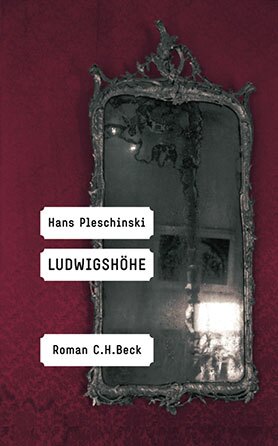

Hans Pleschinski

Ludwigshöhe

[Ludwig’s heights]

- C.H.Beck Verlag

- Munich 2008

- ISBN 978-3-406-57689-8

- 579 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Hans Pleschinski

Ludwigshöhe

[Ludwig’s heights]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Portuguese: Brazil (2007 - 2008).

Sample translations

Review

In his most recent novel Ludwigshöhe, Hans Pleschinski, a two-time winner of Munich’s Tukan award, delivers an incredibly dense, polyphonic and nuanced work of contemporary German literature.

To the surrounding Bavarian community, the Hungarian House on Lake Starnberg seems like an enclave hiding a dark secret: it serves as a hospice, not for the terminally ill in need of professional help during the final months of their life, but for those weary of living under the tragic circumstances of their everyday existence. They are called "finalists", and the siblings Ulrich, Clarissa and Monika Berg reluctantly must provide these people with a quiet and secluded refuge from the outside world to commit suicide. Their uncle’s inheritance, a not too inconsiderable fortune, comes with a single condition: they must offer support to the world-weary. Only when the three siblings fulfill this project within a year will they inherit the money.

The siblings reluctantly take up the challenge and acquiesce to their fate, without enthusiasm, but also without too many moral scruples. They discreetly distribute business cards, and soon thereafter welcome their first “customer". It should hardly come as a surprise that the project comes with a series of rather unexpected complications.

Nonetheless, at least two of the finalists carry out the planned death, quickly and without much ado, while the rest grow increasingly hesitant. And thus the inevitable occurs; the residents get up the courage to live on; living together with like-minded people proves to be the key to feeling understood. The inhabitants have a big party on the way to committing suicide, and celebrate their final days with pompously delivered sandwiches and pastries; apparently, the road to Charon proves an easier ride intoxicated by prosecco. There's just one hitch: The “finalists” are having the time of their lives. And who wants to die when you’re at the top of your game?

The Bergs are forced to actively intervene, they can’t allow anybody to return from the Hungarian House alive, or their illegal activities will be discovered: "Dear guests! determined finalists as we like to call you. For some of you the stay…contrary to expectations…seems to be lasting quite a few days... [...] And, by the way, may we remind you of our cellars that offer ultimate quiet and seclusion for you to act on your unshakeable the good old-fashioned way." Even an increase of the daily allowance to 40 Euros a day does not speed up the dying. The siblings, already strained by the situation, get pushier, increasing the daily fees to 50 Euros and using every means possible to persuade the finalists to commit suicide: "Protect yourself and society from illness, old age, poverty and sorrow." But the more the Bergs harass the finalists, the more they regain their will to survive.

Pleschinskis "finalists," all go through a similar trajectory. Failing to measure up to society’s bourgeois values and norms, they feel they’ve lost their chance to live a self-determined life free of outside forces. Killing themselves offers a last chance to live as an autonomous individual. This goes for the teacher Ute Wimpf, who can’t cope with the spoiled kids anymore, to the Syrian Aizia, who is in hiding from her brothers because she’s in love with a Christian. Isolated from society and pressure from outside, the characters in Ludwigshöhe find their way back to their individuality.

In his novel, which has won the Nicolas Born Award, Pleschinski explores to what extent suicide can be considered an act of individual freedom, and how suicide is discussed and evaluated within society. Pleschinski presents suicide as an absolute negation of life and reality. If we understand self-chosen death as a transcendental act of a self-determined life, Pleschinski caricatures this view by introducing the Berg siblings as an outside authority who make it possible for the suicidal guests to go through with the suicide in reality.

But the Berg’s moral dilemma is also clearly dramatized. When is the desire to commit suicide comprehensible, what are legitimate reasons for doing it? Is there any adequate answer? Pleschinski, who has dealt extensively with the social and literary discourse around suicide, comments in an interview: "This is what I discovered in Ludwigshöhe: Almost every suicide happens too early."

Pleschinski’s social critique is shown through the “finalists” and their unexpected return to life: the only place his characters can enjoy an autonomous and social life is in the enclave of the Hungarian House. Thus, the death wish is simultaneously a conscious rejection of a perverted society, and Ludwigshöhe can be read as a farce about questionable morals and values that are played out here ad absurdum. This is dramatically shown in the little boy Benny, who seeks refuge in the Hungarian House because he’s afraid his bad grades will upset his grandmother. Pleschinski tells his story about "assisted dying" from distance with plenty of humor and sharp-tongued ferocity. The characters are grotesquely drawn and define themselves exclusively by the role they play within the microcosm of the Hungarian House – the suicide discussions are staged as a Theatrum Mundi on Lake Starnberg. One of Pleschinski’s characters sums up the story with the words, "we are what we do and say," thus turning his novel into a meta-fiction. This self-reflexivity of the characters is amazing- given their lack of reflection in relation to their own life. But this isn’t how the novel concludes: After the figures head for the darkness of the cellar--in a kind of religious procession—to carry out their “enough is enough”, they survive in the end after all. Pleschinski consciously refuses to provide an explanation for the rejection of collective suicide.

To the surrounding Bavarian community, the Hungarian House on Lake Starnberg seems like an enclave hiding a dark secret: it serves as a hospice, not for the terminally ill in need of professional help during the final months of their life, but for those weary of living under the tragic circumstances of their everyday existence. They are called "finalists", and the siblings Ulrich, Clarissa and Monika Berg reluctantly must provide these people with a quiet and secluded refuge from the outside world to commit suicide. Their uncle’s inheritance, a not too inconsiderable fortune, comes with a single condition: they must offer support to the world-weary. Only when the three siblings fulfill this project within a year will they inherit the money.

The siblings reluctantly take up the challenge and acquiesce to their fate, without enthusiasm, but also without too many moral scruples. They discreetly distribute business cards, and soon thereafter welcome their first “customer". It should hardly come as a surprise that the project comes with a series of rather unexpected complications.

Nonetheless, at least two of the finalists carry out the planned death, quickly and without much ado, while the rest grow increasingly hesitant. And thus the inevitable occurs; the residents get up the courage to live on; living together with like-minded people proves to be the key to feeling understood. The inhabitants have a big party on the way to committing suicide, and celebrate their final days with pompously delivered sandwiches and pastries; apparently, the road to Charon proves an easier ride intoxicated by prosecco. There's just one hitch: The “finalists” are having the time of their lives. And who wants to die when you’re at the top of your game?

The Bergs are forced to actively intervene, they can’t allow anybody to return from the Hungarian House alive, or their illegal activities will be discovered: "Dear guests! determined finalists as we like to call you. For some of you the stay…contrary to expectations…seems to be lasting quite a few days... [...] And, by the way, may we remind you of our cellars that offer ultimate quiet and seclusion for you to act on your unshakeable the good old-fashioned way." Even an increase of the daily allowance to 40 Euros a day does not speed up the dying. The siblings, already strained by the situation, get pushier, increasing the daily fees to 50 Euros and using every means possible to persuade the finalists to commit suicide: "Protect yourself and society from illness, old age, poverty and sorrow." But the more the Bergs harass the finalists, the more they regain their will to survive.

Pleschinskis "finalists," all go through a similar trajectory. Failing to measure up to society’s bourgeois values and norms, they feel they’ve lost their chance to live a self-determined life free of outside forces. Killing themselves offers a last chance to live as an autonomous individual. This goes for the teacher Ute Wimpf, who can’t cope with the spoiled kids anymore, to the Syrian Aizia, who is in hiding from her brothers because she’s in love with a Christian. Isolated from society and pressure from outside, the characters in Ludwigshöhe find their way back to their individuality.

In his novel, which has won the Nicolas Born Award, Pleschinski explores to what extent suicide can be considered an act of individual freedom, and how suicide is discussed and evaluated within society. Pleschinski presents suicide as an absolute negation of life and reality. If we understand self-chosen death as a transcendental act of a self-determined life, Pleschinski caricatures this view by introducing the Berg siblings as an outside authority who make it possible for the suicidal guests to go through with the suicide in reality.

But the Berg’s moral dilemma is also clearly dramatized. When is the desire to commit suicide comprehensible, what are legitimate reasons for doing it? Is there any adequate answer? Pleschinski, who has dealt extensively with the social and literary discourse around suicide, comments in an interview: "This is what I discovered in Ludwigshöhe: Almost every suicide happens too early."

Pleschinski’s social critique is shown through the “finalists” and their unexpected return to life: the only place his characters can enjoy an autonomous and social life is in the enclave of the Hungarian House. Thus, the death wish is simultaneously a conscious rejection of a perverted society, and Ludwigshöhe can be read as a farce about questionable morals and values that are played out here ad absurdum. This is dramatically shown in the little boy Benny, who seeks refuge in the Hungarian House because he’s afraid his bad grades will upset his grandmother. Pleschinski tells his story about "assisted dying" from distance with plenty of humor and sharp-tongued ferocity. The characters are grotesquely drawn and define themselves exclusively by the role they play within the microcosm of the Hungarian House – the suicide discussions are staged as a Theatrum Mundi on Lake Starnberg. One of Pleschinski’s characters sums up the story with the words, "we are what we do and say," thus turning his novel into a meta-fiction. This self-reflexivity of the characters is amazing- given their lack of reflection in relation to their own life. But this isn’t how the novel concludes: After the figures head for the darkness of the cellar--in a kind of religious procession—to carry out their “enough is enough”, they survive in the end after all. Pleschinski consciously refuses to provide an explanation for the rejection of collective suicide.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

By Jennifer Endro