Alexander Kluge

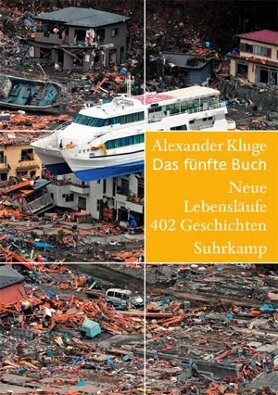

Das fünfte Buch. Neue Lebensläufe - 402 Geschichten

[The fifth book. Case histories. 402 stories]

- Suhrkamp Verlag

- Berlin 2012

- ISBN 978-3-518-42242-7

- 564 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Alexander Kluge

Das fünfte Buch. Neue Lebensläufe - 402 Geschichten

[The fifth book. Case histories. 402 stories]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Russian (2012 - 2014).

Sample translations

Review

Walter Benjamin, said Alexander Kluge in conversation, was to him not a famous dead man, but a close friend, a trustworthy companion, whom he again and again seeks out in spirit, with whom he exchanges views, even though they have never met. It is possible nevertheless that Benjamin, passing through Halberstadt, could once have sat beside Ernst Kluge, theatre-lover and doctor, in the local opera house, from where his son had to fetch him for urgent cases. And even if it is impossible to prove any acquaintance, the chains of cause and effect did pass close by one another. That the dead and the living, yesterday and today are not so firmly distinct but are linked in ways that are difficult to grasp, that they influence and transform each other, is one of the fundamental convictions of the author, born in 1932: After all, “we do not only live in the present”.

In his two-volume ‘Chronik der Gefühle’ (Chronicle of Emotions) of 2000, Kluge had already combined what he called Basisgeschichten – grassroots or foundation stories - and political and historical ones, had in successive short texts drawn a map of his own life and, in a kind of cross-mapping method, laid it over other life-maps. In 2003 another 500 stories appeared in ‘Die Lücke, die der Teufel lässt’ (a selection was published in English as ‘The Devil’s Blind Spot’), and in 2006 a further 350 stories in ‘Tür an Tür mit einem anderen Leben’.

The most recent volume of this unique project, published in 2012, bears the programmatic title ‘The Fifth Book. New Case Histories’ and contains 402 invented and found stories which are in dialogue with the preceding books and have as their subject the “rumble of a world swallowed up, the resilience of human labour and of love politics”, “cold current” and the “invisible writing of our ancestors”. Because it’s not only “people whose lives run a course, but also things: clothes, work, habits and expectations. For humans the course of their lives is a dwelling when there is crisis outside. The courses of all lives together form an invisible text. They never live alone. They exist in groups, generations, states, networks. They love detours and loopholes. The courses of lives are linked creatures.”

A lawyer who worked for Adorno and Fritz Lang and has written both sociological and film theory texts, Kluge also traces the invisible writing of our ancestors in his TV productions, in interviews and films. His approach to the world, drawing on the most diverse fields and subject areas, not reliant on given patterns of experience, is also reflected in the form and structure of his literary work.

And so the “Fifth Book” does not offer a linear narrative, a conventional sequence of texts and pictures, but develops an altogether distinctive, associative interplay of photographs, drawings, illustrations, family portraits, headings, picture legends and narrative forms. Anyone opening the volume at random finds himself entering a complex system of references, an album linking remote areas of life and knowledge, the texts of which bear successive titles such as “An observation by Niklas Luhmann in response to a remark by Richard Sennett”, “A libidinous reason for matter-of-factness”, “Figaro’s loyalty”.

The book’s wealth of representations and diversity of links demonstrate what a richness of forms this old medium has to offer even in the age of the E-book and the Internet. As in a kaleidoscope the stories, observations and references constantly give rise to new constellations, which are not limited to the current volume but also include earlier books, allowing a kind of Klugean universe to emerge, in which an insertion about Heidegger’s journey to Greece links up with the chapter ‘Heidegger in the Crimea’ in ‘Chronicle of Emotions’.

The result is no two-dimensional tableau but a multi-layered compendium and panorama of the 20th century that reaches out far beyond this period, into the 17th and 18th centuries, into Antiquity and beyond that to the beginnings of the world. It is not the familiar course of history that here determines the way of the world, it is the interplay of small and great events, of world wars and family dramas, of national crises and miscellaneous news items, of the publication of novels and nuclear experiments. The reader is led down hardly known side-tracks and apparent dead-ends and only finds his way through this tangled labyrinth with its own inner logic, if he himself seeks out paths and prospects, makes links, picks up threads and spins them further.

Kluge’s own Ariadne’s thread is the story of his family, his childhood on the edge of the Harz Mountains during the Third Reich, his parents’ divorce, the destruction of Halberstadt, his hometown, in an air raid, the end of the war. From this vantage point the author looks forward and back, reports on meetings with Adorno and Luhmann, the lifelong collaboration with his sister, tells of his uncle Otto, who was killed in the First World War, of the German family line, the English branch and the ancestors who came to Germany from France. A flow of diverse linguistic, genetic and cultural components, which come together in just one family and determines its genealogical profile:

“The fact that such contrasts do not give rise to civil war in souls and bodies, but are united minute by minute in every pulse-beat, in every heartbeat, is, unlike the state bodies, a reflection of a generous and tolerant constitution extending human rights, written by the genes (on their islands). As a consequence bodies assembled from the variety of such contrasting ancestors contain a kind of spellbook. No encyclopaedia can equal the power of these inscriptions which determine the future.”

And because future, present and past ultimately form a unity then in this volume which ranges far afield and opens up vast perspectives a lengthy discourse on the ‘The Princess of Cleves’, a 17th century novel of court life, reportages on the Japanese flood and nuclear catastrophe (‘Ancient friends of nuclear power’) and the question, which language “will be spoken in 200 million years” all complement one another. Because everything that was ever written, thought or done, has consequences, releases energies, which are discharged in the remotest reactions.

Kluge’s book pursues these clues, reaching as far as the apocalyptic frontier zones of life, the areas where annihilation and death, executions and summary courts-martial, terror and catastrophes rule. For the researcher of history, the researcher of stories, these are also zones of knowledge and discovery, providing information about what can only be revealed under extreme conditions. Polar explorers like Scott of the Antarctic or the German soldiers frozen to death in Russia did not die of cold but of “pointlessness” and “loss of hope”. And where hope ends there life, too, ends. What lives on, however, is memory and story.

In his two-volume ‘Chronik der Gefühle’ (Chronicle of Emotions) of 2000, Kluge had already combined what he called Basisgeschichten – grassroots or foundation stories - and political and historical ones, had in successive short texts drawn a map of his own life and, in a kind of cross-mapping method, laid it over other life-maps. In 2003 another 500 stories appeared in ‘Die Lücke, die der Teufel lässt’ (a selection was published in English as ‘The Devil’s Blind Spot’), and in 2006 a further 350 stories in ‘Tür an Tür mit einem anderen Leben’.

The most recent volume of this unique project, published in 2012, bears the programmatic title ‘The Fifth Book. New Case Histories’ and contains 402 invented and found stories which are in dialogue with the preceding books and have as their subject the “rumble of a world swallowed up, the resilience of human labour and of love politics”, “cold current” and the “invisible writing of our ancestors”. Because it’s not only “people whose lives run a course, but also things: clothes, work, habits and expectations. For humans the course of their lives is a dwelling when there is crisis outside. The courses of all lives together form an invisible text. They never live alone. They exist in groups, generations, states, networks. They love detours and loopholes. The courses of lives are linked creatures.”

A lawyer who worked for Adorno and Fritz Lang and has written both sociological and film theory texts, Kluge also traces the invisible writing of our ancestors in his TV productions, in interviews and films. His approach to the world, drawing on the most diverse fields and subject areas, not reliant on given patterns of experience, is also reflected in the form and structure of his literary work.

And so the “Fifth Book” does not offer a linear narrative, a conventional sequence of texts and pictures, but develops an altogether distinctive, associative interplay of photographs, drawings, illustrations, family portraits, headings, picture legends and narrative forms. Anyone opening the volume at random finds himself entering a complex system of references, an album linking remote areas of life and knowledge, the texts of which bear successive titles such as “An observation by Niklas Luhmann in response to a remark by Richard Sennett”, “A libidinous reason for matter-of-factness”, “Figaro’s loyalty”.

The book’s wealth of representations and diversity of links demonstrate what a richness of forms this old medium has to offer even in the age of the E-book and the Internet. As in a kaleidoscope the stories, observations and references constantly give rise to new constellations, which are not limited to the current volume but also include earlier books, allowing a kind of Klugean universe to emerge, in which an insertion about Heidegger’s journey to Greece links up with the chapter ‘Heidegger in the Crimea’ in ‘Chronicle of Emotions’.

The result is no two-dimensional tableau but a multi-layered compendium and panorama of the 20th century that reaches out far beyond this period, into the 17th and 18th centuries, into Antiquity and beyond that to the beginnings of the world. It is not the familiar course of history that here determines the way of the world, it is the interplay of small and great events, of world wars and family dramas, of national crises and miscellaneous news items, of the publication of novels and nuclear experiments. The reader is led down hardly known side-tracks and apparent dead-ends and only finds his way through this tangled labyrinth with its own inner logic, if he himself seeks out paths and prospects, makes links, picks up threads and spins them further.

Kluge’s own Ariadne’s thread is the story of his family, his childhood on the edge of the Harz Mountains during the Third Reich, his parents’ divorce, the destruction of Halberstadt, his hometown, in an air raid, the end of the war. From this vantage point the author looks forward and back, reports on meetings with Adorno and Luhmann, the lifelong collaboration with his sister, tells of his uncle Otto, who was killed in the First World War, of the German family line, the English branch and the ancestors who came to Germany from France. A flow of diverse linguistic, genetic and cultural components, which come together in just one family and determines its genealogical profile:

“The fact that such contrasts do not give rise to civil war in souls and bodies, but are united minute by minute in every pulse-beat, in every heartbeat, is, unlike the state bodies, a reflection of a generous and tolerant constitution extending human rights, written by the genes (on their islands). As a consequence bodies assembled from the variety of such contrasting ancestors contain a kind of spellbook. No encyclopaedia can equal the power of these inscriptions which determine the future.”

And because future, present and past ultimately form a unity then in this volume which ranges far afield and opens up vast perspectives a lengthy discourse on the ‘The Princess of Cleves’, a 17th century novel of court life, reportages on the Japanese flood and nuclear catastrophe (‘Ancient friends of nuclear power’) and the question, which language “will be spoken in 200 million years” all complement one another. Because everything that was ever written, thought or done, has consequences, releases energies, which are discharged in the remotest reactions.

Kluge’s book pursues these clues, reaching as far as the apocalyptic frontier zones of life, the areas where annihilation and death, executions and summary courts-martial, terror and catastrophes rule. For the researcher of history, the researcher of stories, these are also zones of knowledge and discovery, providing information about what can only be revealed under extreme conditions. Polar explorers like Scott of the Antarctic or the German soldiers frozen to death in Russia did not die of cold but of “pointlessness” and “loss of hope”. And where hope ends there life, too, ends. What lives on, however, is memory and story.

Translated by Martin Chalmers

By Matthias Weichelt

Matthias Weichelt is Editor-in-Chief of the journal Sinn und Form. He writes for a number of publications including the "Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung" and the "Neue Zürcher Zeitung".