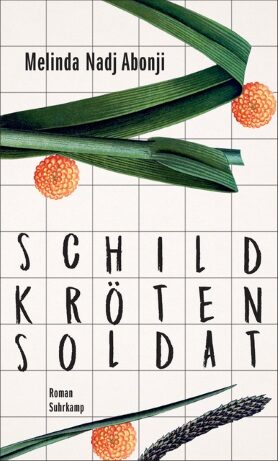

Melinda Nadj Abonji

Schildkrötensoldat

[Tortoise Soldier]

- Suhrkamp Verlag

- Berlin 2017

- ISBN 978-3-518-42759-0

- 173 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Melinda Nadj Abonji

Schildkrötensoldat

[Tortoise Soldier]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Arabic II (2015 - 2018).

Sample translations

The poetry of gentle resistance

This novel, too, takes place in Melinda Nadj Abonji’s birthplace, the multi-ethnic province of Vojvodina, and takes the reader back to 1991, the year the Yugoslav wars began. Zoltán Kertész, nickname Zoli, the son of a half-gypsy father and day-labourer mother, grew up in rural poverty, and although he is regarded by others as mentally retarded, he is in fact an exceptionally sensitive outsider and highly imaginative dreamer who is completely out of place not only in the rough-edged community of his village but also in his dismal family home, wrecked as it is by drink and a pervasive sense of hopelessness.

What Zoli most likes doing is spending his time in the garden, talking to the trees and flowers and to his dog Tango. He bestows a certain order on the incomprehensible world around him by making up crosswords, and breaking words down into their constituent elements. By dint of a sort of gentle friendship he enjoys a warm bond with his cousin Hanna, who has emigrated to Switzerland, and who is clearly the author’s alter ego. Following Zoli’s premature death she travels to Serbia to investigate the background to this sad turn of events. Her narrative voice is deployed to parallel and mimic that of the protagonist, who - fully aware of his disability and his otherness - speaks about his life in an idiosyncratically poetic language that verges on the surreal.

The baker he worked for having beaten him half to death, Zoli shows symptoms of epilepsy, and appears no longer fit for any kind of work. His parents, as ignorant as they are feckless, want to make a ‘real man’ out of him and force him to join the army. There, he tries to save himself by behaving like a tortoise, doing everything slowly and retreating into his shell at every opportunity. But a gentle eccentric and ingenuous innocent such as Zoli can’t help but be destroyed by the brutality of the military machine with its dirty tricks and its humiliations. When the relentless drills bring about the death of his only friend, Jenö, he goes completely to pieces and is discharged from the army as ‘incurably insane’, and dies soon afterwards from an epileptic seizure.

Melinda Abonji shows the hidden side and inner make-up of the violence that wreaks such destruction at the front line of the war. But she also shows that the engine that drives all wars - the dull but oppressive routine of power and subjugation, of orders and obedience - can be subverted by the wilful use of inventive language combined with a rebellious imagination. The rebel with the mind of a child may meet a tragic end, but the author - a musician as well as a writer - endows him with his own special voice and his own special language (a considerable challenge for translators!), and in so doing flies a flag for the world’s misfits and dissenters. At the same time, too, this moving story is a stirring monument to a broken land, and a homeland now lost.

Translated by John Reddick

By Kristina Maidt-Zinke

Kristina Maidt-Zinke is a book and music critic at the Süddeutsche Zeitung and also writes reviews for Die Zeit.

Publisher's Summary

Zoltán Kertész, blue-eyed son of a »half gypsy« and a day labourer with constantly changing lovers, is the outsider of his little town in Serbia. When a child, he fell out of his father’s hands and off the back of a speeding motorcycle and later, unable to carry a sack of flour through a bakery quickly enough, the baker he was working for beat him bloody. Ever since he has suffered »a fluttering of the temples«, and is happiest sitting in his barn doing crossword puzzles. When the Yugoslavian civil war breaks out in 1991, his parents see it as his big chance: in the People’s Army the »good-for-nothing« and »idiot« will become a man and then a hero. But Zoltán doesn’t fit in, he asks the wrong questions and, on top of it all, stutters when he does. After his only friend’s collapse on a pointless training march turns out to be fatal, Zoltán refuses to play the game anymore with a system that has given all the power to the strongest.

Through pulsating, musical language and vivid images that evoke the power of the wild and winglike nature of thought, in Tortoise Soldier Melinda Nadj Abonji tells the story of the soft resistance imagination establishes against the restrictions of a system which recognises only commands, obedience, and submission.

(Text: Suhrkamp Verlag)