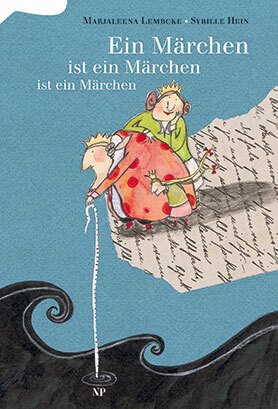

Marjaleena LembckeSybille Hein

Ein Märchen ist ein Märchen ist ein Märchen

[A fairy tale is a fairy tale is a fairy tale]

- Nilpferd im G&G Verlag

- St. Pölten - Wien - Linz 2004

- ISBN 3-85326-285-6

- 124 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Marjaleena Lembcke

Ein Märchen ist ein Märchen ist ein Märchen

[A fairy tale is a fairy tale is a fairy tale]

Sample translations

Review

What’s a King to do when everything in his castle suddenly stops working? First of all he’s surprised – but, finding that being surprised doesn’t help, he sets out into the great wide world to find out why everything has been disturbed.

Thus begins Marjaleena Lembke’s modern fairy tale, which has searching as its central theme: there’s the writer who’s searching for ideas, and the fairy tale figures who are searching for their author. Interwoven with this are questions about the relationship between the fictive world and reality. It’s a fairy tale that on the one hand sticks to the rules of the fairy tale genre – but at the same time, it works on the Russian doll principle, in that it opens up a whole series of different narrative levels before managing to tie them all together at the end.

The story begins, as we know, in the royal fairy tale palace: the family are having breakfast and, as usual, are waiting to be served their coffee by their countless servants. But all of a sudden the servants stop moving. The writer has clearly stopped writing, so the figures don’t know what they are supposed to do next. The castle starts to feel chilly, so the family decide to go and try to sort things out for themselves.

The family undertake this journey of discovery in the real world outside the fairy tale: in the modern world with its shopping centres and workers’ demonstrations. However, it quickly transpires that the ‘real’ people are only aware of the fairy tale figures – and the other invented figures – when they encounter them in books. What a frustrating experience for a royal family!

The book alternates between the main story and short interludes of a parallel plot concerning the dilemma of the writer whose inspiration has failed him. He wanders around despondently, and meets an old tramp in the park, whose simple logic and wisdom reveal the true purpose of fairy tales to the writer: fairy tales exist so that we can dream – and such dreams make us a little happier. And, moreover, you must finish what you started!

But let’s return to our royal family. In the town are all sorts of characters wandering around homeless because they were only allowed to appear fleetingly in their stories before being crossed out. Page Thirteen is one such boy; he wasn’t even given a name as he was so unimportant. But the Princess finds him quite charming! The fate of the poor children moves the King and his family, and so they decide to take the homeless children with them; they intend to to return to the castle with the help of the somewhat inscrutable Count von Mnemonic and to dictate their own lives from now onwards. But, naïve as fairy tale characters tend to be, they fall into the Count’s trap: he’s a fairy tale children-catcher and, moreover, one who spends his whole time typing stories into his computer only to delete them all again. But fortunately Page Thirteen is a cunning street child, and he manages to free them all again with the help of the writer. Together they move in to the castle, and the writer finally manages to write a story which has a place for everyone.

With her fairy tale, Marjaleena Lembcke has created a multi-layered and original collage of well known fairy tales and stories. In them, a delight in using quotations is ideally accompanied by something perfectly suited to children: a capacity to turn something familiar into something unfamiliar. By doing this, she has written a quite new fairy tale (as the tramp says: “There’s bound to be some fairy tale out there somewhere that doesn’t exist yet”) with an open ending. Ultimately, what we find is a fairy tale within a fairy tale, in which the figures are constantly discussing the subject of fairy tales, along with the relationship between “poetry” and “truth”. And, of course, Lembcke’s figures relate to the traditional canon of fairy tale values just as much as did those in her story’s predecessors. Thus the fate of the “Little Mermaid” is invoked for upbringing purposes just as much as the wicked stepmother from “Snow White”.

As befits the genre, the fairy tale figures are entirely representative of types rather than being individuals. However, their individual dealings with language constitute the particular comedy of Lembcke’s fairy tale. Whilst the King carries on using his peculiar kingly expressions, the vocabulary of his wife and daughter changes very quickly, and they adapt to their changed situation linguistically. Particularly amusing is the episode when the street children are assigned the task of telling fairy tales, and change not only the well-known characteristic style but also the moral thrust of the story: for whether a fairy tale turns out well or not always depends on where you’re standing.

Although this is not a picture book in the conventional sense, the illustrations by Sybille Hein are far more than decorative trifles. With her unique style, the book’s illustrator adds to the story, illustrating it in the best possible sense of the word with chalk drawings filled in with watercolour. The pages are peopled by all kinds of absurd figures, and passages of text are often integrated, collage-like, into the illustrations. All sorts of witty details will delight readers and listeners who enjoy the book together: there’s a dragon with three heads, but who only wears glasses on one head; or a tree whose trunk has a large sign attached to it saying: “trunk”. Here, too, Sybille Hein indulges her faintly anarchic style, and it suits this unusual book down to the ground.

Thus begins Marjaleena Lembke’s modern fairy tale, which has searching as its central theme: there’s the writer who’s searching for ideas, and the fairy tale figures who are searching for their author. Interwoven with this are questions about the relationship between the fictive world and reality. It’s a fairy tale that on the one hand sticks to the rules of the fairy tale genre – but at the same time, it works on the Russian doll principle, in that it opens up a whole series of different narrative levels before managing to tie them all together at the end.

The story begins, as we know, in the royal fairy tale palace: the family are having breakfast and, as usual, are waiting to be served their coffee by their countless servants. But all of a sudden the servants stop moving. The writer has clearly stopped writing, so the figures don’t know what they are supposed to do next. The castle starts to feel chilly, so the family decide to go and try to sort things out for themselves.

The family undertake this journey of discovery in the real world outside the fairy tale: in the modern world with its shopping centres and workers’ demonstrations. However, it quickly transpires that the ‘real’ people are only aware of the fairy tale figures – and the other invented figures – when they encounter them in books. What a frustrating experience for a royal family!

The book alternates between the main story and short interludes of a parallel plot concerning the dilemma of the writer whose inspiration has failed him. He wanders around despondently, and meets an old tramp in the park, whose simple logic and wisdom reveal the true purpose of fairy tales to the writer: fairy tales exist so that we can dream – and such dreams make us a little happier. And, moreover, you must finish what you started!

But let’s return to our royal family. In the town are all sorts of characters wandering around homeless because they were only allowed to appear fleetingly in their stories before being crossed out. Page Thirteen is one such boy; he wasn’t even given a name as he was so unimportant. But the Princess finds him quite charming! The fate of the poor children moves the King and his family, and so they decide to take the homeless children with them; they intend to to return to the castle with the help of the somewhat inscrutable Count von Mnemonic and to dictate their own lives from now onwards. But, naïve as fairy tale characters tend to be, they fall into the Count’s trap: he’s a fairy tale children-catcher and, moreover, one who spends his whole time typing stories into his computer only to delete them all again. But fortunately Page Thirteen is a cunning street child, and he manages to free them all again with the help of the writer. Together they move in to the castle, and the writer finally manages to write a story which has a place for everyone.

With her fairy tale, Marjaleena Lembcke has created a multi-layered and original collage of well known fairy tales and stories. In them, a delight in using quotations is ideally accompanied by something perfectly suited to children: a capacity to turn something familiar into something unfamiliar. By doing this, she has written a quite new fairy tale (as the tramp says: “There’s bound to be some fairy tale out there somewhere that doesn’t exist yet”) with an open ending. Ultimately, what we find is a fairy tale within a fairy tale, in which the figures are constantly discussing the subject of fairy tales, along with the relationship between “poetry” and “truth”. And, of course, Lembcke’s figures relate to the traditional canon of fairy tale values just as much as did those in her story’s predecessors. Thus the fate of the “Little Mermaid” is invoked for upbringing purposes just as much as the wicked stepmother from “Snow White”.

As befits the genre, the fairy tale figures are entirely representative of types rather than being individuals. However, their individual dealings with language constitute the particular comedy of Lembcke’s fairy tale. Whilst the King carries on using his peculiar kingly expressions, the vocabulary of his wife and daughter changes very quickly, and they adapt to their changed situation linguistically. Particularly amusing is the episode when the street children are assigned the task of telling fairy tales, and change not only the well-known characteristic style but also the moral thrust of the story: for whether a fairy tale turns out well or not always depends on where you’re standing.

Although this is not a picture book in the conventional sense, the illustrations by Sybille Hein are far more than decorative trifles. With her unique style, the book’s illustrator adds to the story, illustrating it in the best possible sense of the word with chalk drawings filled in with watercolour. The pages are peopled by all kinds of absurd figures, and passages of text are often integrated, collage-like, into the illustrations. All sorts of witty details will delight readers and listeners who enjoy the book together: there’s a dragon with three heads, but who only wears glasses on one head; or a tree whose trunk has a large sign attached to it saying: “trunk”. Here, too, Sybille Hein indulges her faintly anarchic style, and it suits this unusual book down to the ground.

Translated by Helena Kirkby

By Heike Friesel