Leif Randt

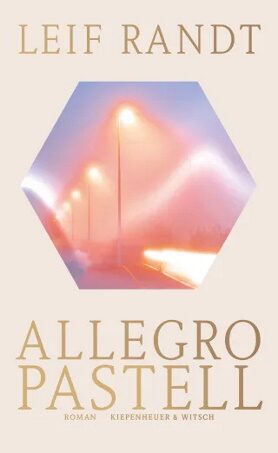

Allegro Pastell

[Allegro Pastell]

- Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag

- Cologne 2020

- ISBN 978-3-462-05358-6

- 280 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

The tristesse of living ‘on trend’

Leif Randt, born 1983 in Frankfurt, had already attracted considerable attention with his novels Schimmernder Dunst über CobyCounty (‘The shimmering haze over CobyCounty’) and Planet Magnon (‘Planet Magnon’), both of which bore dystopian elements that led all and sundry to categorise Randt as a pop-lit author following in the wake of Rainald Goetz and Christian Kracht. The winner of numerous prizes, he is regarded as a writer specialising in the youth scene and in lifestyle-oriented milieus, with a stoical-cum-pragmatic approach in his meticulous recording of the trends, codes and consumer values of our current media-dominated world.

The word ‘Allegro’ in the novel’s title comes from the name of a school in Berlin with a sports centre where Leif Randt plays badminton (like countless other German writers, Randt is a Berliner by choice rather than birth). So, too, does his female protagonist, Tanja, who has just achieved great success with her debut novel on the theme of ‘virtual reality and mindfulness’. Her boyfriend Jerome, who lives in Frankfurt, is a web designer – as is Randt himself in a sideline capacity. Living in their respective metropolises, the pair – both in their early thirties and more or less representing the two sides of Randt’s own personality – conduct a long-distance relationship intended to be ‘beautiful but not existential’. The main focus of the book is on the way the couple contrive to sustain this relationship, which – albeit emotionally tepid – is at no risk from either major rows or tumultuous feelings.

The number-one factor here is the absence of any financial worries; the second is that both of them are fully attentive to the markers of whatever happens to constitute the current zeitgeist, which in turn enable them to constantly curate and re-curate their self-image. But this mode of fashioning their own identity does not serve to widen their horizons, for instance, or to refine their tastes: it simply makes them ever more perfectly alert to whatever products, brands, therapies, travel destinations, pubs, clubs, drugs etc. count at any given moment as especially prestigious. One such instance is the mode of communication – heavily larded with anglicisms – that is used excessively on all digital channels, and which doesn’t serve to facilitate understanding or resolve disagreements, but instead just churns out jargon and status-messages – which Leif Randt highlights by putting them in italics. Even where the characters engage in self-reflection – the key issue in a large proportion of the messages exchanged in the book – they never penetrate beyond the most superficial level of whatever is trendy, and so never make any progress.

The extent to which readers recognise familiar patterns, and hence also the extent of their enjoyment, will depend on the milieu and the generation they belong to - but no one can fail to notice the tristesse lurking within this pastel-coloured world of mediocrity when a minor flare-up finally causes the relationship to collapse – and with a whimper rather than a bang, just like everything else that preceded it. While deploying an ostensibly simple kind of language, Leif Randt has produced a novel rich in ambiguities that reflects a particular aspect of today’s Germany – though we have to hope that it is only one aspect among many.

Translated by John Reddick

By Kristina Maidt-Zinke

Kristina Maidt-Zinke is a book and music critic at the Süddeutsche Zeitung and also writes reviews for Die Zeit.

Publisher's Summary

Tanja Arnheim, whose debut novel enjoys cult status, is turning 30 in a few weeks. Looking out onto Berlin’s Hasenheide park, she waits for an earth-shattering idea for her new book. Her boyfriend, the sought-after web designer Jerome Daimler, is in his mid-30s and lives in his parents’ bungalow in the countryside. Increasingly, he’s trying to understand his life as spiritual contemplation. Despite their long-distance relationship, Tanja and Jerome always stay close through texts and images. And they visit each other in their respective realities for long weekends: Their relationship is an attempt to be there for – but not lost to – each other. Their parents, friends and depressed siblings reflect a suffering to which Tanja and Jerome largely remain immune. Yet the desire to preserve their affection without letting it grow staid or painfully existential poses a major challenge for the couple.

Allegro Pastell is the story of a seemingly normal love and its transformations. A novel in three phases that begins in the recordbreakingly hot spring of 2018.

(Text: Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag)