 2021 to place historical figures at the centre of their work. Thus for instance the 75th anniversary of David Bowie’s birth saw the publication recently of the graphic novel Starman (Carlsen Verlag), in which Reinhard Kleist retraces the Ziggy Stardust years of the pop musician, who died in 2016.

The protagonist has been dead for somewhat longer in Jan Bachmann’s most recent comic book, Der Kaiser in seinem Exil (‘The Kaiser in his exile’; Edition Moderne), which depicts Wilhelm II in exile in Holland and offers a wonderfully absurd caricature of the superannuated Kaiser. Its relevance to the situation today is horrifyingly clear when one considers the Hohenzollerns’ current restitution claims.

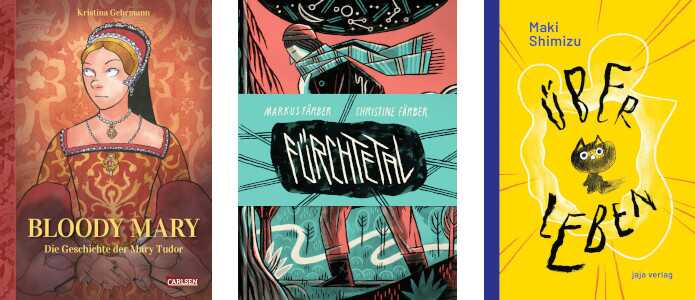

We’re also in royal territory in Bloody Mary (Carlsen Verlag), in which the Hamburg author Kristina Gehrmann traces the life story of Queen Mary I, the first female monarch of England. As well as detailing the brutal measures that were implemented by Mary in her determination to re-establish catholicism in 16th century England, and which led to her being nicknamed ‘Bloody Mary’, Gehrmann also spotlights the fears that beset this noblewoman from the House of Tudor throughout her entire life.

Also worth noting here is the comic book Über Leben (‘About life’; JaJa Verlag), in which Maki Shimizu, a Berliner by choice rather than by birth, offers a sequence of illustrations amounting in effect to a social study, combined with a narrative structured like a detective story. As well as focusing on topics such as death, violence and abuse, she highlights big-city gentrification and homelessness – but also friendship and solidarity.

There is clearly a trend discernible in the books published in 2021 that could well continue in 2022 and provide us with all sorts of exciting autofictional material. Comic book artists may well continue to put a premium on working through issues to do with their identity and their own life story – and perhaps stories about individuals will then meld together once again to yield a more powerful sense of the broader social context.

Sophia Zessnik works for the Berlin newspaper Taz as a journalist and as an editor/contributor in the social media section. She writes chiefly about literature by younger writers, toxic maleness, and social issues more generally - especially when these things are presented in the form of comics. In addition, she deals with mental health matters in her column ‘Great Depression’.

Translation by John Reddick

Copyright: © Litrix.de