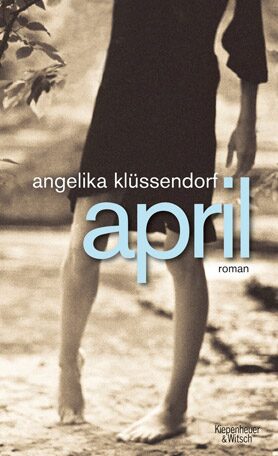

Angelika Klüssendorf

April

[April]

- Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag

- Cologne 2014

- ISBN 978-3-462-04614-4

- 224 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Angelika Klüssendorf

April

[April]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Russian (2012 - 2014).

Sample translations

Review

In her last novel she was called, “The Girl”, now she has given herself the English-sounding name “April.” And if it seems as though she is yearning for America, dreaming of freedom and experiencing a spring awakening, it is no coincidence: The author Angelika Klüssendorf, who grew up in Leipzig before the fall of the Wall, has created a protagonist largely based on her own life—in fact, this is the second novel dedicated to her autobiographical heroine: a young girl, who doggedly strives to free herself from the dreary confines of her GDR youth and live a life of self-determination and worldly sophistication.

If “The Girl” tells the story of an adolescent from a broken home, going through puberty in the seventies; “April” is told against the backdrop of the political upheavals of the eighties and details the protagonist’s attempt to create an independent life after she has come of age and been released from a youth services center. The novel follows her through the various stations of her education until she gradually finds her place in life, even if in the end she does not necessarily find true happiness.

It takes an exceptional amount of energy and strength for her to achieve her goals, because the young woman’s spirit has been crushed by a dysfunctional childhood caused by an irresponsible mother and an alcoholic father. Her April weather, manic-depressive symptoms, her inability to deal with human ties, cannot be surmounted by getting married or becoming a mother, nor does discovering her literary talent help. Nonetheless, Angelika Klüssendorf has not written a psycho-drama, instead she has created a starkly laconic coming-of-age novel that sheds light on a recent period of German history. Without pathos or reproach, without reducing the problems of the individual to social conditions, the author elegantly manages to expose how these forces relate. Good things also happen to the tough, yet vulnerable heroine. After she is fired from her job at the “Electrical Power Plant Leipzig-Halle,” she is sent to a mental hospital, where she is assigned a therapeutic museum job; her unfriendly landlady ultimately proves to have a good sense of humor, and Hans, the father of her son, is her patient and caring, though often perplexed, partner. But there are other men in her life as well; she joins a clique that discusses art and politics and gets inspired by literature and music: in East Germany people listened to Gustav Mahler just as people in the West read Bulgakov's, “The Master and Margarita.”

Prior to the fall of the Wall, April participates in a candlelight protest which was considered inimical to the socialist system, and is forced to emigrate with her family to a capitalist country that she had always imagined “as a kind of Ice Palace…like in the fairy tale, ‘Snow Queen….the streets, sidewalks, walls of houses lined in tile, even during the summer frost and durable as marble. Perfumed people without a scent of their own.” Strangely, the image leaves a lasting impression, and one can’t help but think of it today when traveling from the former East back to the West. Angelika Klüssendorf’s spare, incisive language makes even the mundane details of everyday life memorable.

Once the heroine realizes her calling as a writer, we cannot help but view her as the narrator of her own story. It is in the nature of the fictional character that a part of her remains aloof, despite all the opened borders and all of her journeys, nothing can change that. She does, however, learn a great deal about herself and her problems, and in the end she might even have the possibility of reconciling herself to her difficult childhood. May has arrived.

If “The Girl” tells the story of an adolescent from a broken home, going through puberty in the seventies; “April” is told against the backdrop of the political upheavals of the eighties and details the protagonist’s attempt to create an independent life after she has come of age and been released from a youth services center. The novel follows her through the various stations of her education until she gradually finds her place in life, even if in the end she does not necessarily find true happiness.

It takes an exceptional amount of energy and strength for her to achieve her goals, because the young woman’s spirit has been crushed by a dysfunctional childhood caused by an irresponsible mother and an alcoholic father. Her April weather, manic-depressive symptoms, her inability to deal with human ties, cannot be surmounted by getting married or becoming a mother, nor does discovering her literary talent help. Nonetheless, Angelika Klüssendorf has not written a psycho-drama, instead she has created a starkly laconic coming-of-age novel that sheds light on a recent period of German history. Without pathos or reproach, without reducing the problems of the individual to social conditions, the author elegantly manages to expose how these forces relate. Good things also happen to the tough, yet vulnerable heroine. After she is fired from her job at the “Electrical Power Plant Leipzig-Halle,” she is sent to a mental hospital, where she is assigned a therapeutic museum job; her unfriendly landlady ultimately proves to have a good sense of humor, and Hans, the father of her son, is her patient and caring, though often perplexed, partner. But there are other men in her life as well; she joins a clique that discusses art and politics and gets inspired by literature and music: in East Germany people listened to Gustav Mahler just as people in the West read Bulgakov's, “The Master and Margarita.”

Prior to the fall of the Wall, April participates in a candlelight protest which was considered inimical to the socialist system, and is forced to emigrate with her family to a capitalist country that she had always imagined “as a kind of Ice Palace…like in the fairy tale, ‘Snow Queen….the streets, sidewalks, walls of houses lined in tile, even during the summer frost and durable as marble. Perfumed people without a scent of their own.” Strangely, the image leaves a lasting impression, and one can’t help but think of it today when traveling from the former East back to the West. Angelika Klüssendorf’s spare, incisive language makes even the mundane details of everyday life memorable.

Once the heroine realizes her calling as a writer, we cannot help but view her as the narrator of her own story. It is in the nature of the fictional character that a part of her remains aloof, despite all the opened borders and all of her journeys, nothing can change that. She does, however, learn a great deal about herself and her problems, and in the end she might even have the possibility of reconciling herself to her difficult childhood. May has arrived.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

By Kristina Maidt-Zinke

Kristina Maidt-Zinke is a book and music critic at the Süddeutsche Zeitung and also writes reviews for Die Zeit.