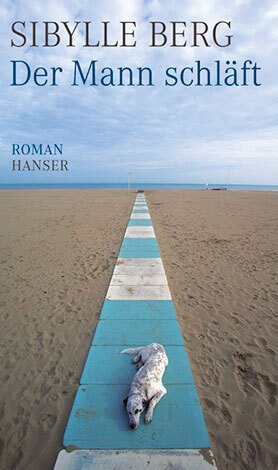

Sibylle Berg

Der Mann schläft

[Man, asleep]

- Carl Hanser Verlag

- München 2009

- ISBN 978-3-446-23388-1

- 310 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Sibylle Berg

Der Mann schläft

[Man, asleep]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Spanish: Argentina (2009 - 2011).

Sample translations

Review

Born in Weimar and living in Zurich, Sybille Berg is known as the Cassandra of the slapstick era, as an expert on ennui, as the only unflinching propagandist of Vanitas thought in Germany’s literary scene. End’s Well (Ende gut) is the title of her all-around critique of the disaster area Germany, which four years before the financial crisis began, had reached an apocalyptic conclusion. Nonetheless, there was the utopian escape to Finland which justified the novel’s title.

The next Berg work, The Journey (Die Fahrt), gave us a diverse group of characters wandering aimlessly through a ruined globe; the man-made misery zones are depicted with an inimitable lust for the despicable. But the author has never denied that her melancholic diagnoses of downfall and futility are merely the flip side of a deep longing for beauty and goodness, for kindness and humanity.

In her latest epic, The Man’s Asleep (Der Mann schläft) she cloaks this yearning in soft, melancholic, moderately malicious images. The heroine, a nondescript middle-aged woman who earns her living by writing instruction manuals, recognizes, in retrospect, that she has found something precious and lost it again - a special, even odd kind of love. In other words, not "what the French films have shown us, desire, conversations for nights on end about feelings, hoping to reawaken the passion, sex under rain-drenched street lamps, lots and lots of suffering, and, in the end, silently sitting in a French kitchen. This is not what went missing here, rather it was a love "that was calm and quiet, that was friendly and exuded a certain sweetness.”

The story begins in a vaguely Swiss region, where the world hasn’t yet been destroyed or gone dark, though it is dark gray, damp and washed out. In any case, as the first chapter title reveals, it was "in the winter back then. Four months ago". And yet, according to the narrator, all was well with the world, because: "Every morning I stood in front of the door and was happy I had survived the night; that all the houses were still where they belonged; and the man lay in bed.”

This slight, modest happiness does not last for long. The story moves back and forth on a fictional timeline between "Back then”. Four years ago," and the changing times of the day—of a certain "today"—through to the "now ', in which the narrator is standing on the dock of a Chinese vacation island, feeling like a " a clump of organic tissue," a toxic orange sunset before her eyes and her brain bathed in French white wine, which helps her to "forget the incredible boredom that comes with trying to get her life in order."

The cause of her misery: "The man” suddenly disappeared after about three and a half years of living together. During a vacation on the above mentioned island he does not return from fetching a newspaper. The desperate woman tries to figure out what has happened. She describes the man, explains the nature of their relationship. And since this figure has been created by Mrs. Berg, she also observes the world and offers a running commentary on it: she reports of her encounters with strange and sad individuals, with suicide victims and dysfunctional characters in Europe and China. In each case: "The people had their darling moments, but it did not conceal the fact that most of them were overwhelmingly simple-minded and malicious."

An exception was "the man". He was not handsome, not rich, not particularly charming and not a great speaker, but he was devoted to the woman with a wonderful stoic consistency, and he made little noises while he slept, "which were nicer than all the others before him, because the person making them was somebody I liked, and to make noises he had to be alive, to build a tent for me in the night."

Yet, the woman rebelled against the feelings of security he provided; in the first weeks they were together she threw a night lamp at the man, and in the final hours before he disappeared drove him crazy with her bad mood. But in between, before she had the "unfortunate idea" of taking a long journey, her affection was "like a friendly river that occasionally overflowed." The portrayal of that time is full of poetic and bizarre Berg-apercus that take the clichéd topic of "love" and casts it in a new and oblique light.

Whether the end is good or bad is left for the reader to decide. When some white wine prevents the abandoned protagonist from plunging into the South China Sea, she has a delicate hallucination, which might be seen as a glimmer of hope. In any case, this is the "sweetest" novel Sibylle Berg has written so far – but it beautifully and powerfully proves her reputation as being the last free radical of contemporary German literature.

The next Berg work, The Journey (Die Fahrt), gave us a diverse group of characters wandering aimlessly through a ruined globe; the man-made misery zones are depicted with an inimitable lust for the despicable. But the author has never denied that her melancholic diagnoses of downfall and futility are merely the flip side of a deep longing for beauty and goodness, for kindness and humanity.

In her latest epic, The Man’s Asleep (Der Mann schläft) she cloaks this yearning in soft, melancholic, moderately malicious images. The heroine, a nondescript middle-aged woman who earns her living by writing instruction manuals, recognizes, in retrospect, that she has found something precious and lost it again - a special, even odd kind of love. In other words, not "what the French films have shown us, desire, conversations for nights on end about feelings, hoping to reawaken the passion, sex under rain-drenched street lamps, lots and lots of suffering, and, in the end, silently sitting in a French kitchen. This is not what went missing here, rather it was a love "that was calm and quiet, that was friendly and exuded a certain sweetness.”

The story begins in a vaguely Swiss region, where the world hasn’t yet been destroyed or gone dark, though it is dark gray, damp and washed out. In any case, as the first chapter title reveals, it was "in the winter back then. Four months ago". And yet, according to the narrator, all was well with the world, because: "Every morning I stood in front of the door and was happy I had survived the night; that all the houses were still where they belonged; and the man lay in bed.”

This slight, modest happiness does not last for long. The story moves back and forth on a fictional timeline between "Back then”. Four years ago," and the changing times of the day—of a certain "today"—through to the "now ', in which the narrator is standing on the dock of a Chinese vacation island, feeling like a " a clump of organic tissue," a toxic orange sunset before her eyes and her brain bathed in French white wine, which helps her to "forget the incredible boredom that comes with trying to get her life in order."

The cause of her misery: "The man” suddenly disappeared after about three and a half years of living together. During a vacation on the above mentioned island he does not return from fetching a newspaper. The desperate woman tries to figure out what has happened. She describes the man, explains the nature of their relationship. And since this figure has been created by Mrs. Berg, she also observes the world and offers a running commentary on it: she reports of her encounters with strange and sad individuals, with suicide victims and dysfunctional characters in Europe and China. In each case: "The people had their darling moments, but it did not conceal the fact that most of them were overwhelmingly simple-minded and malicious."

An exception was "the man". He was not handsome, not rich, not particularly charming and not a great speaker, but he was devoted to the woman with a wonderful stoic consistency, and he made little noises while he slept, "which were nicer than all the others before him, because the person making them was somebody I liked, and to make noises he had to be alive, to build a tent for me in the night."

Yet, the woman rebelled against the feelings of security he provided; in the first weeks they were together she threw a night lamp at the man, and in the final hours before he disappeared drove him crazy with her bad mood. But in between, before she had the "unfortunate idea" of taking a long journey, her affection was "like a friendly river that occasionally overflowed." The portrayal of that time is full of poetic and bizarre Berg-apercus that take the clichéd topic of "love" and casts it in a new and oblique light.

Whether the end is good or bad is left for the reader to decide. When some white wine prevents the abandoned protagonist from plunging into the South China Sea, she has a delicate hallucination, which might be seen as a glimmer of hope. In any case, this is the "sweetest" novel Sibylle Berg has written so far – but it beautifully and powerfully proves her reputation as being the last free radical of contemporary German literature.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

By Kristina Maidt-Zinke

Kristina Maidt-Zinke is a book and music critic at the Süddeutsche Zeitung and also writes reviews for Die Zeit.