Paolo Friz

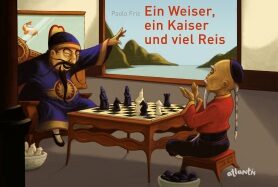

Ein Weiser, ein Kaiser und viel Reis. Von der Erfindung des Schachspiels

[A Wise Man, an Emperor, and a Great Deal of Rice. On the Invention of Chess]

- Atlantis Verlag

- Zurich 2017

- ISBN 978-3-7152-0724-7

- 27 Pages

- 4 Suitable for age 5 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

18 trillion grains of rice

No matter how we choose to approach Paolo Friz’s picture book Ein Weiser, ein Kaiser und viel Reis [A wise man, an emperor, and a great deal of rice], it takes us by surprise at every turn. We can read it as an oriental fairy tale, or regard it as the re-telling of the legend about the invention of chess - but whatever else it may be, it is certainly a parable about poverty and riches, about greed and stupidity, and about the cleverness of a wise old man who manages through a combination of amiability and wiliness to force - or rather: manoeuvre - an emperor blinded by his own sense of omnipotence into making a crucial concession to his people, with the result that justice prevails at long last in his land. The key to the emperor’s volte-face is that the wise old man confronts him with a mathematical puzzle that teaches him a much-needed lesson.

For the eyes of children as well as adults, the eternal message in praise of human dignity, justice and humility is conveyed so clearly in this story that it is a delight to read it and to immerse oneself in the illustrations. The message transcends both time and place. It was just as valid in lands of old as it is in our complex present, regardless of the continent or faith-world that we happen to inhabit.

The illustrator Paolo Friz underscores this message with a fascinatingly stripped-down pictorial aesthetic using digital mixed media, just as the writer Paolo Friz conveys it by using simple but incisive language - as in the story’s opening sentence: ‘Calm lay the great river in the morning light.’ His method here is to place the text - sometimes accompanied by separate mini-illustrations - in plain view on one or other side of his double-page illustrations. ‘The peasants loaded up their boats and took their harvest of rice to the palace to hand over the portion demanded by the emperor’, says the text, and we see how the rice-laden junks move along a broad, yellow-coloured river flanked by bizarre rock formations towards the palace nestling in its well protected bay. To lend a greater sense of depth to the image whilst also disrupting the otherwise seemingly harmonious ambience, Friz inserts in one corner of the foreground a menacing little fragment abstracted from some other world: a bat dangling from a gingko branch, with a caterpillar sneaking into the picture right next to it.

Thus Paolo Friz continually opens up new and surprising perspectives on the events of the story. Sometimes fairytale landscapes unfold before us, sometimes we see the palace interiors peopled with the emperor and his court, and then - as though in a well cut film - we see close-ups detailing the facial features of the characters. To top things off, the wise old man confronts the emperor, and us the readers, with an astonishing mathematical puzzle.

For the emperor refuses to grant the request of the poverty-stricken peasants to allow them a larger share of rice than before. The hungry peasants then turn for help to a wise old inventor. He agrees to help them, and teaches the emperor - who loves playing board games - a new one: chess. But the wily old inventor lets the emperor keep the new game on one condition: ‘I want one grain of rice for the first square on the board, two grains for the second, four for the third, eight for the fourth, and so on. In other words, twice as many each time, right up to the sixty fourth square.’ The emperor agrees, thinking that at most he will have to hand over a single sack of rice.

The Court Mathematician having been hurriedly summoned, the results of his calculations are conveyed by Paolo Friz in a breathtaking metaphor: in order to transport the requisite quantity of rice, billions of ships would be needed, and if they were placed end to end the line would be longer than the distance from the earth to the sun! In all, 18 trillion grains of rice, or 900 billion tonnes. The emperor is devastated, falls to his knees, and begs the wise old man for forgiveness. This marks the beginning of a new epoch in the land. - Oh, how wonderful it would be if on occasion the world’s potentates did indeed fall to their knees in the face of the wit and intelligence of the wise!

Translated by John Reddick

By Siggi Seuß

Siggi Seuß, freelance journalist, radio script writer and translator, has been writing reviews of books for children and young people for many years.

Publisher's Summary

The peasants are starving because they have to hand over so much of their rice to the emperor. To meet their dire need a wise old man invents a new game for the emperor - chess. The emperor is thrilled, and as his reward the wise old man asks for 1 rice grain on the first square of the board, 2 on the second, 4 on the third, and so on, right through to the sixty-fourth - thus doubling the quantity on each successive square.

Not until the evening does the emperor become aware that he hadn’t had the least idea of how much rice he had promised the wise old man: a solid line of fully laden ships stretching all the way from the earth to the sun would not be enough carry it all!

The outcome is that the emperor henceforth only receives as much rice as he needs, and no one in the land has to go hungry any more.

(Text: Atlantis Verlag)