Ulrich Raulff

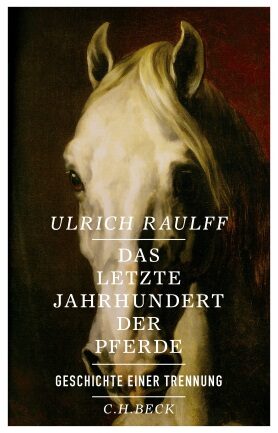

Das letzte Jahrhundert der Pferde. Geschichte einer Trennung

[The last century of the horse. The history of a separation]

- C.H.Beck Verlag

- Munich 2015

- ISBN 978-3-406-68244-5

- 461 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Ulrich Raulff

Das letzte Jahrhundert der Pferde. Geschichte einer Trennung

[The last century of the horse. The history of a separation]

Sample translations

What are we human beings without horses?

Ulrich Raulff's masterful history of a long-inseparable team

The "History of separation," Raulff's subtitle for his broad study of horses, covers all essential areas of human existence, treating economic, technological, political and cultural questions as well as the psychological affinities that have become more opaque since human beings lost their most important non-human partners. Naturally, there are horse racing and horse breeding, these intelligent animals are still used for therapy and for hobby, and the number of horses in Europe is beginning to increase again after its historical low in the 1970s. Nonetheless, Raulff proposes, something fundamental has changed. The "Centaurian pact," which had been maintained for centuries, no longer holds in the same form, at least not in Europe. With the industrialization of agriculture, one of the central farm animals lost its job, and since political rulers no longer ride into cities on horseback, a major signifier of power has disappeared.

Raulff has divided his account of the dissolution of the Centaurian pact into four systematic chapters. The first, "real-life stories," sums up the everyday existence of horses and human beings' coexistence with this supplier of energy in the city and the country, from the horse-drawn carriages of Paris to the invention of threshers for agriculture. The second chapter is devoted to "stories of knowledge" and focuses on specialist books about breeding, literature and painting, places like stud farms and race tracks, social groups like veterinarians and soldiers, and activities like training and breeding, which underscores the central importance of the Arabian horse. The third section is concerned with "stories of metaphors and images," the representations with which "the nineteenth century developed its conceptions of power, freedom, greatness, pity and terror," from Napoleon to Nietzsche, from the erotic connotations of riding and the whip to human pity with dying horses during the First World War. In the fourth and final section, Raulff tells the "histories" of people and horses, inverting his perspective. After "energy, pathos and knowledge," the fourth chapter is about "what the horse teaches us." The horse stories collected here, which include historian Reinhart Koselleck's term "the age of the saddle," recent methodologies in archaeology and tales of cowboys and Indians, is perhaps the best expression of this book's sympathetic, horse-friendly narrative approach.

In general, Raulff - whose publications of the Stefan George Circle and the history of theory in the 1970s have enjoyed great success - is not interested in creating one central "history" but rather a group of decentralized "horse stories," even if a certain focus on important white men on horseback (Napoleon) persists. The role of women - the "her-story" in the human-horse team - is discussed but could have been treated more extensively. For instance, Raulff only devotes a sub-chapter to the mythologically and psychologically so significant figure of the horse-riding Amazons – tellingly it’s entitled "Little Amazons." But the great achievement of this elegant and readable history of horses is that Raulff allows us to see the dialectic of disappearance and re-emergence. While horses seemingly disappear without a sound from everyday life during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they reappear just as forcefully in human dreams and texts, in pictures and on movie screens. This process of sublimation makes horses into "ghosts of modernity."

"What happens," asks Raulff, "if the most important non-human body in which human beings have rightly and wrongly seen themselves reflected is no longer there for its former companion and friend?" but Raulff himself points out that horses haven't disappeared entirely. Not only are they present as ghosts. They also continue to exist around us in the full beauty of equine corporeality. The Last Century of the Horse may be a look back in many respects, but it also opens our eyes to a new understanding of history - and to the idea of humans as living beings surrounded by other entities. History is made not only by men but by animals. "The horse, for six thousand years the creature that moved us," writes Raulff, "is still a great mover of our minds. It's our friend, our companion, our teacher."

Translated by Jefferson Chase

By Jutta Person

Jutta Person, born 1971 in South Baden, studied German, Italian and Philosophy in Cologne and Italy, and gained a doctorate with a dissertation on the history of physiognomy in the 19th century. A journalist and cultural commentator, she is based in Berlin and writes for the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Die Zeit and Philosophie Magazin. From 2004 to 2007 she was an editor at Literaturen; since 2011 she has been in charge of the books section at Philosophie Magazin.

(Updated: 2020)

Publisher's Summary

For ages the horse was humanity’s closest partner. The animal was indispensable to agriculture, connected cities and the countryside, and decided wars. Then the "centaurian pact" broke down. In but a century, the horse dropped out of human history, of which it had been an essential part for millennia. In this fervently written book, Ulrich Raulff tells the story of a separation, the separation of man and horse.

Astonishingly, the horse’s departure from human history is a largely ignored phenomenon. Whole libraries worth of histories have been written about the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but almost no one focuses on the horse, which was omnipresent in both Europe and America and which took more than a century – from Napoleon to the First World War – to gradually disappear. Ulrich Raulff covers the entire spectrum of cultural and literary history, coming up with an impressive narrative of an age on the wane and a chapter in the mankind’s departure from the analogue world.

(Text: C.H.Beck Verlag)