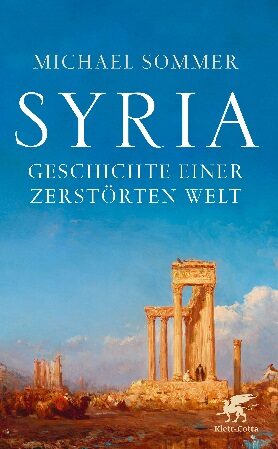

Michael Sommer

Syria. Geschichte einer zerstörten Welt

[Syria: History of a Destroyed World]

- Klett-Cotta Verlag

- Stuttgart 2016

- ISBN 978-3-608-94977-3

- 217 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

Before the truth wars: Michael Sommer examines the history of a destroyed world

In his short monograph, Syria: History of a Destroyed World, historian of antiquity Michael Sommer presents a model study that fruitfully takes up Assmann’s considerations, in this case focusing on the history of the cultural space between the Mediterranean and the Tigris in early and late antiquity. Sommer‘s book is particularly controversial in two respects. It examines the historical roots of the cultural space which the Romans called Syria and which today is brutally enmeshed in proxy and guerrilla wars, in what many observers describe as a kind of "World War III." At the same time, it is a provocative analysis of social paradigms and religious systems in early and late antiquity, inasmuch as it maps out a highly lucid, virtually neo-humanistic image of the different imperial cultures and their mentalities.

For, in both ancient and Hellenistic pantheons, the principle of "translatability" was operative in matters of religious systems and mythologies. The myths of antiquity (including the Jewish ones) were a collective "writing project" (Sommer), which was being worked on from the Indus to Britain and which was intended to benefit all imperial societies. In this newly integrated region of the globe, structural membership usually resulted from Roman citizenship. It did not exclude religious conflicts, for instance. But these were quite different in nature from those conflicts that would arise from the "absolute" claim to truth of fundamentalist monotheism (a relatively late development in the history of faith in an all-encompassing non-dualistic God). Such conflicts continue into the present.

The central concepts governing cultural harmony in these empires were pantheon and paideia. At concrete and symbolic places of memory in the region of Syria--such as Issos, Palmyra, Jerusalem, or Hatra--Sommer shows succintly and imaginatively how such vastly expanded cultural spaces could be shaped in relative peace (and consciously in accordance with political theology and culture). These were spaces produced by people who understood themselves, at one and the same time, as culturally-Greek Roman citizens as well as Jews or "pagan" Syrians. In this sense, the Issos chapter on Alexander’s empire serves as a model within what is already a model work of history.

There Sommer provides a fresh, fascinating, and revealing perspective on the "war-horse" of history (Franz Kafka), without which the phenomenon of Hellenism would scarcely have existed. By way of example: education (paideia) in Greek mythology, literature, philosophy, and the art of living had become a matter of course for most Jews in the Jerusalem of Jesus’s time. Paideia was the classical program of education which encompassed all spheres of life, whether religious, spiritual, or philosophical. Amid the multiple and splintered Jewish groups, such as the Zealots, Pharisees, or Sadducees, an intensification of political theology began to emerge such that it could only be "pacified" by Rabbinic Judaism after the Romans had destroyed the (Second) Temple.

In a manner both sober and highly stimulating, Michael Sommer succeeds masterfully in highlighting the past so that every distinct detail illuminates a complex context. In the process, he opens up a number of vistas for questioning stereotypes: among them, the alleged separation of the Orient and Occident, the notion of Hellenistic decadence, and claims that "pagans" were typically primitive and violent. On the other hand, one cannot really separate the "horizontal" and "vertical" anchoring of a member of Hellenistic culture (identity is the wrong term for characterizing such plurality) in a multicultural space of memory and history--one in which history and myth have been thought through to their conclusion. Which is, after all, the point of the theory of cultural memory.

Translated by David A. Brenner

By Marius Meller

Marius Meller studied German philology, philosophy, and musicology, and has worked as a literary editor at the Frankfurter Rundschau and Berliner Tagesspiegel newspapers. He lives in Berlin as a writer and works as a freelance literature critic for Deutschlandradio and Deutschlandfunk.

Publisher's Summary

With its iconoclasm, the IS has destroyed irreplaceable cultural treasures. Michael Sommer sets a bridge between the present and classical antiquity: he masterfully tells and interprets the eventful history of a unique cultural landscape, which continues to be a constituent part of our identity.

(Text: Klett-Cotta Verlag)