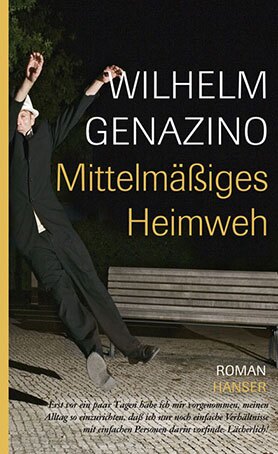

Wilhelm Genazino

Mittelmäßiges Heimweh

[Mediocre homesickness]

- Carl Hanser Verlag

- Munich 2007

- ISBN 978-3-446-20818-6

- 189 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Wilhelm Genazino

Mittelmäßiges Heimweh

[Mediocre homesickness]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Portuguese: Brazil (2007 - 2008).

Sample translations

Review

It all begins as usual and exactly as we have come to expect it from Wilhelm Genazino, the master of micro-realism: In the evening, a lonely, middle-aged man roams through the streets of an un-named city. Being a shrewd observer of the everyday, he contemplates what he sees along the way. In the very beginning of Genazino’s new novel Mediocre Homesickness, he formulates literally “en passant” that “it is not easy to be a loner,” an insight that is fundamental not only to himself.

Thus, he tries to escape his separation and seeks refuge in a bustling, nearby bar where just then the European soccer championship game between Germany and the Czech Republic is being broadcast. He remains a foreign body even in this crowd, how-ever, - and, as he notices with horror, a damaged one at that. For among the cries of the fans and the general outrage about the opposing team’s goal his left ear has dropped off unnoticed. There it now lies under the table, regarded by no one.

The shocking aspect of this “unheard-of event” is not the loss of the ear itself but both the way in which the afflicted uncomplainingly accepts his fate and the disregard of his loss by his surroundings. “Such a small deficiency no longer draws attention in a world overcrowded by shrillness,” the first-person narrator Dieter Rotmund states laconically and with the same lack of pity he displays toward himself as toward others.

The invasion of the inexplicable into a hitherto orderly middle-class life is told throughout from the perspective of this man who works as a controller for a pharmaceutical company. The ear, lost bloodlessly and without pain, will not be the only loss he will have to mourn: Soon after the ear, his wife, together with his daughter, also leaves him; subsequently, his right little toe follows when it falls off in the pool for no apparent reason. And all this happens when Rotmund had just decided to arrange his “days in such a way that I will find myself only in simple relationships with simple people.”

Much to his chagrin, this plan fails miserably. The reader becomes a delighted witness of Rotmund’s all the more humorous and insightful attempts to preserve the alleged status of normalcy and to accommodate himself in his new circumstances as well as may be.

Particularly convincing in Genazino’s tight narrative is the way in which he succeeds time and again to draw a spark of wit from despair itself. Genazino absorbs his protagonist’s misanthropic constitution by means of a subtle humor that finds comedy in failure without ever denouncing his character. Rather, he creates in Rotmund a believable embodiment of the difficult art of taking life as it is and not to give into the desperation that ever again causes this “nomad in the land of love, weary of all experience” to burst into tears (not with-out quiet pleasure.)

After losing the ear and suffering the failure of his already mediocre marriage, Rotmund finds himself in situation characterized by the opposite trends of career advancement (unexpectedly and unenthusiastically he finds himself promoted to finance director) and private decline. This culmination is reflected symbolically in the physical as well as emotional dissociation experienced by this tragicomic hero who forever grinds right past a full blown depression.

Thus, Rotmund considers himself a “ruin of love” and yet he knows only to counter the emptiness of his life with a renewed search for love, even if he is aware of the inevitable disappointments. “At the same time I know that I will die off if I can not take root in a new woman.” Consequently, whether willing or unwilling, he enters into an extremely humble sexual relationship with Sonya, his apartment’s previous renter. Significantly, she, too, is maimed in body and soul: she has but one breast left and survives as a con artist. In Rotmund’s general world, damages are on the rise (the newspaper reports about a child who lost a thumb;) – In his mind, all these are harbingers of an advancing catastrophe, approaching unnoticed.

Paradoxically, Genazino is able to paint the consciously exaggerated, and yet strangely plausible picture of a monstrous present by making Rotmund’s distorted perceptions absolute. In his quiet despair and with the melancholic view of the outsider, Rotmund ever again coins aperçus of aphoristic clarity. Seemingly unnoticed by himself, these are embedded in Rot-mund’s unending stream of thought. “How strange is an ear! You have to lose one to notice how unusual life was with two ears.”

As we others will assumedly be spared this experience, we are able to value Rotmund’s existential insights all the more. We appreciate the aesthetic delight of reading these insights that gain their comic quality in the very desolation that gives rise to them.

Thus, he tries to escape his separation and seeks refuge in a bustling, nearby bar where just then the European soccer championship game between Germany and the Czech Republic is being broadcast. He remains a foreign body even in this crowd, how-ever, - and, as he notices with horror, a damaged one at that. For among the cries of the fans and the general outrage about the opposing team’s goal his left ear has dropped off unnoticed. There it now lies under the table, regarded by no one.

The shocking aspect of this “unheard-of event” is not the loss of the ear itself but both the way in which the afflicted uncomplainingly accepts his fate and the disregard of his loss by his surroundings. “Such a small deficiency no longer draws attention in a world overcrowded by shrillness,” the first-person narrator Dieter Rotmund states laconically and with the same lack of pity he displays toward himself as toward others.

The invasion of the inexplicable into a hitherto orderly middle-class life is told throughout from the perspective of this man who works as a controller for a pharmaceutical company. The ear, lost bloodlessly and without pain, will not be the only loss he will have to mourn: Soon after the ear, his wife, together with his daughter, also leaves him; subsequently, his right little toe follows when it falls off in the pool for no apparent reason. And all this happens when Rotmund had just decided to arrange his “days in such a way that I will find myself only in simple relationships with simple people.”

Much to his chagrin, this plan fails miserably. The reader becomes a delighted witness of Rotmund’s all the more humorous and insightful attempts to preserve the alleged status of normalcy and to accommodate himself in his new circumstances as well as may be.

Particularly convincing in Genazino’s tight narrative is the way in which he succeeds time and again to draw a spark of wit from despair itself. Genazino absorbs his protagonist’s misanthropic constitution by means of a subtle humor that finds comedy in failure without ever denouncing his character. Rather, he creates in Rotmund a believable embodiment of the difficult art of taking life as it is and not to give into the desperation that ever again causes this “nomad in the land of love, weary of all experience” to burst into tears (not with-out quiet pleasure.)

After losing the ear and suffering the failure of his already mediocre marriage, Rotmund finds himself in situation characterized by the opposite trends of career advancement (unexpectedly and unenthusiastically he finds himself promoted to finance director) and private decline. This culmination is reflected symbolically in the physical as well as emotional dissociation experienced by this tragicomic hero who forever grinds right past a full blown depression.

Thus, Rotmund considers himself a “ruin of love” and yet he knows only to counter the emptiness of his life with a renewed search for love, even if he is aware of the inevitable disappointments. “At the same time I know that I will die off if I can not take root in a new woman.” Consequently, whether willing or unwilling, he enters into an extremely humble sexual relationship with Sonya, his apartment’s previous renter. Significantly, she, too, is maimed in body and soul: she has but one breast left and survives as a con artist. In Rotmund’s general world, damages are on the rise (the newspaper reports about a child who lost a thumb;) – In his mind, all these are harbingers of an advancing catastrophe, approaching unnoticed.

Paradoxically, Genazino is able to paint the consciously exaggerated, and yet strangely plausible picture of a monstrous present by making Rotmund’s distorted perceptions absolute. In his quiet despair and with the melancholic view of the outsider, Rotmund ever again coins aperçus of aphoristic clarity. Seemingly unnoticed by himself, these are embedded in Rot-mund’s unending stream of thought. “How strange is an ear! You have to lose one to notice how unusual life was with two ears.”

As we others will assumedly be spared this experience, we are able to value Rotmund’s existential insights all the more. We appreciate the aesthetic delight of reading these insights that gain their comic quality in the very desolation that gives rise to them.

Translated by Karoline Kirst

By Anne-Bitt Gerecke