Ninon Ammann

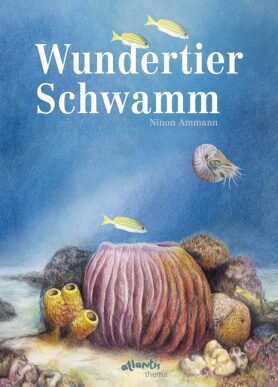

Wundertier Schwamm

[The Wondrous Sponge]

- Atlantis Verlag

- Zurich 2019

- ISBN 978-3-7152-0749-0

- 40 Pages

- 5 Suitable for age 6 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

In the World of Sponges

As the reviewer, let me start by offering a personal confession: This morning I bought a bath sponge for the first time in my life—to be precise it was a “high-quality natural sponge from the Mediterranean Sea.” That’s what it says on the package. The last time I ever personally encountered a natural sponge I was sitting in a bathtub filled with the spruce needle bubble bath of my childhood. My mother scrubbed my back with a sponge she called “genuine” and afterwards I played “underwater tank” with the wet thing. At the time it amazed me that my sponge could absorb a seemingly never-ending amount of water and I imagined that it would probably be enough to put out a wildfire in the Serengeti.

Now the “sustainably harvested natural sponge,” phylum: Porifera, completely cleaned of all shells and sand, is lying in front of me on my desk, inspiring me to review an extraordinary book about extraordinary organisms that we encounter at most in bathtubs, on underwater reports on TV, or in darkened aquariums in zoos. And now also in this book by Ninon Ammann: Wundertier Schwamm (Wondrous Sponges), which is touching in a peculiar way (see above: sponge purchase), shedding light on an almost forgotten world. Fortunately not in the way that many nonfiction nature books do: by offering excessive amounts of information, efficiently using every page up to the very edge of the paper, and dramatically transferring knowledge in a way that falsely assumes the more, the better. It can be done differently, as demonstrated by the Swiss author and illustrator in a balanced mixture of narrative text, informative subheadings for smaller and larger colored illustrations (no photographs!), and scenes of the seafloor that fill entire pages.

We plunge wide-eyed into this mysterious underwater world that in most nonfiction books focuses largely on spectacular fishes, if not sea monsters. But there is yet another world down there, in oceans, but also in lakes and rivers. Who among us has ever seriously considered the fact that the 8000 known species of sponges belong to the animal and not the plant kingdom? Who knows that sponges are among the oldest living beings on our planet, that they were here long before dinosaurs—much less human beings—entered the stage? That was 750 million years ago!

We will never cease to be amazed as we delve page for page deeper into the world of sponges, as Jacques Cousteau once did. Such a diversity of shapes and colors! And their immense importance for the healthy ecology of the oceans: 3000 liters of water are filtered daily by a single sponge the size of a soccer ball. We can truly start to rave about the marvels of nature and the marvel of sponges as presented in this book. And once again we recognize what happens when a habitat, such as the ocean, goes through extreme changes—through warming, insufficient oxygen, or pollution.

Before you start getting a guilty conscience for buying a genuine natural bath sponge: Natural sponges have been used by humans for over two thousand years and today they are cultivated on aquafarms. What I have in front of me, fascinating me with its elegance, its thousands of pores, is the skeleton of a demosponge, composed of soft spongin fibers. From now on I will look at even this modest descendant of one of the first multi-celled organisms on our blue planet with different eyes. And with respect. I promise.

Translated by Allison Brown

By Siggi Seuß

Siggi Seuß, freelance journalist, radio script writer and translator, has been writing reviews of books for children and young people for many years.

Publisher's Summary

The first of its kind!–A children‘s non- fiction book about sponges.And what amazing creatures they are! Ranking with the oldest of all animals, they were around long before the dino-saurs, and by now, there are about 8000 different species of them.They filter water, they‘re known as «the pharmacies of the seas»‘, they are usedas tools by dolphins and they‘ve got an arsenal of nifty tricks to outsmart pre-dators. An endlessly fascinating form of life!

(Text: Atlantis Verlag)