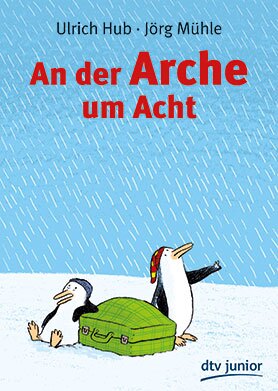

Ulrich HubJörg Mühle

An der Arche um Acht

[Be at the ark at eight]

- Patmos Verlag

- Düsseldorf 2007

- ISBN 978-3-7941-6109-6

- 63 Pages

- 5 Suitable for age 6 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Ulrich Hub

An der Arche um Acht

[Be at the ark at eight]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Portuguese: Brazil (2007 - 2008).

Sample translations

Review

It’s the same old story: the three penguins are bored, and so a quarrel starts. This time they’re squabbling about God, who allegedly isn’t very pleased that the littlest penguin wants to ‘do in’ a butterfly. But who is God? And how can anyone be sure He exists, given that He’s invisible? And what on earth was He thinking of when He created penguins? These are matters that the penguins simply can’t agree about. The only thing they’re certain of is that murdering a butterfly means that the littlest penguin can’t possibly get into Heaven. At this the littlest penguin stalks off in high dudgeon, whereupon something utterly unexpected occurs: a big fat pigeon brings the two remaining penguins a message direct from God, who is fed up with the eternal squabbling indulged in by man and beast alike, and has decided to save only two animal from each species from the mighty flood that is due to submerge the entire world. It just so happens that the two penguins are included amongst the chosen few, and the pigeon duly gives them their boarding cards for Noah’s Ark.

The penguins’ initial delight at being thus saved soon gives way to concern for their friend. Not wanting to leave him to a watery fate, they simply knock him unconscious, bundle him into a large suitcase, and smuggle him onto the ark. Amidst the general confusion the penguins manage at first to hide their stowaway from the suspicious pigeon. But their game is up once the pigeon hears a voice emanating from the suitcase, claiming to belong to God. All of a sudden, however, various things happen in rapid succession. The rain stops, the ark reaches land, and the animals can disembark — two by two. When the pigeon realises that she of all people has forgotten to bring a partner along with her, the penguins come to her rescue with a cunning ploy: the pigeon and the littlest penguin are able to leave the ark without raising Noah’s suspicions by disguising themselves as a happy couple on their way to the altar. Disparate though they are, the pair end up positively liking one another, and a liaison born of mere expediency turns into a genuine love match.

Despite their numerous squabbles, the obstinate animals in Ulrich Hub’s amusing tale are ultimately able to resolve all their problems by simply sticking together. Interestingly enough, however, the penguins’ differences of opinion reveal their remarkable similarity to God, for He too is ‘difficult to argue with’, He too ‘can’t be budged’ once He has ‘got an idea into his head.’

Thus none of the characters is completely free of flaws and character weaknesses, and even God is portrayed with deep ambivalence. Whilst the littlest penguin is initially afraid of a God that he perceives as stern and vengeful, he later projects a quite different image when he speaks to the exhausted pigeon from inside the suitcase. Without really having to think about it for any great length of time, he consoles her by promising that God will show understanding and assuring her that it’s perfectly alright to be cross with Him once in a while, and that He himself openly admits His own failings. He puts this all across so convincingly that even the other penguin believes for a brief moment that he has come face to face with God Himself.

Only the cruel carnage of the flood remains incomprehensible to the penguins to the very end. Even the conciliatory mood and the rainbow sent by God once they are safely back on dry land are insufficient to entirely convince them that such severe punishment was ever called for. God’s deepest secrets and designs thus remain inscrutable to them, and the animals find themselves once again dependent on mere conjecture as to God’s true nature.

By encouraging children to ask questions about God, yet without offering any quick and easy answers, Ulrich Hub leaves them plenty of scope for thought, whilst simultaneously showing that certain questions simply don’t have clear-cut answers. Children are not the only age-group who might readily identify with the animals, who are at once disrespectful yet naïve, deeply naughty yet conscience-stricken, and ever anxious to do the right thing. Thus for instance the littlest penguin, sceptical to the end, suggests that ‘Perhaps God doesn’t exist at all and it’s simply rained for an inordinately long period of time.’

The dry humour of this story is wonderfully complemented by Jörg Mühle’s mostly highly detailed and witty illustrations, which render the sometimes earthy, no-nonsense behaviour of the birds in particularly vivid terms. Just like Hub in his narrative, Mühle in his illustrations is unsparing in his depiction of the characters’ failings, foibles and emotions.

An der Arche um acht thus demonstrates on the one hand how important it is to think about God, whilst at the same time warning us not to lose sight of the bond we share with our fellow beings. That such a bond can be gladly accepted even in its strangest manifestations is demonstrated by the glorious love-relationship between the pigeon and the penguin that serves as the story’s romantic conclusion.

The penguins’ initial delight at being thus saved soon gives way to concern for their friend. Not wanting to leave him to a watery fate, they simply knock him unconscious, bundle him into a large suitcase, and smuggle him onto the ark. Amidst the general confusion the penguins manage at first to hide their stowaway from the suspicious pigeon. But their game is up once the pigeon hears a voice emanating from the suitcase, claiming to belong to God. All of a sudden, however, various things happen in rapid succession. The rain stops, the ark reaches land, and the animals can disembark — two by two. When the pigeon realises that she of all people has forgotten to bring a partner along with her, the penguins come to her rescue with a cunning ploy: the pigeon and the littlest penguin are able to leave the ark without raising Noah’s suspicions by disguising themselves as a happy couple on their way to the altar. Disparate though they are, the pair end up positively liking one another, and a liaison born of mere expediency turns into a genuine love match.

Despite their numerous squabbles, the obstinate animals in Ulrich Hub’s amusing tale are ultimately able to resolve all their problems by simply sticking together. Interestingly enough, however, the penguins’ differences of opinion reveal their remarkable similarity to God, for He too is ‘difficult to argue with’, He too ‘can’t be budged’ once He has ‘got an idea into his head.’

Thus none of the characters is completely free of flaws and character weaknesses, and even God is portrayed with deep ambivalence. Whilst the littlest penguin is initially afraid of a God that he perceives as stern and vengeful, he later projects a quite different image when he speaks to the exhausted pigeon from inside the suitcase. Without really having to think about it for any great length of time, he consoles her by promising that God will show understanding and assuring her that it’s perfectly alright to be cross with Him once in a while, and that He himself openly admits His own failings. He puts this all across so convincingly that even the other penguin believes for a brief moment that he has come face to face with God Himself.

Only the cruel carnage of the flood remains incomprehensible to the penguins to the very end. Even the conciliatory mood and the rainbow sent by God once they are safely back on dry land are insufficient to entirely convince them that such severe punishment was ever called for. God’s deepest secrets and designs thus remain inscrutable to them, and the animals find themselves once again dependent on mere conjecture as to God’s true nature.

By encouraging children to ask questions about God, yet without offering any quick and easy answers, Ulrich Hub leaves them plenty of scope for thought, whilst simultaneously showing that certain questions simply don’t have clear-cut answers. Children are not the only age-group who might readily identify with the animals, who are at once disrespectful yet naïve, deeply naughty yet conscience-stricken, and ever anxious to do the right thing. Thus for instance the littlest penguin, sceptical to the end, suggests that ‘Perhaps God doesn’t exist at all and it’s simply rained for an inordinately long period of time.’

The dry humour of this story is wonderfully complemented by Jörg Mühle’s mostly highly detailed and witty illustrations, which render the sometimes earthy, no-nonsense behaviour of the birds in particularly vivid terms. Just like Hub in his narrative, Mühle in his illustrations is unsparing in his depiction of the characters’ failings, foibles and emotions.

An der Arche um acht thus demonstrates on the one hand how important it is to think about God, whilst at the same time warning us not to lose sight of the bond we share with our fellow beings. That such a bond can be gladly accepted even in its strangest manifestations is demonstrated by the glorious love-relationship between the pigeon and the penguin that serves as the story’s romantic conclusion.

By Martina Schlögl