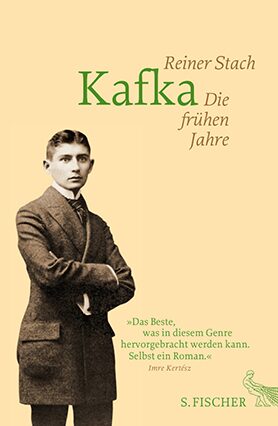

Reiner Stach

Kafka. Die frühen Jahre

[Kafka. The early days]

- S. Fischer Verlag

- Frankfurt am Main 2014

- ISBN 978-3100751300

- 608 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Reiner Stach

Kafka. Die frühen Jahre

[Kafka. The early days]

Sample translations

A novel without fiction: The 3rd volume of Reiner Stach’s biographical trilogy tells the story of Kafka's literary beginnings

In the case of the previous volumes, reactions had been skeptical to Stach’s ambitious project of writing a novelistic biography aspiring to the status of an independent literary work. Now, however, many have enthusiastically confirmed that Stach has truly fulfilled this objective. In turn, Stach--originally a mathematician and literary scholar-- may take credit for having created with his trilogy something like a new genre: a novel without fiction which for all its stupendous wealth of material does not contain anything invented.

The early years of Kafka, whom Stach with some justification designates an “author for the millennium,” was the most difficult part of the biographer’s innovative project. For this phase of the writer’s life is scarcely documented in any direct form. The reason Stach built the foundation of his Kafka edifice only after constructing the first and second floors was chiefly because he had long hoped to be able to use Max Brod’s diaries for narrating the period between 1883 and 1911. Yet those writings still remain inaccessible due to the ongoing--and thoroughly Kafkaesque— dispute over Brod’s estate.

However, readers are richly compensated for this disappointment, thanks to Stach’s painstaking research on the social, intellectual, and (everyday) cultural history of the late Habsburg Empire, not to speak of the world beyond it. A multicolored panorama of the period emerges from sections on the history of Prague and of Kafka’s family, as well as those on the political tensions and cultural currents that shaped the writer’s childhood, adolescence, education, and early career. In Stach’s scenic and often anecdotal narrative, this panorama achieves an enormous density and vibrancy.

Stach’s discrete empathy has been repeatedly praised, for he follows the traces of Kafka’s life without drawing interpretive conclusions about the fictional oeuvre. However, in this new book addressing the birth, development, and emancipation of an extraordinary talent, the biographer does not abstain completely from literary analysis. Nonetheless, a quasi-organic component of Stach’s account, as in the previous volumes, includes his speculations about Kafka's inner life and the elegant way he switched into (what he termed as) his "mode of perception.” This may at times be irritating, but it is enlightening for readers of Kafka whenever it pairs empathy with research. For instance, Stach’s personal feeling for Kafka's sense of humor brings to light vital evidence brilliantly documenting an important aspect of the writer’s life that most interpreters have overlooked.

Another feature of this (beautifully illustrated) Kafka biography demonstrates its outstanding merit. Although written on the basis of impressive erudition, it is not only intended for an academic audience of specialists but rather for all those interested in the writer/person Franz Kafka and his times--or for those who, motivated by this portrayal of his life, will be for the first time discover their interest in him. Accordingly, the 600 pages of this (finally) published opening volume are not only intimidating but also inviting; and even Stach’s annotations are capable of captivating readers, something entirely unique in the realm of literary studies.

Translated by David A. Brenner

By Kristina Maidt-Zinke

Kristina Maidt-Zinke is a book and music critic at the Süddeutsche Zeitung and also writes reviews for Die Zeit.

Publisher's Summary

THE CONCLUSION OF THE MAJOR KAFKA BIOGRAPHY

"The best of this genre. A novel in and of itself." Imre Kertész

After receiving rave reviews for his brilliant first three volumes of Kafka’s biography, Reiner Stach concludes his major work with Kafka's childhood, adolescence, university studies and early career. The book focuses on key aspects of Kafka’s life, such as the evolution of his unique voice, educational experiences, his sexual coming of age and, last but not least, his exploration of new technologies and media. Reiner Stach’s Kafka biography is internationally renowned as a standard work that explores literary biography in an entirely new way. Once again, Reiner Stach has fashioned a dense narrative and a colorful panoramic view of the era, while creating an empathetic portrait of an extraordinary man.

The Complete Works:

Kafka. The Early Years (1883 - 1910)

Kafka. The Decisive Years (1910 - 1915)

Kafka. The Years of Insight (1916 - 1924)

(Text: S. Fischer Verlag)