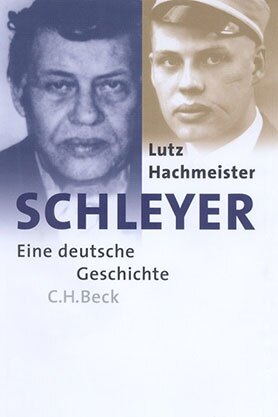

Lutz Hachmeister

Schleyer. Eine deutsche Geschichte

[Schleyer. A German Story]

- C.H.Beck Verlag

- Munich 2004

- ISBN 3-406-51863-X

- 447 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Lutz Hachmeister

Schleyer. Eine deutsche Geschichte

[Schleyer. A German Story]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Arabic I (2004 - 2005).

Sample translations

Review

As Lutz Hachmeister’s subtitle already indicates, this book is not a biography in the conventional sense. Schleyer. A German Story presents a longitudinal section of German history from 1915 to 1977. It sheds light on the areas of German society where the life of this representative of German industry primarily played out and which hold the explanations for his decisions and modus operandi. The author juxtaposes Schleyer’s personal biography with copious material pertaining to his social, politcal and economic environment.

In his introduction Hachmeister outlines the method with which he would like to shatter “the permanent occupation of Hanns Martin Schleyer’s biography by the Red Army Faction (RAF).“ By combining a biographical presentation of Schleyer’s family background, the course of his education, political involvement and career with a detailed examination of their social and political context, Hachmeister has opened an approach to an “understanding-based,” “empathetic” portrayal of Hanns Martin Schleyer’s life and world.

Even the way the author has structured the book places special emphasis on the first half of Schleyer’s life, thereby also underscoring Schleyer’s early involvement in political organizations and his wholesale adoption of the National Socialist world view, in addition to the strong influence of family factors. Hachmeister thus devotes two thirds of the biographical presentation (prior to Schleyer’s abduction in the fall of 1977) to the thirty years between 1915, the year of his birth, and 1945, when his employment in the economic office of Nazi-occupied Bohemia and Moravia ended with his flight and subsequent imprisonment by French occupation forces. The final third of the book spans another period of slightly more than thirty years and focuses equally on Schleyer’s rise at Daimler-Benz, his (lost) struggle for the chairmanship, and on his role as a representative of the German Employers’ Association within the political structures of a still-young Federal Republic of Germany during the 1960s and ‘70s.

Hanns Martin Schleyer was born into a family of theologians, lawyers and teachers during the middle of the First World War. Family sentiment was German nationalist. Even as a secondary school student, Schleyer had already become involved with a “fatherland-oriented” fraternity named Teutonia. In 1931 he joined the Hitler Youth and on July 1, 1933, two months after his 18th birthday, he became a member of the SS.

His years as a law student in Heidelberg also were defined by intense political commitments. After first playing an active role in his fraternity he soon concentrated exclusively on the key Nazi student groups, and in 1937 assumed various senior positions in the Nazi Studentenwerk (Student Association). At the same time he became a member of the National Socialist German Workers Party. Shortly after Hitler’s annexation of Austria in 1938, rather than taking a position as a legal trainee he moved to Innsbruck, where he headed the local Studentenwerk and received his degree in 1939.

He served in the Mountain Troops for just under a year until he was discharged as unfit, and then was posted as director of the Studentenwerk in Prague in 1941. Two years later he joined the Zentralverband der Industrie für Böhmen und Mähren (Central Federation of Industry for Bohemia and Moravia), first as a specialist and later as chief of staff for the president’s office where he remained employed until the end of the Second World War.

After fleeing from Prague he was imprisoned for three years in French-occupied southwestern Germany. Classified as a “fellow traveler” by the denazification authorities – not least because of false statements regarding his SS service rank – in 1949 he parlayed the expertise he had acquired during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia into a position at the foreign trade desk in the Baden-Baden Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Here he began his second career which would subsequently enable him to rise with exceptional speed to top positions at Daimler-Benz, including membership on the board of directors. In 1971, however, when he was unable to prevail against his competitor and influence the vote for the chairmanship in his favor, he increasingly stepped up his involvement with association work. Initially he became president of the Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Arbeitgeberverbände (BDA) (Confederation of German Employers' Associations) and then, in January 1977, he additionally assumed the presidency of the Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (BDI) (Federation of German Industries).

The author takes up Schleyer’s abduction by the RAF only in the final chapter, and he does not succumb to the danger of post facto relativism in this undertaking. Granted, the RAF loathed humankind, and in their thinking the abduction and murder of Hanns Martin Schleyer amounted to a logical escalation of their previous murders of federal attorney general Martin Buback and Deutsche Bank CEO Jürgen Ponto. Hachmeister, however, successfully renders the RAF’s line of reasoning understandable without concurrently minimizing their criminality. One of the book’s major achievements is the development of an understanding for the polarized and overall hysterical political climate during the “Deutscher Herbst” (German Autumn).

Detailed studies of individuals and deep insight into the life histories of a series of people who were, in some cases for decades, Schleyer’s key affiliates, friends and colleagues, make important contributions to this portrayal of “a man and his times.” Using the stations of Schleyer’s life Hachmeister presents a veritable panorama of the times. Numerous quotes by family members and colleagues not only throw Schleyer into greater relief as a person but also primarily convey an impression of the general atmosphere. The ultimate result is a composite, detailed picture which illuminates matters well beyond Schleyer as an individual. Schleyer’s exemplary career demonstrates the wide-spread and comparatively uninterrupted continuity of business management personnel during the transition from the Nazi dictatorship to the democratic system of the Federal Republic. Absent such linkage and without a contact network which also continued to function in the wake of 1945 his career would have been unthinkable.

The escalation of violence by commandos of the Red Army Faction is also considered, however, against the backdrop of personal statements by (former) members of the group. For Hachmeister’s many-voiced portrayal, the family origins and personal development lines of the individual RAF activists who participated in Schleyer’s abduction are just as important as the disclosures and reports originating in Schleyer’s surroundings. Using original texts dating from the time of the kidnappings as well as retrospective interviews with former RAF members, the author demonstrates equally the degree to which the activists lost touch with reality as well as the German government’s entanglement with the spiral of violence. That the events which climaxed in the fall of 1977 had a cathartic effect on the development of democracy in the Federal Republic of Germany constitutes the second central tenet of this suspensefully written and carefully researched book.

Thus, Schleyer. A German Story represents far more than the biography of an individual who at the end of his life became the tragic victim of a blind fanaticism which remained unchecked by the prevailing raison d’etat. Lutz Hachmeister’s book on Hanns Martin Schleyer and his times makes an important contribution to our understanding of the Federal Republic as we know it today.

In his introduction Hachmeister outlines the method with which he would like to shatter “the permanent occupation of Hanns Martin Schleyer’s biography by the Red Army Faction (RAF).“ By combining a biographical presentation of Schleyer’s family background, the course of his education, political involvement and career with a detailed examination of their social and political context, Hachmeister has opened an approach to an “understanding-based,” “empathetic” portrayal of Hanns Martin Schleyer’s life and world.

Even the way the author has structured the book places special emphasis on the first half of Schleyer’s life, thereby also underscoring Schleyer’s early involvement in political organizations and his wholesale adoption of the National Socialist world view, in addition to the strong influence of family factors. Hachmeister thus devotes two thirds of the biographical presentation (prior to Schleyer’s abduction in the fall of 1977) to the thirty years between 1915, the year of his birth, and 1945, when his employment in the economic office of Nazi-occupied Bohemia and Moravia ended with his flight and subsequent imprisonment by French occupation forces. The final third of the book spans another period of slightly more than thirty years and focuses equally on Schleyer’s rise at Daimler-Benz, his (lost) struggle for the chairmanship, and on his role as a representative of the German Employers’ Association within the political structures of a still-young Federal Republic of Germany during the 1960s and ‘70s.

Hanns Martin Schleyer was born into a family of theologians, lawyers and teachers during the middle of the First World War. Family sentiment was German nationalist. Even as a secondary school student, Schleyer had already become involved with a “fatherland-oriented” fraternity named Teutonia. In 1931 he joined the Hitler Youth and on July 1, 1933, two months after his 18th birthday, he became a member of the SS.

His years as a law student in Heidelberg also were defined by intense political commitments. After first playing an active role in his fraternity he soon concentrated exclusively on the key Nazi student groups, and in 1937 assumed various senior positions in the Nazi Studentenwerk (Student Association). At the same time he became a member of the National Socialist German Workers Party. Shortly after Hitler’s annexation of Austria in 1938, rather than taking a position as a legal trainee he moved to Innsbruck, where he headed the local Studentenwerk and received his degree in 1939.

He served in the Mountain Troops for just under a year until he was discharged as unfit, and then was posted as director of the Studentenwerk in Prague in 1941. Two years later he joined the Zentralverband der Industrie für Böhmen und Mähren (Central Federation of Industry for Bohemia and Moravia), first as a specialist and later as chief of staff for the president’s office where he remained employed until the end of the Second World War.

After fleeing from Prague he was imprisoned for three years in French-occupied southwestern Germany. Classified as a “fellow traveler” by the denazification authorities – not least because of false statements regarding his SS service rank – in 1949 he parlayed the expertise he had acquired during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia into a position at the foreign trade desk in the Baden-Baden Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Here he began his second career which would subsequently enable him to rise with exceptional speed to top positions at Daimler-Benz, including membership on the board of directors. In 1971, however, when he was unable to prevail against his competitor and influence the vote for the chairmanship in his favor, he increasingly stepped up his involvement with association work. Initially he became president of the Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Arbeitgeberverbände (BDA) (Confederation of German Employers' Associations) and then, in January 1977, he additionally assumed the presidency of the Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (BDI) (Federation of German Industries).

The author takes up Schleyer’s abduction by the RAF only in the final chapter, and he does not succumb to the danger of post facto relativism in this undertaking. Granted, the RAF loathed humankind, and in their thinking the abduction and murder of Hanns Martin Schleyer amounted to a logical escalation of their previous murders of federal attorney general Martin Buback and Deutsche Bank CEO Jürgen Ponto. Hachmeister, however, successfully renders the RAF’s line of reasoning understandable without concurrently minimizing their criminality. One of the book’s major achievements is the development of an understanding for the polarized and overall hysterical political climate during the “Deutscher Herbst” (German Autumn).

Detailed studies of individuals and deep insight into the life histories of a series of people who were, in some cases for decades, Schleyer’s key affiliates, friends and colleagues, make important contributions to this portrayal of “a man and his times.” Using the stations of Schleyer’s life Hachmeister presents a veritable panorama of the times. Numerous quotes by family members and colleagues not only throw Schleyer into greater relief as a person but also primarily convey an impression of the general atmosphere. The ultimate result is a composite, detailed picture which illuminates matters well beyond Schleyer as an individual. Schleyer’s exemplary career demonstrates the wide-spread and comparatively uninterrupted continuity of business management personnel during the transition from the Nazi dictatorship to the democratic system of the Federal Republic. Absent such linkage and without a contact network which also continued to function in the wake of 1945 his career would have been unthinkable.

The escalation of violence by commandos of the Red Army Faction is also considered, however, against the backdrop of personal statements by (former) members of the group. For Hachmeister’s many-voiced portrayal, the family origins and personal development lines of the individual RAF activists who participated in Schleyer’s abduction are just as important as the disclosures and reports originating in Schleyer’s surroundings. Using original texts dating from the time of the kidnappings as well as retrospective interviews with former RAF members, the author demonstrates equally the degree to which the activists lost touch with reality as well as the German government’s entanglement with the spiral of violence. That the events which climaxed in the fall of 1977 had a cathartic effect on the development of democracy in the Federal Republic of Germany constitutes the second central tenet of this suspensefully written and carefully researched book.

Thus, Schleyer. A German Story represents far more than the biography of an individual who at the end of his life became the tragic victim of a blind fanaticism which remained unchecked by the prevailing raison d’etat. Lutz Hachmeister’s book on Hanns Martin Schleyer and his times makes an important contribution to our understanding of the Federal Republic as we know it today.

Translated by Philip Schmitz

By Heike Friesel