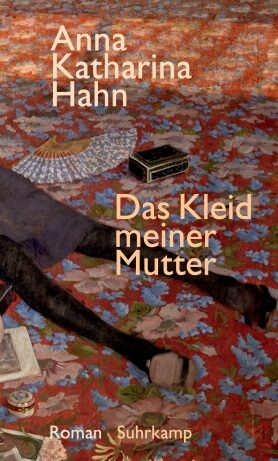

Anna Katharina Hahn

Das Kleid meiner Mutter

[My Mother’s Dress]

- Suhrkamp Verlag

- Berlin 2016

- ISBN 978-3-518-42516-9

- 312 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Anna Katharina Hahn

Das Kleid meiner Mutter

[My Mother’s Dress]

Sample translations

“A vessel of desires and fears”

Anita’s brother Ángel has been living in Germany, allegedly to teach at the university in Berlin. In reality, he has been earning his living as a construction worker. Meanwhile, Anita has returned to live in her parents' apartment, both her mother and father, Oscar and Blanca, are people with style and culture. The father was literary editor at a major Spanish daily.

One hot day in August 2012, Anita discovers her parents in their bed, both dead. When she returns to her parents’ bedroom three days later, she finds the two corpses have disappeared – at least that’s what she thinks. Their clothing is lying in a heap on a chair. "I picked up my mother's purple dress by the fingertips to fold it. Then I saw her. Tiny, smooth, glowing rosy, the hem of her slip concealing her chaste nakedness. She was as large as a doll."

Anna Katharina Hahn remarked in an interview that she had actually dreamt the scene depicted above, and had wanted to turn it into a short novella. Clearly the material expanded in a variety of different directions. The result is a 300+ page novel: a book filled with wild fantasies and ideas, wherein the boundaries between imagination, reality, and folly are consistently and purposely being blurred.

In her first two remarkable novels, Anna Katharina Hahn has proved herself a specialist in the tortuous fears and neuroses of the German middle class, whose epicenter. perhaps not coincidentally, can be located in the well-off and bourgeois city of Stuttgart, where the author also happens to live. Hahn has relocated her novel to present day Spain – ultimately ending up in Swabia through a detour.

Piece by piece, Anna Katharina Hahn eschews a realistic narrative, while ensuring that her novel never loses its footing. Anita does not inform the authorities, or her brother, about her parents’ death. She puts on Blanca’s dress and, in so doing, slips into her mother’s skin and life. When she wears the dress, she is no longer herself, nor is she herself in her surroundings. Anita transforms into Blanca and dives into a complex web of love relationships that have a number of historical implications. It requires technical mastery and a clear and lucid language to keep track of all these narratives. Anna Katharina Hahn is a master of her craft. Initially, she scatters various references and traces along the lines of Grimm’s fairytales and black romanticism, and this motif complex increasingly takes over the narrative.

A good example of this can be seen in one of the central characters of the novel: the writer Gert de Ruit, who apparently had played an important role in both parents' lives. He is a mythical figure. There are no photos of him, except for a photo taken during a meeting of the Group 47. All we are able to see of him is a blur and his foot in a boot (!) De Ruit, born in 1930, the son of German parents and living in Spain, is Anna Katharina Hahn’s most lustfully composed vessel of collective wishes and fears. She pieces together an intricate path to his biographical background that not only leads back to Germany, back to the middle class, but also back to National Socialism.

Admittedly, this all sounds rather implausible. But it is not. The novel is consistent and highly literary, while keeping open the possibility to be read as a story fueled by the Spanish heat, and as a figment of the overwhelmed and burnt out Anita’s mind. Anna Katharina Hahn must have had a lot of fun in weaving a vast web of literary allusions and references. Ludwig Tieck meets Will Vesper meets Roberto Bolano. Not all paths in this novel lead to an end, yet all in all, they create an atmosphere: The dark disquiet of contemporary Madrid, much like the Swabian past, has a common underlying cause that ultimately has to do with politics and moral squalor. This is why „Das Kleid meiner Mutter" is more than just a game.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

By Christoph Schröder

Christoph Schröder, born 1973, lives and works as a freelance author and reviewer in Frankfurt am Main. Among others, he writes for ZEIT, Deutschlandfunk and SWR Culture.

Publisher's Summary

Madrid in the summer of 2012: the repercussions of the latest economic crisis are blatantly obvious in the capital. The young woman Ana María, called Anita, belongs to the »lost generation« that is being denied every possibility of a self-determined existence. Her brother, with a PhD in German studies, has moved on to Berlin to make a living off construction work. Out of necessity, Anita has moved back into her childhood home.

The only things that provide her with stability are her family and her friends, who share her fate of chronic unemployment, and the regular demonstrations on the Puerta del Sol in the heart of the overheated capital. But everything bad can become worse: One day, Anita’s parents are found dead in their shared apartment. Without intending to, Anita becomes entangled in her mother’s life. All she has to do is slip into one of her mother’s dresses and everyone – even her mother’s mysterious German lover – mistakes her for Blanca. Whose everyday life is much more exciting than could ever have imagined: »It felt good to be my mother. I was beautiful, in a way that was strange to me… I even saw some women’s faces light up.«

In her third novel, Anna Katharina Hahn boldly targets one of the most pressing problems of our times: My Mother’s Dress is a fantastic generational and romantic novel from the times of the Euro crisis and at the same time, it is poetic global theatre that moves between Spain, Berlin and Stuttgart. In the end, almost all the loose threads seem to point towards a writer shrouded in mystery, who is said to stop at nothing. But maybe this is also a mere illusion.

(Text: Suhrkamp Verlag)